|

|

|

CLINICAL CASE/CAS CLINIQUE

WILSON’S DISEASE IN A DRUG ADDICT: A CASE REPORT

MALADIE DE WILSON DÉCOUVERTE DANS UN CONTEXTE DE TOXICOMANIE

E-Mail Contact - NYANGUI MAPAGA JENNIFER :

jenica45@yahoo.fr

Introduction Wilson’s disease is a rare autosomal recessive disorder causing pathological copper accumulation in the liver, brain, and other tissues. Its heterogeneous hepatic, neurological, and psychiatric manifestations often delay diagnosis, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Methods We report the case of a 20-year-old man from Libreville who presented with neuropsychiatric symptoms initially attributed to alcohol, drug, and opioid abuse. Clinical assessment and biochemical investigations supported the diagnosis of Wilson’s disease. Results The patient exhibited behavioural disturbances and mood instability. Chelation therapy with D-penicillamine was initiated, resulting in progressive clinical improvement. No significant adverse effects were observed during follow-up. Conclusion : Although uncommon in sub-Saharan Africa, Wilson’s disease should be considered in young adults with unexplained neuropsychiatric or hepatic symptoms. Diagnostic difficulties and treatment cost remain major challenges. Early identification and timely chelation therapy significantly improve prognosis. Keywords : Wilson’s disease ; diagnosis ; neuropsychiatric symptoms ; D-penicillamine ; Libreville.

Resumé Introduction La maladie de Wilson est une affection autosomique récessive rare entraînant une accumulation pathologique de cuivre dans le foie, le cerveau et d’autres tissus. Sa présentation hétérogène, faite de manifestations hépatiques, neurologiques et psychiatriques, retarde souvent le diagnostic, notamment en Afrique subsaharienne. Méthodes Nous rapportons le cas d’un homme de 20 ans admis à Libreville pour des troubles neuropsychiatriques initialement attribués à une consommation excessive d’alcool, de drogues et d’opioïdes. L’évaluation clinique et les examens biologiques ont permis de confirmer la maladie de Wilson. Résultats Le patient présentait des troubles du comportement et des perturbations de l’humeur. Un traitement chélateur par D-pénicillamine a été instauré, entraînant une amélioration progressive sans effets indésirables majeurs au cours du suivi. Conclusion Bien que rare en Afrique subsaharienne, la maladie de Wilson doit être envisagée chez les jeunes adultes présentant des symptômes neuropsychiatriques ou hépatiques inexpliqués. Les difficultés diagnostiques et le coût du traitement demeurent des obstacles. Un diagnostic précoce améliore nettement le pronostic. Mots-clés Maladie de Wilson ; diagnostic ; symptômes neuropsychiatriques ; D-pénicillamine ; Libreville.

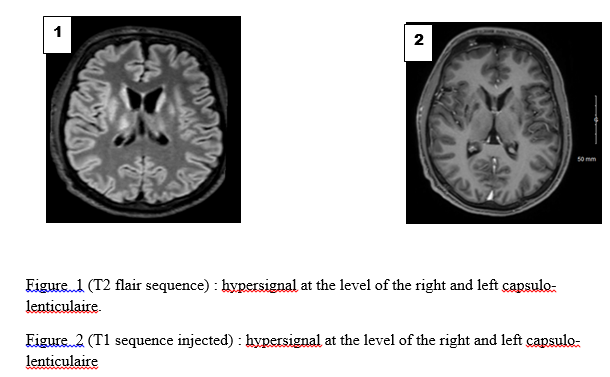

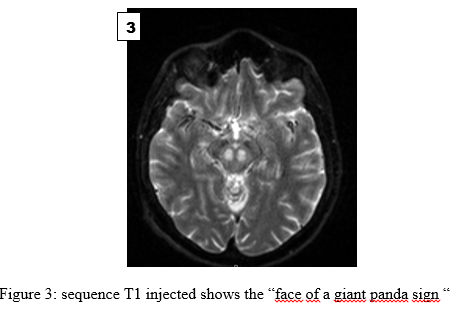

Wilson’s disease (WD) also known as hepatolenticular degeneration is a rare genetic disorder. It was first described in 1912 by Dr Samuel Alexander Kinnier-Wilson [14]. Prevalence varies from 1 in 30,000 to 1 in 50,000, with no sexual or ethnic predominance [10]. It is a monogenic, autosomal recessively inherited condition. The causative gene ATPase 7B located on chromosome 13 and encodes a copper-transporting P-type ATPase [12]. Dysfunction of ATPase 7B leads to reduced biliary excretion of copper, resulting in toxic accumulation of free copper, initially in the liver and secondarily in other organs (central nervous system, haematological, cardiac, renal, endocrine and musculoskeletal systems) [4]. Wilson’s disease presents a variety of clinical phenotypes. Thus, it can be the differential diagnosis of hepatic, neurological or neuropsychiatric pathologies [11]. It can therefore be misdiagnosed or missed from the start, due to the broad spectrum of symptoms. We present the case of a 20-year-old young man in neurology at the Libreville University Hospital, who was diagnosed with WD in the context of drug addiction. Case Report The case involved a 20-year-old man who had been using cannabis, alcohol and morphine for 1 month. He reported a tendency towards aggressiveness and had left the family home 1 month earlier. Found by the side of the road, he was taken to emergency by road users. The ideomotor slowing and tremor suggested toxic encephalopathy as the most likely hypothesis. Cerebral CT (Computed Tomography) showed hypodensity in the midbrain. The patient was transferred to neurology, where examination revealed anarthria, a kineto-rigid parkinsonian syndrome and a dystonic posture. Cerebral MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) showed bilateral, symmetrical lesions, centropontically located, in the cerebral peduncles and in the lenticular nuclei, hypersignal T2, hyposignal T1, without contrast (figures 1, 2). But also, the symmetrical hyperintensities in both halves of midbrain and periaqueductal gray matter with hypointense red nuclei and subtantia nigra (figure 3). Biological tests showed no ionic disturbances or cytolysis syndrome. Gamma GT and alkaline phosphatase levels were 4 times higher than normal. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a heterogeneous dysmorphic liver of normal size with micro-bosselated contours. In the hypothesis of Wilson’s disease, the Kayser Fleischer ring was sought and observed with a slit lamp. Ceruloplasmin and cupremia were down respectively to 0.03 g/l and 4.92 µmol/l. An increase in the exchangeable copper ratio (ECR) to 49.8% was noted. Cerebrospinal fluid copper was increased to 86.8 µg/l and ATP 7B mutation was found. Anti-neuronal antibodies and urinary toxins were negative. Symptomatic treatment with a combination of levodopa and carbidopa 100/10 mg was started at a progressive dose, with dose increases every 5 days. The patient was evacuated to Morocco. He is currently on D-penicillamine with progressive dose adjustment and 24-hour cupruria monitoring. The clinical and biological course was favourable after 1 week. Family screening was refused. WD is present at birth, symptoms most often appear between the ages of 6 and 20, but the onset may be later in life [1]. Our patient also presented manifestations during the second decade of life. The clinical feature is polymorphous. However, its main manifestations are hepatic (40–60%), neurological (40–50%) and psychiatric (10–25%). Most patients present with hepatic manifestations in the second decade of life, while some are diagnosed in the third and fourth decades on the basis of neurological or psychiatric signs [8,7]. The neurological symptoms of WD are varied, but most refer to the dysfunction of the extrapyramidal system as in our patient’s case [4]. The neuropsychiatric symptoms of WD vary widely among individual patients. These symptoms can be confused with other disorders ranging from depression to schizophrenia, and are often misdiagnosed as substance abuse. Indeed, in our case drug consumption masked the diagnosis of WD. The presence of the Kayser Fleischer ring helped to orient the diagnosis towards Wilson’s disease, the most important diagnostic sign observed in over 90% of patients. Brain MRI is characteristic, showing the ‘classic giant panda face sign’. First described in 1991 by Hitoshi, this imaging finding is highly specific but rare in WD [15,6]. It is characterised by T2 hypersignals surrounding the red nuclei and substantia nigra [1]. Other signs include symmetrical hypersignals of the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem on T2 or FLAIR sequences, as observed in our patient. Diffuse cerebral atrophy is frequently found in white matter patients. Hypersignals of the substance can lead to misdiagnosis. Indeed, they may suggest metabolic disorders such as hepatic or uraemic encephalopathy, methanol intoxication or extra pontine myelinolysis. Mitochondrial diseases are also cited (Leigh’s disease), as are infectious causes and many others [13]. No laboratory test is currently considered to be perfect and specific for WD. It is notable that clinical symptoms may be absent in the majority of patients. The Leipzig score, a diagnostic score based on all available tests proposed by the working group of the 8th International Meeting on WD, has been demonstrated to offer satisfactory diagnostic accuracy [5]. Although WD occurs in people of all ethnic backgrounds, certain populations, such as those of European, Mediterranean, or Asian origin may be more frequently affected due to genetic predisposition. A limited number of cases have been documented in the sub-Saharan region in recent decades [2]. It is likely that the prevalence of the disease in our region is underestimated due to the lack of accessible diagnostic methods. Indeed, the biological workup of our patient was sent abroad for analysis, as the requisite diagnostic tests are not available in the region. Unless measures are taken to eliminate excess copper, WD is fatal. This can be achieved either by copper chelation or by blocking intestinal copper absorption with zinc. It is recommended that family members of the index case be systematically screened in order to identify and treat early symptomatic and asymptomatic cases. In the case presented here, the family chose not to know their status, due to socio-cultural considerations in the African context, and so the test was not carried out. The aim of this case study is to clarify whether there is an association between Wilson’s disease and the use of cannabis, alcohol and morphine. To determine whether the neuropsychiatric manifestations are exacerbated by the use of these substances. As mentioned by Raianny et al., in a patient with WD and a marijuana user. They suggested that marijuana may have increased copper deposition in the central nervous system (CNS) and led to the onset of neuropsychiatric manifestations [9]. Cannabis, alcohol, or morphine may be responsible for psychiatric manifestations [12]. They are also metabolised by the liver. They probably increased the deposition of copper in the CNS. Conclusion Wilson’s disease is a rare, polymorphic disorder. It can mimic several toxic, metabolic, degenerative, inflammatory, and infectious diseases. However, brain MRI significantly increases the probability of diagnosis, with the pathognomonic ‘giant panda’ sign. Early treatment improves prognosis. It may be an underestimated affection due to diagnostic difficulties and costly therapy. Statement of EthicsStudy approval statement: ethics approval was not required Consent to publish the statement: Verbal informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of case details and accompanying images.Conflict of Interest StatementThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.  References

|

© 2002-2018 African Journal of Neurological Sciences.

All rights reserved. Terms of use.

Tous droits réservés. Termes d'Utilisation.

ISSN: 1992-2647