CLINICAL STUDIES / ETUDES CLINIQUES

PERSISTENT MISSED DIAGNOSIS OF ADULT CHIARI 1 MALFORMATION IN A DEVELOPING COUNTRY: A NEUROSURGICAL CASE SERIES

DIAGNOSTICS OMIS CHEZ DES ADULTES ATTEINTS DE MALFORMATION DE TYPE CHIARI 1 DANS UN PAYS EN VOIE DE DEVELOPPEMENT : UNE SERIE NEUROCHIRURGICALE

- Division of Neurological Surgery, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, and University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

- Service de Neurochirurgie, Hôpital d’Instruction des Armées (HIA), Clinique Universitaire de traumatologie Orthopédie et de Chirurgie Réparatrice (CNHU HKM), Cotonou, République du Benin

- Department of Radiology, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, and University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

ABSTRACT

Background

In advanced countries of the world, increasing high clinical index of suspicion, and especially widespread availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have both made adult Chiari I malformation no longer as clinically elusive as in the past. The situation is however different in the developing countries where due to diverse reasons the condition is still rarely diagnosed. Here we present a series of 3 cases of previously missed diagnosis managed in our service

Patients/Methods

A prospective descriptive series of cases of adult Chiari 1 seen over a 30-month period in a developing African country.

Results

The three cases were: i) A 44-year-old highly-skilled professional with thoracic scoliosis from childhood. He presented with a 9-year history of new onset clumsiness of hands, weak hand grip, C4 spastic quadriparesis and C5 sensory level. ii) A 32-year-old woman, another highly skilled professional, with progressive C4 spastic quadriparesis and C2 sensory level; and iii) A 32-year-old man with ataxia, right lower limb weakness (1-year after a sub-optimally treated traumatic femoral head fracture), wasting of the hand muscles and cerebellar signs. Clinical diagnosis was missed by the referring physicians in each case. Cranio-cervical MRI in all 3 revealed Chiari 1 posterior fossa anomaly and extensive spinal cord syrinx of varying extents. Two of the cases were treated surgically in our facility with fair results whilst the third case elected to seek surgical treatment abroad.

Conclusions

There is a need to increase awareness of the occurrence of adult Chiari 1 malformation in Nigeria to prevent continued mis-diagnosis and mis-management of this very debilitating but treatable condition

Keywords: Chiari, developing country, missed diagnosis, MRI, Nigeria

RESUME

Contexte

Dans les pays développés, de nombreux critères cliniques de présomption ainsi que la vulgarisation particulière de l’imagerie par résonance magnétique (MRI), permettent aujourd’hui, contrairement aux seuls arguments cliniques utilisés dans le passé, de disposer d’arguments diagnostiques divers dans la malformation de Chiari I chez l’adulte.

La situation est cependant différente dans les pays en voie de développement où, en raison des raisons diverses, cette affection est rarement diagnostiquée. Nous rapportons ici une série de 3 cas initialement non diagnostiqués et suivis dans le service.

Patients et méthodes

Il s’agit d’une étude descriptive de patients adultes présentant une malformation de Chiari I pris en charge pendant plus de 30 mois dans un pays d’Afrique subsaharien.

Résultats

Trois cas avaient été colliges. Le premier était un ouvrier qualifié de 44 ans avec une scoliose thoracique remontant à l’enfance. Il a consulté pour des troubles inauguraux de la main datant de 9 ans, associant une impotence fonctionnelle du poignet et une quadri parésie spastique du territoire C4 avec un niveau sensitif remontant à C5. Dans le deuxième cas, il s’agissait aussi d’un ouvrier, âgé de 32 ans avec une quadri parésie spasmodique d’installation progressive en C4 et un niveau sensitif C2. Le dernier patient âgé de 32 ans, présentait une symptomatologie cérébelleuse dont une ataxie, une amyotrophie de la main et une faiblesse musculaire du membre inferieur droit remontant à 1 an développée aux décours d’une fracture négligée de la tête fémorale.

Dans aucun cas, le diagnostic clinique n’avait été suspecté par les médecins référant. Les explorations d’IRM cranio-vertébrales réalisées dans notre service avaient révélé des anomalies de la fosse postérieure typiques d’une malformation de Chiari I ainsi que des syrinx médullaires extensifs, aux limites variées. Deux patients avaient été opérés dans notre service avec des résultats encourageants tandis que le troisième avait choisi de se faire soigner à l’étranger.

Conclusion

Au Nigeria, il existe un réel besoin de sensibilisation sur l’existence de la malformation de Chiari I de l’adulte, afin de limiter les retards diagnostiques et les difficultés de prise en charge d’une pathologie très handicapante mais de traitement facile.

Mots-clés : Chiari, diagnostic, IRM, Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

The Chiari I malformation is an anomaly in which there is caudal herniation of the cerebellar tonsils beyond the limit of 5 mm below the foramen magnum.(4) It is usually also associated with syrinx in the spinal cord, and rarely with hydrocephalus.(2, 10) It is the first of the four complex congenital anomalies of the hindbrain in the posterior cranial fossa that were first elucidated by the trio of Cleland, Chiari and Arnold in the closing decade of the 19th century.(1,4, 7) These malformations were and are essentially childhood diseases. But it later became known that some cases of the type I variant might come to clinical attention only in adolescence and adulthood.(1, 4)

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has so simplified the evaluation of clinically suspected cases of adult Chiari I that its diagnosis is now made with confidence ante-mortem, and not only post-mortem or intra-operatively as it was in the past.(2,4,7) This is especially so in the practice environments of many developed countries where the clinical awareness is high and MRI is readily available.

The situation, in contrast, is still not so in low-resource practice settings like ours in Nigeria, a developing country in Africa. Hence the literature on the ante-mortem management of adult Chiari I in sub-Saharan Africa is very scanty. (9, 12,15) This paper presents our experience with the clinical management of three consecutive cases of adult Chiari I malformation in a Nigerian neurosurgical service. All the three cases were initially unrecognized by their respective referring physicians, causing delay in prompt and effective management.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Clinical case 1

A 44-year-old man, a very productive professional, was referred to neurosurgery for the first time in adulthood. His complaint was a 9-year history of clumsiness and difficulty with writing with his right hand. He had developed a thoracic spine scoliosis of insidious onset since his childhood which apart from the cosmetic embarrassment had not in any way limited his functional and physical activities. Nine years before our review he noticed progressive clumsiness of the left upper limb and paraesthesia of the left hand. He also had episodic numbness over the left shoulder radiating down the forearm.

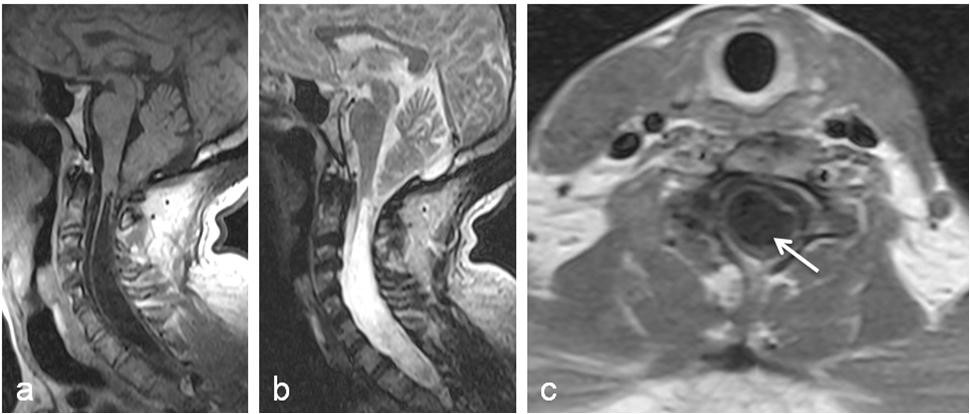

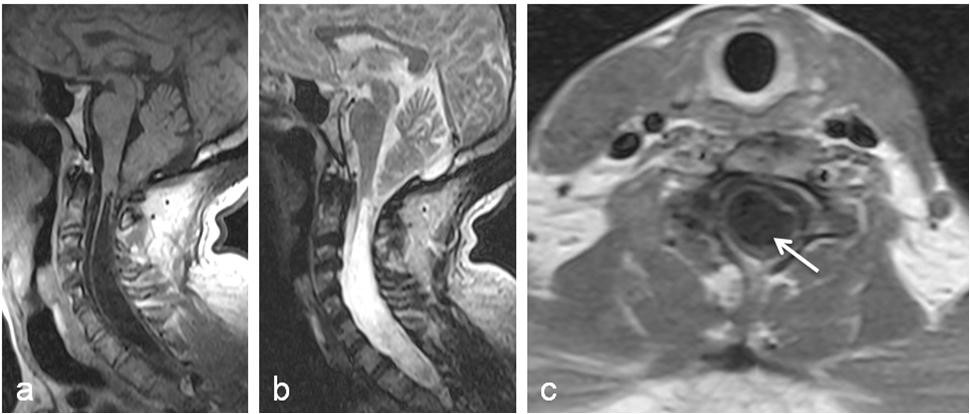

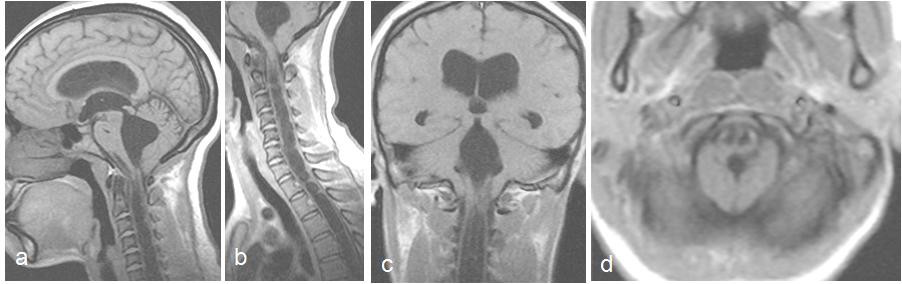

Neurological examination revealed GCS of 15. There was no meningism or gross cranial nerve deficit. He had a marked left lateral non-tender thoracic scoliosis; C3 hyper-reflexic quadriparesis worse in the upper limbs with Babinski but negative Hoffman’s sign; a 10-degree fixed flexion deformity of the right elbow, some clawing of the fingers of both hands, and wasting of the intrinsic muscles of the hands bilaterally. The grip power was 4/5 bilaterally. He had a sensory level of C5 bilaterally to all cutaneous sensory modalities: touch, pain, temperature. The vibration and joint position senses were depressed bilaterally from the upper extremities and distally. We made a clinical diagnosis of complex spinal deformity with possible high cervical canal stenosis and syrinx. Cervical MRI showed a small-size posterior fossa that is shallow with high-rising tentorium. There was some caudal stretching of the medulla oblongata, and the cerebellar tonsil projected down below the level of foramen magnum, figure 1. In addition, there was associated syringomyelia of the cervico-thoracic cord. Plain X-ray imaging of the other spinal levels revealed only the features of thoraco-lumbar scoliosis. Clinical examination of the other systems of the body revealed no other abnormalities.

The patient elected to have the surgical treatment of this Chiari 1 anomaly done overseas. He has since returned to us for postoperative follow-up care. He remains functionally independent 6 years post op.

Clinical case 2

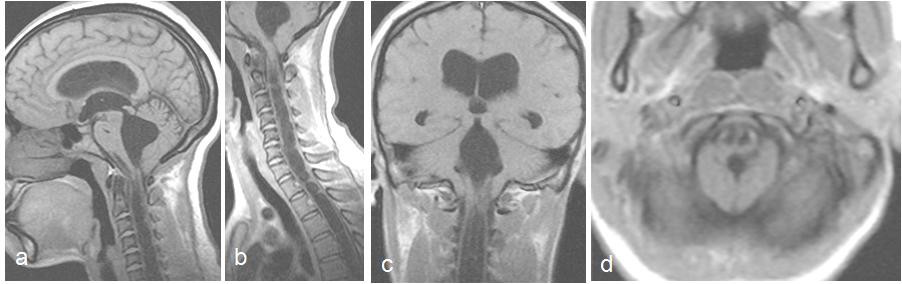

A 32-year-old female, another highly-skilled professional, presented with a history of progressive rotatory quadriparesis, gait deficits, numbness of both upper extremities and hoarseness of the voice all of about 9 months duration. Clinical examination showed a young lady with C4 spastic quadriparesis worse in the upper limbs, right-sided V2, V3 hypoaesthesia and C2 sensory level. A craniocervical MRI study showed Chiari 1 changes in the posterior fossa, figure 2. There was associated syringomyelia of the cervical spinal cord. She was offered suboccipital craniectomy and C1 laminectomy, cervicomedullary durotomy and fascia lata expansile duraplasty; she responded well to this surgical decompression. She is stable neurologically, has independent ambulation, and is still being followed up. As at the last review, she had made some gains in motor power, now ambulating with minimal support; the voice was better, but she remained spastic.

Clinical case 3

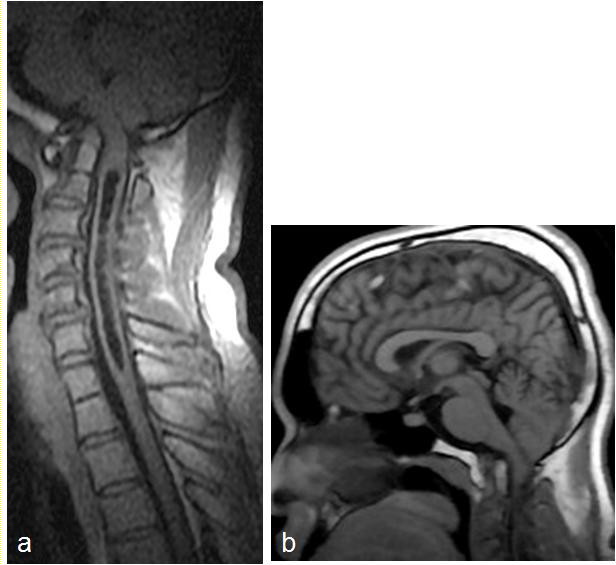

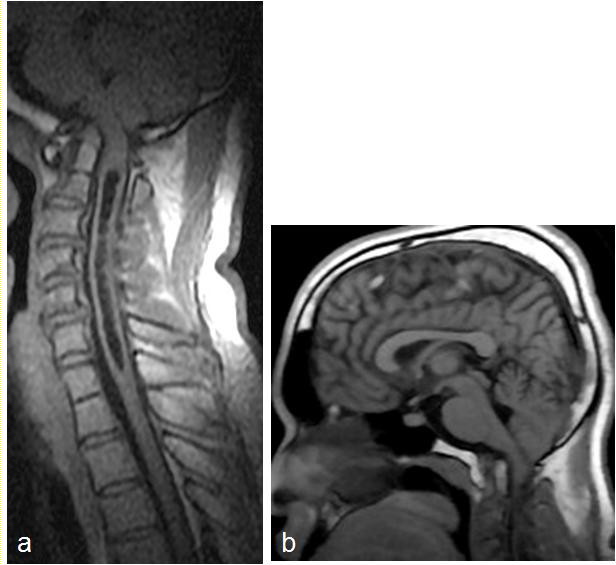

Another 32-year-old professional man had been on prolonged hospital admission of about a year long for a posttraumatic right femoral neck fracture. He developed headache and gait ataxia of about 3months’ duration. Examination revealed a young man with gait impairment, wasting of the intrinsic muscles of the hands, right lower limb monoparesis and global hyper-reflexia. There was also right VII palsy, bilateral nystagmus, and right sided dysmetria. A cranio-cervical MRI study showed tonsilar herniation and syrinx involving the medulla and the cervico-thoracic spinal cord, figure 3. He successfully underwent surgical decompression of the posterior fossa, that is, suboccipital craniectomy and C1 laminectomy. He had uneventful postoperative course, was discharged home in stable neurological condition, but has since been lost to follow up.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective consecutive case series we present some interesting aspects of the surgical neurology of the problem of adult Chiari 1 malformation in an African resource-limited practice. Firstly there is the issue of the apparent non-awareness of this disease condition among other health workers in our practice area.(15) Hence the mis-diagnosis and mis-management of 3 such cases in these otherwise financially capable young African professionals. In one case, a skilled professional lived for 44 years since childhood with the disease before diagnosis was made.

The clinical presentation of Chiari I beyond childhood is highly varied. Therefore earlier reports on adult Chiari I were mainly as postmortem findings (1, 15). Nevertheless, the clinical symptomatology of adult Chiari I have some fairly well defined patterns. One is headache that is mainly occipital, and may be associated with some tenderness or stiffness’ in the occipital and upper cervical region. There may be other clinical symptoms of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) from associated hydrocephalus- vomiting, visual obscurations and cognitive impairment. (1, 4, 11) Another pattern is from brainstem and lower cranial nerve deficits and include dizziness, vertigo, facial pain simulating trigeminal neuralgia, and even symptoms and signs of bulbar palsy.(1, 4, 18). Yet another pattern is that of cerebellar deficit including ataxia, nystagmus and general loss of limb coordination. Sensory loss may present as loss of joint position sense and vibration distally. And syringomyelic syndrome is evident by dysaesthetic pain and discomfort in the cape region of the shoulder and upper limbs, and muscle wasting in the different myotomal groups of the upper limbs. (1, 4) It also sometimes present with progressive quadriparesis, upper motor neuron type, and wasting in the intrinsic muscles of the hand. What is more, autonomic dysfunction may also present as dyshidrosis, sphinteric dysfunction, and loss of sexual functions. (18) These symptom complex were used to make clinical diagnosis of many cases in the pre-MRI era.

Although the advent of computerized neuroradiological imaging studies, particularly MRI, has made its ante-mortem diagnosis much easier in the current clinical practice era, adult Chiari I malformation still remains such a great clinical mimicker of other diverse disease conditions.(1, 2, 8, 14, 18) Some of these include dysphagia(5, 6); benign paroxysmal positional vertigo(17); demyelinating / degenerative diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS) and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)(6, 13, 18); craniovertebral junction skeletal developmental anomalies(3, 4, 9); lower cranial nerve neuropathies, and posterior cranial fossa tumours of the brainstem, cerebellum, and the foramen magnum.(1, 7, 18) This fact therefore underscores the critical importance of obtaining MRI study of the craniovertebral region in clinical cases with ill-defined neurological symptoms referable to that part of the neuraxis. But even this fact might only be a theoretical one in low-resource practice areas like our own.

More importantly however may be the issue of the still-very-poor accessibility to MRI study that is obtainable in our particular privately funded health system.(9, 12, 15) The MRI facilities, firstly, are not yet widely available. They are also not so easily affordable to the patient population in our pay-for-service health care. Still, the few available facilities are not always accessible. Sometimes this is simply from constant equipment down times from lack of appropriate maintenance. Mwang’ombe and Kiroko reported an observational of study of 38 cases, age 10 -49 years, of craniovertebral juntion abnormalities requiring neurosurgical attention in Kenya, in the year 2000. (9) None of them had the benefit of MRI evaluation, probably due to non-availability of this essential diagnostic study. Five of these cases were said to have Arnold-Chiari’ malformation. It is however not certain whether these were indeed Chiari I malformation or Chiari II, which are a somewhat different disease entity, and are the ones technically referred to as Arnold-Chiari malformation’ (1, 4) In essence, in-hospital diagnosis of Chiari I in the era before MRI was made only on the clinical symptomatology earlier addressed in this discussion.(1,9)

All the foregoing in effect may be why reports of this clinical neurological condition are very scanty indeed from our region.(15) And this very small cohort of cases that we report may thus, ironically, be the largest’ to date on the correct eventual ante-mortem diagnosis, surgical treatment, and postsurgical follow-up of a series of adult Chiari I malformation in sub-Saharan Africa. A case of Arnold Chiari malformation complicated by Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease following surgical repair was reported from South Africa earlier.(16) It is hoped, therefore, that this report would further help call the attention of our colleagues in this region to the critical importance of carefully performing accurate neurological clinical evaluation, and, appropriate neuroradiological examination, MRI, in the diagnostic elucidation of unexplained clinical symptomatology referable to the upper cervical spine and or the craniovertebral junction. (18)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

REFERENCES

- BANERJI NK, MILLAR JH. Chiari malformation presenting in adult life. Its relationship to syringomyelia. Brain 1974; 97: 157-68.

- BARKOVICH A, WIPPOLD F, SHERMAN J, CITRIN C. Significance of cerebellar tonsillar position on MR. American journal of neuroradiology 1986; 7: 795-9.

- BROCKMEYER D, GOLLOGLY S, SMITH JT. Scoliosis associated with Chiari 1 malformations: the effect of suboccipital decompression on scoliosis curve progression: a preliminary study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003; 28: 2505-9.

- FERNANDEZ A, GUERRERO A, MARTINEZ M, VAZQUEZ M, FERNANDEZ J, OCTAVIO E, LABRADO J, SILVA M, FERNANDEZ DE ARAOZ M, GARCIA-RAMOS R, RIBES M, GOMEZ C, VALDIVIA J, VALBUENA R, RAMON J. Malformations of the craniocervical junction (Chiari type I and syringomyelia: classification, diagnosis and treatment). BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2009, 10(Suppl 1):S1 doi:10.1186/1471-2474-10-S1-S1

- GAMEZ J, SANTAMARINA E, CODINA A. Dysphagia due to Chiari I malformation mimicking ALS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74: 549-50; author reply 50.

- IKUSAKA M, IWATA M, SASAKI S, UCHIYAMA S. Progressive dysphagia due to adult Chiari I malformation mimicking amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 60: 357-8.

- MILHORAT TH, CHOU MW, TRINIDAD EM, KULA RW, MANDDELL M, WOLPERT C, SPEER MC. Chiari I malformation redefined: clinical and radiographic findings for 364 symptomatic patients. Neurosurgery 1999; 44: 1005-17.

- MUTHUSAMY P, MATTE G, KOSMORSKY G, CHEMALI KR. Chiari type I malformation: a mimicker of myasthenia gravis. Neurologist 2011; 17: 86-8.

- MWANG’OMBE N, KIRONGO G. Craniovertebral juncion anomalies seen at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J 2000;77:162-164

- NASH J, CHENG JS, MEYER GA, REMLER BF. Chiari type I malformation: overview of diagnosis and treatment. WMJ 2002; 101: 35-40.

- NATHADWARAWALA K, RICHARDS C, LAWRIE B, THOMAS G, WILES C. Recurrent aspiration due to Arnold-Chiari type I malformation. Br Med J 1992:304:565-566

- OGBOLE G, ADELEYE A, ADEYINKA A, OGUNSEYINDE O. Magnetic resonance imaging: Clinical experience with an open low-field-strength scanner in a resource challenged African state. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice 2012; 3: 137.

- PAULIG M, PROSIEGEL M. Misdiagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a patient with dysphagia due to Chiari I malformation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72: 270.

- PRATTICO F, PERFETTI P, GABRIELI A, LONGO D, CAROSELLI C, RICCI G. Chiari I malformation with syrinx: an unexpected diagnosis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med 2008; 15: 342-3.

- SHEHU B, ISMAIL N, MAHMU M, HASSAN I. Chiari I Malformation: A Missed Diagnosis. Annals of African Medicine 2006; 5: 206-8.

- TOOVEY S, MARCELL B, HEWLETT RH. A case of Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease in South Africa 2006;96:592-3

- UNAL M, BAGDATOGLU C. Arnold-Chiari type I malformation presenting as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in an adult patient. J Laryngol Otol 2007; 121: 296-8.

- WURM G, POGADY P, MARKUT H, FISCHER J. Three cases of hindbrain herniation in adults with comments on some diagnostic difficulties. Br J Neurosurg 1996; 10: 137-42.