CASE REPORT / CAS CLINIQUE

CEREBRAL HYDATIDOSIS. CASE PRESENTATION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

- Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Kenyatta National Hospital, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

E-Mail Contact - MWANG’OMBE N. J. M. :

SUMMARY

Cerebral hydatidosis is a rare form of hydatid disease of the Central Nervous System accounting for 2 to 3 percent of all cases of hydatid disease. Hydatid disease is a major health problem in certain nomadic communities in Kenya. Treatment is surgical excision of the cyst. A four year old African boy presented with fits, progressive enlargement of the head and right hemiparesis at the Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. A computerised tomography (CT) scan of the head showed a large cystic mass in the left parietal area with no associated brain oedema or contrast enhancement. A left parietal craniotomy and total excision of the cystic mass was done. Histology showed laminated wall of cyst of echinococcus granulosus with numerous scolices. Post-operative recovery was good and follow-up has not revealed any evidence of recurrence.

Keywords : Cerebral Hydatidosis, Kenya

RESUME

L’hydatidose cerebrale est observee chez environ 2 a 3% des patients qui presentent une hydatidose. L’hydatidose est un des problemes de sante publique majeur observe au sein de communautes nomades vivant au Kenya. Le traitement est 1’ablation chirurgicale du kyste. Un cas survenu chez un garcon agé de 4 ans ayant des crises d’epilepsies, une macrocephalie et une hemiparesie droile a ete observe a l’Hopital National de Kenyatta a Nairobi. L’examen tomodensitometrique cranien a montre I’existence d’un grand kyste situe dans la region parielale gauche sans oedeme cerebral et sans rehaussement apres injection de produil contraste. Une craniotomie parie’tale gauche a permis 1’excision totale du kyste, avec a l’examen histologique une confirmation de la nature du kyste qui contenait de nombreux scolex. Une regression des signes cliniques est apparue apres 1’intervention sans recidive de l’affection.

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral hydatidosis is caused by the larval stage of hydatid of the dog tapeworm taenia echinococcus. Hepatic and pulmonary forms of the disease are the most common and account for almost 85% of the cases.

Involvement of the Central Nervous System (CNS) is seen in 2 to 3 percent of the patients. Hydatid disease is caused either by ingestion of the hexacanth embryo (scolex) or ingestion of eggs that may be present on infected food stuffs. Infection in children may occur accidentally through contamination with faeces of dogs harbouring the adult worm, Echinococcus granulosus. In adults the disease is most commonly contracted by ingestion of eggs on contaminated food stuffs. The usual hosts of the adult worms are dogs, wolves and foxes. Cattle sheep and hogs serve as intermediate hosts. Man also may serve as intermediate host. If the scolex is ingested by the definitive host it will attach itself to the intestinal mucosa and the adult worm will form. If the scolex is ingested by the intermediate host a larval stage called the hydatid will form. Celebral echinococcosis is considered a childhood disease and 50-75% of the cases involving the CNS occur in the paediatric age group.(1).

In this paper a case ot cerebral hydatidosis in a child treated at the Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, is presented and discussed.

CASE REPORT

A four year old African male was admitted to the Neurosurgical Unit at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya, with a one year history of persistent headache and grandmal seizures. He had previously been admitted and treated in various hospitals elsewhere on several occassions for what was then thought to be attacks of malaria. He was referred to Kenyatta National Hospital from the Kakuma refugee camp where he was

residing as a refugee from Sudan. Three months prior to admission he had developed progressive enlargement of his head accompanied by right-sided weakness.

His previous medical history was insignificant. Family history was also unremarkable. He was a second born in a family of two and his father was a soldier with the Sudanese People Liberation Army (SPLA). He had been in the refugee camp with his mother for the past two years.

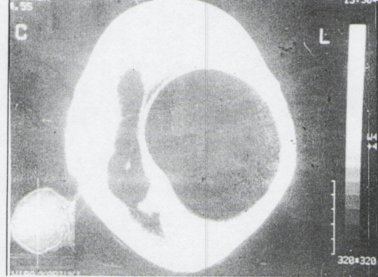

On examination, he was found to be sick looking although fully conscious and co-operative. He had marked right side wcakeness with power in the upper and lower limbs reduced to grade 3/5. The deep tendon reflexes were brisk. His head circumference was 56cm. A computerised tomography (CT) scan of the head showed a large cystic mass in the left parietal area, with mass effect. There was no rim enhancement on injection of contrast materia (Fig 1)

There was no associated oedema.

Blood results were as follows:

Urea3.1 mmol/L,Na+ 138 mmol/L. K+3.6 mmol/L, Hb 12.9g/dL,WBC 7.3xl0/L Platelet 413 x 10/L. LSR 26mm/hr.

Liver function tests were as follows:

Total protein 77g/L. Albumin 37g/L, SGT239U/L. AST 36 U/L

Total bilirubin 3.4 mmol/L and direct bilirubin 1.6 mmol/L.

Chest x-ray was normal.

Abdominal ultrasound showed features suggestive of hepatic hydatidosis. Patient was pre-operatively put on albendazole, prepared for surgery and underwent craniotomy under a general anaesthetic. The mass was excised in toto. Histology showed laminated wall of cyst, typical of echinoccocus granulosus with numerous scolices. His post operative recovery was uneventful with good recovery of power on the right side and improvement of his symptoms.

DISCUSSION

The existence of the hepatic form of hydatid disease was recognised by Hippocrates and Galen in their early writing (2). The first reports of cerebral hydatid disease and vertebral echinococcosis were by Guesnard and Chaussier respectively in 1807 (3). Hepatic and pulmonary forms of the disease arc the most common and account for almost 85 per cent of the cases (4). Cerebral hydatidosis accounts for 2 to 3 per cent of patients. Central nervous system forms of the disease may be cerebral (80 %), cranial (5%) and vertebral (15 %).

Hydatid disease is caused either by ingestion of the hexacanth embryo (scolex) or ingestion of eggs that may be present on infected food stuffs.

The ‘usual hostsfor the adult worms are dogs, wolves and foxes. Cattle, sheep and dogs serve as intermediate hosts. In the definite hosts, the scolex attaches to the intestinal mucosa. becomes the adult worm and releases eggs into the faeces of canines. After ingestion of the egg by man, the capsule is digested and hexacanth oncospherc is released in the jejunum where it penetrates the intestinal mucosa and passes into the portal circulation. Most become entrapped in the small intrahepatic venules while others pass to the lungs, central nervous system, bone and other site (1). The embryo, oncospheres, may be destroyed by normal hosts defense mechanisms or may increase rapidly in size and form unilocular cysts. The cyst wall differentiates into an internal granular layer (endocyst) and an outer cuticular laminated layer surrounded by an outer host adventitial fibrous capsule. The cavity of the cyst contains hydatid fluid, daughter cysts, brood capsules and scolices. Brood capsules arise from the germinal layer of the endocyst. Brood capsules and scolices within the hydatid cyst fluid form the hydatid sand (5).

Important epiclemiological factors in spreading the disease indirect contact with dogs that shed ova in their faeces and consumption of contaminated food and water.

Cerebral cchinococcosis is more common in children, 50-75% of cases, with an equal male to female ratio. There is an unexplained predilection for white matter.

Clinical manifestations are primarily related to increased intra cranial pressure and include headache and vomiting. In children the progression of symptoms may be gradual with later development of focal deficits.

Papilloedema is usually present. Seizures are also common.

A detailed clinical examination is important in making a diagnosis. Several immunological tests are also available which aid in making a diagnosis (Weinberg’s compliment fixation test and Casoni’s intra dermal skin test). Computerised tomography scanning reveals an intra parenchymal lesion with a clearly defined margin which does not enhance on injection of contrast material. There may be mass effect and associated hydrocephalus but cerebral oedema is absent (6,7). Magnetic resonance imaging will also demonstrate the presence of the cyst.

Definitive diagnosis is dependent upon indentification of the parasite or its body parts in the lesion.

Plain skull radiographs may show evidence of increased intracranial pressure. In children, diastasis of the sutures, erosion of the sella and thinning of the bone overlying the lesion may be observed. Calcification of the cyst wall may occur but is not common.

Angiography is the procedure of choice where computerised tomography scanning is not available. Typical features are an avascular mass with stretching of normal vessels (8).

Follow-up post operative CT scans show that re-expansion of the brain is gradual and extra-axial collection of fluid may remain for a long time. The previous cyst site may also completely disappear (7). Study of electrical activity over the brain may demonstrate a silent focus surrounded by a zone of’delta activity (9).

Successful operative treatment depends upon complete removal of the unruptured cyst. Attempts should therefore be made to remove the cyst in loto. If rupture of the cyst occurs, irrigation with hypertonic salin should be done (7) to destroy the organisms by osmotic dessication. Prognosis usually depends on location and size of the lesion, presence of single or multiple lesions and the presence of contamination. Fortunately cerebral lesion are usually single and accessible.

Figure 1

REFERENCES

- AYRES, C., DAVEY, L.M. and German. W.J. Cerebral hydatidosis. Clinical case report with a review of pathogencsis. J. Neurosurg., 20:371-377,1963.

- DEW, U.K., Hydatid Disease. Its pathology Diagnosis and Treatment. Sydney, The Australasian Medical Publishing Co, Ltd. 1928.

- CHAUSSIER. Un cas de paralysic dcs membres inferieurs. J. MED. Chir. Pharmacol., 14:231-237, 1807.

- BALDING, D.L., Textbook of Parasitology 3rd cd.New York. Appleton-Century – Crafts, 1965 pp 626-640.

- DHARKER, S.R., VAISHYA. N.D., SIIARMA, M.L. and CHAURASIA, B.D.. Cerebral hydatid cysts in Central India.Surg. Neurol, 8:3 1-34. 1977.

- ABBASS10UR, K., SA1-IMAT. II. AMI-:LI. N.O. and TAFAZOB, M. Computerised tomography in hydatid cysts of the brain. .1. Neurosm’i;. 49:408-411.1978.

- OZGEK T., ERBENGI. A.. BEKTONI. V..SAGLAM. S..OZDEMER, G., AND PUNOR, T.The use of computerise tomography in the diagnosis of cerebral hvdatid cvsts. .1. Neurosurg, 50:339-342,1979.

- ARANA-lNlGUEZ. P.R.. and SAN JULIAN, J.Hydatid Cysts ot’the brain. J. Neurosurg., 12:323-335,1955.

- FUSTER, B., The EEC, in hydatid cysts of the brain. In Van Bogaert, L.. Pereyra Kafer, .1. and Poch, (i.F. eds.Tropical Neurology. Buenos Aires, 1963.pp 128-139.