|

|

|

CASE REPORT / CAS CLINIQUE

CERVICAL INTRADURAL AND EXTRAMEDULLARY EPIDERMOID CYST: A RARE CAUSE OF CERVICAL SPINE COMPRESSION- A CASE REPORT

KYSTE ÉPIDERMOÏDE CERVICAL INTRADURAL EXTRAMÉDULAIRE : UNE CAUSE RARE DE COMPRESSION MEDULLAIRE CERVICALE

E-Mail Contact - HAIDARA Aderehime :

adermedic@gmail.com

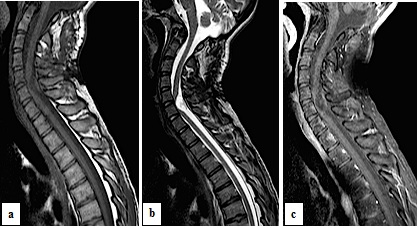

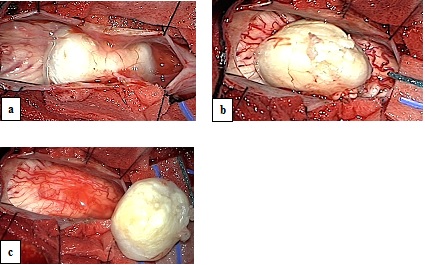

ABSTRACT Background: Epidermoid cysts of the central nervous system are benign congenital tumors resulting from the abnormal inclusion of ectodermal tissues during the neural tube closure. Although intracranial location is commonly observed, spinal epidermoid cysts are rare representing 1% of adult spinal cord tumors. Case report: Herein, we report the case of a cervical intradural extramedullary epidermoid cyst in a 22-years-old male with previous history of cerebellar astrocytoma. The cyst was surgically removed with favorable outcome. Conclusion: Furthermore, we discussed the clinical, radiological and therapeutic aspects of an unusual location of epidermoid cyst. Keywords: epidermoid cyst, intraspinal, magnetic resonance imaging RÉSUMÉ Introduction : Les kystes épidermoïdes du système nerveux central sont des lésions bénignes d’origine congénitale, résultant de l’inclusion anormale de tissus ectodermiques lors de la fermeture du tube neural. Bien que la localisation intracrânienne soit inhabituelle, les kystes épidermoïdes rachidiens sont rares et représentent 1% des tumeurs de la moelle épinière chez l’adulte. Cas clinique : Nous rapportons ici le cas d’un kyste épidermoïde extramédullaire intradural cervical chez un homme de 22 ans ayant des antécédents d’astrocytome cérébelleux opéré quelques années auparavant. Le kyste a été enlevé chirurgicalement avec un résultat favorable. Conclusion : Nous avons discuté à travers une revue de littérature, les aspects cliniques, radiologiques et thérapeutiques d’un emplacement inhabituel du kyste épidermoïde. Mots-clés : imagerie par résonance magnétique, intrarachidien, kyste épidermoïde. INTRODUCTION Epidermoid cysts (EC) are rare benign neoplasms which account for less than 1% of all adult intraspinal tumors (6,10). They are congenital condition due to an abnormal implantation of epidermal cells during neural tube closure (2,13,14,18). However, EC can be acquired in patients who had previous lumbar puncture, spinal trauma or surgery (8,9,12,20,24,25,26). Moreover, EC can be extra/intra dural or extra /intra medullary (6,7,15,27). When located in the spine, EC commonly occurs at the lumbosacral region. Therefore, cervical and thoracic spinal cord locations are rare (1,2,4,12,14,17,19). Clinically, spinal EC leads to an insidious onset of spinal cord compression in which the severity is correlated with the cyst size and location (2,7,10,19). Spinal MRI is the imaging study of choice in the diagnosis as it shows an iso/hypo-intense image in T1-weighted (T1W) and an hyperintense image in T2-weighted (2,13,15,16,21). The treatment of epidermoid cysts is essentially surgical, and when possible, complete removal must be the goal because of the recurrence risk (17,27). CASE A 22-year-old male presented with a 5 months’ history of gradual gait disorders and right sided weakness. He had a history of a posterior fossa surgery 5 years ago for a cerebellar astrocytoma. This had left him with cerebellar sequelae syndrome. His clinical examination showed a cervical spinal cord compression syndrome with right hemiparesis grade 3/5, hyperreflexia, and bilateral Babinski sign. An occipito-cervical scar related to his previous surgery was noticed upon skin examination. The MRI of the cervical spine revealed a well-defined intradural extramedullary lesion extending from C5 to C6 level and markedly compressing the cord. The lesion was hypointense on T1W images, hyperintense on T2W with no enhancement after contrast injection suggesting at first a spinal arachnoïd cyst. The brain MRI, requested in relation to the history of cerebellar astrocytoma, was normal except for the cavity left by the previous tumor resection (Figure 1). The patient underwent surgery. A laminectomy was performed from C3 to C7. After opening the dura, we identified a well-encapsulated tumor mass (Figure 2). The lesion was oval, pearly white, soft with a cleavage plane allowing easy removal at once without damaging the spinal cord tissue. The histopathology exam showed a squamous epithelium, stratified, keratinized, with desquamated epithelial cells rich in keratin and cholesterol consistent with an epidermoid cyst. The postoperative outcome was good with complete motor recovery after physiotherapy. Control MRI of the cervical spine at 6 and 12 months did not show any recurrence. DISCUSSION Epidermoid cyst (EC), also called “pearly tumor” has been described for the first time in 1835 by Cruveilhier (6). The intraspinal location of the epidermoid cysts account for less than 1% of all intraspinal tumors in adults and are mostly intradural extramedullary (6,7,10,15,25,27). Their origin can be congenital or acquired. The congenital form takes its origin from anomalous inclusion of the ectoderm tissue during the closure of the neural tube in early fetal life and possibly may be associated with a defective closure of the dural tube (2,13,14,18). Acquired epidermoid cysts usually occur years after iatrogenic penetration of the skin fragments due to trauma including lumbar spinal punctures (2,4,12,14,17,19). Reports of this ectopic ectodermal migrating to sites more rostral have also been reported (1,3,16). EC commonly occurs at the lumbosacral region. Therefore, cervical and thoracic spinal cord locations are rare (1,2,4,12,14,17,19). In our clinical case, the localization was cervical intradural extramedullary. Indeed cervical localizations reported in the literature would be related to an extension of the cyst from an intracranial starting point, most often in the posterior cerebral fossa (1,16). It should be noted that our patient was operated on for 5 years for a cerebellar astrocytoma. The clinical picture is generally progressive medullary compression whose severity is a function of the size and the location of the lesion. Acute forms have been reported and may be due to rupture of cyst contents resulting in chemical meningitis (1,3,16). MRI is the gold standard for the radiological diagnosis of the epidermoid cyst (13,15). The lesion appears, as in our case, most often in a typical homogeneous or heterogeneous hypointense signal on a T1-weighted image and a hyperintense signal on a T-weighted image. No enhancement is observed in most cases after injection of contrast products. However, atypical signal intensity variations have been reported in epidermoid tumors. The lesion can appear as a hyperintense signal on a T1-weighted image and a hypo-intense signal on a T2-weighted image (2,13,15,16,21). This variability of the signal makes the preoperative diagnosis difficult and could be related to the chemical state of cholesterol or the relative composition of cholesterol and keratin (5). When the differential diagnosis arises with an epidermoid cyst, the diffusion sequences make it possible to make the difference. The epidermoid cyst has a heterogeneous appearance on the FLAIR sequence, with a high signal on the diffusion and restriction sequence on the ADC map. Celik (5) reported an unusual case of intra-spinal epidermoid cyst associated with an arachnoid cyst in the same patient where the diffusion sequences were useful to differentiate the two lesions. The treatment of the intraspinal epidermoid cyst is essentially surgical (2,6,12,27). The removal can be easy and complete, as in our case, with a cleavable arachnoidal plane between the capsule of the lesion and the medullary tissue (27). The lesion appears most often macroscopically rounded, pearly white color, firm consistency, encapsulated in monobloc and non-haemorrhagic. However, total excision may not always be possible when the tumor is strongly adherent making the procedure dangerous with a risk of neural damage (10). In the case of partial resection, rigorous postoperative monitoring of the residual tumor is required because recurrences, between 10 and 30%, have been reported in the literature (8,27). Radiotherapy is not established in the treatment of EC; it should be considered as an alternative to palliative surgery and in patients who cannot undergo surgery (3). CONCLUSIONS The intraspinal epidermoid cyst is a rare disease which pathogenesis is not clearly elucidated. Its prognosis is generously favorable. The intraspinal epidermoid cyst must be considered in spinal cord compression with a hyperintense image in T1 and hypertense in T2 on the MRI. Total excision with microsurgical technic may lead to complete recovery for patients with symptomatic lesions.

Figure 1 (a) Sagittal T1-weighted image shows hypointense mass, extending from C5 to C6. (b) On the T2-weighted image the tumor mass is hyperintense and heterogeneous. (c) No enhancement of the lesion after contrast administration.

Figure 2 : (a) Subarachnoid encapsulated oval mass after opening the dura. (b) Pearl white color appears with a cleavable arachnoidal plane. (c) Complete excision of the lesion without neural tissue damage. REFERENCES

|

© 2002-2018 African Journal of Neurological Sciences.

All rights reserved. Terms of use.

Tous droits réservés. Termes d'Utilisation.

ISSN: 1992-2647