|

|

|

CLINICAL STUDIES / ETUDES CLINIQUES

CLINICO-LABORATORY FINDINGS OF PATIENTS WITH MYASTHENIA GRAVIS IN KENYA: A 10 YEAR RETROSPECTIVE STUDY

RÉSULTATS CLINIQUES ET PARACLINIQUES DE PATIENTS ATTEINTS DE MYASTHENIE AU KENYA : UNE ÉTUDE RÉTROSPECTIVE DE 10 ANS

E-Mail Contact - BUNDI KARAU Paul :

pbkarau@gmail.com

ABSTRACT Background Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an important condition of the neuromuscular junction. In our local population, there is paucity of data on the epidemiological and clinico-laboratory characteristics of the disease. The aim of this study was to evaluate the demographic, clinical and laboratory features of patients with myasthenia gravis presenting at the Kenyatta National Hospital. Methods This was a descriptive cross-sectional study using patient records for the years 2008-2017. Data on the socio-demographic, clinico-laboratory characteristics, subtype of MG at presentation and outcome was abstracted from files, entered into SPSS 21.0 and analyzed. Descriptive statistics were used for sociodemographic characteristics and other descriptive variables. Results A total of 48 patients were treated for MG over the 10-year period. The mean age was 28.2 years. There was a female preponderance of 58.3%. The mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis (diagnostic delay) was 11.2 months (range 2-48 weeks), and the commonest initial sign noticed by the patient was ocular (60.4%), followed by weakness of extremities (22.9%). Majority had Osserman-Genkin stage IIa (35.4%) and III (35.4%). The commonest cause of death was MG-related respiratory failure and aspiration pneumonia. Conclusion This is the first study to document epidemiology and clinical features of myasthenia gravis in Kenya. MG occurs in Kenya, is more common in females, and occurs mostly in the third decade of life (20-30). We hope that this study will help raise the awareness of this rare disorder, and increase research into the diagnosis and effective treatment of myasthenia gravis. Keywords: Myasthenia gravis, epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, outcomes. RÉSUMÉ Contexte La myasthénie (Myasthenia Gravis, MG) est une affection importante de la jonction neuromusculaire. Dans notre population locale, il y a peu de données sur les caractéristiques épidémiologiques, cliniques et paracliniques de la maladie. L’objectif de cette étude était d’évaluer les caractéristiques démographiques, cliniques et de laboratoire des patients atteints de myasthénie grave se présentant à l’hôpital national Kenyatta. Méthodes Il s’agit d’une étude transversale descriptive utilisant les dossiers des patients pour les années 2008-2017. Les données sur les caractéristiques sociodémographiques, cliniques, paracliniques, le sous-type de MG au moment de la présentation et les résultats ont été extraites des dossiers, saisies dans SPSS 21.0 et ont fait l’ojet d’une analyse statistique descriptive. Résultats Au total, 48 patients ont été traités pour une MG au cours de la période de 10 ans. L’âge moyen était de 28,2 ans. Il y avait une prépondérance féminine de 58,3 %. La durée moyenne des symptômes avant le diagnostic (délai de diagnostic) était de 11,2 mois (de 2 à 48 semaines), et le signe initial le plus fréquent était oculaire (60,4 %), suivi de la faiblesse des extrémités (22,9 %). La majorité des patients était au stade IIa (35,4 %) et III (35,4 %) de la classification d’Osserman-Genkin. La cause de décès la plus fréquente était l’insuffisance respiratoire liée à la MG et la pneumopathie d’aspiration. Conclusion Cette étude est la première à documenter l’épidémiologie et les caractéristiques cliniques de la myasthénie au Kenya. La MG est présente au Kenya ; elle est plus fréquente chez les femmes et se manifeste principalement au cours de la troisième décennie de la vie (20-30 ans). Nous espérons que cette étude contribuera à sensibiliser le public à cette maladie rare et à développer la recherche sur le diagnostic et le traitement efficace de la myasthénie grave. Mots-clés : Myasthénie grave, épidémiologique, clinique, laboratoire, résultats. INTODUCTION Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a rare disease of the neuromuscular junction characterized by exertional weakness of skeletal muscles. It is caused by autoantibodies directed at the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) on the postsynaptic neuromuscular junction. It was initially thought to be a disease of young women, but population studies have shown involvement of older women and men. Prevalence of MG in the developed world ranges from 1 in 50, 000 to 1 in 10, 000, and current estimates from North America suggest the prevalence of MG to be about 19 – 21 per 100 000 population (12). There has been a substantial increase in diagnosis in older age groups, with those over the age of 50 years constituting up to 60% of newly diagnosed seropositive MG (SPMG) cases (9). The incidence of MG has been found to be similar across racial groups, although one study found a trend towards a higher incidence in young African-Americans from Virginia (11). In the African population, delay in seeking care means that patients present with late disease (4). There are few studies on the epidemiologic, clinico-pathologic and outcomes of patients with MG in Africa. In the East African region, a study done in Tanzania over a 10 year period (1988-1998) among 47 patients found an annual incidence of 3 per 1 million population (8). This corroborates an earlier study done in Libya, which reported an incidence of 4.4 per 1 million populations, much lower than that reported in developed countries (13). No epidemiological data is available on MG in Kenya. A personal communication by Harries reported one case of MG in Kenya in 1956 (4), and a further 9 cases (5 Africans, 2 Asians and 2 Europeans between 1956 and 1969 (5). The reported racial and evolving characteristics of the disease implies that local studies are necessary to characterize the disease. MATERIALS AND METHODS This was a descriptive cross-sectional, retrospective study for the period 2008-2017. The study was conducted at the records department of Kenyatta National Hospital. Records of all patients with ICD-10 diagnosis of MG were retrieved for the period. The Health Records Department of Kenyatta National Hospital keeps an archive of all patient records, as well as an electronic database of patients’ conditions every year. Any patient with a file diagnosis of MG was eligible for enrolment into this study. This included patients with a clinical diagnosis of MG (confirmed by a neurologist in a ward round as documented in the file), and those with positive AChr or positive findings on nerve conduction studies. We determined from the file the status of the patient at the end of the study period. The patients were classified as alive, alive and on follow up, lost to follow-up or dead. The following study variables were obtained

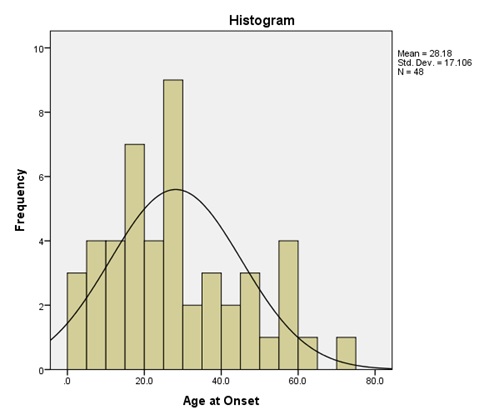

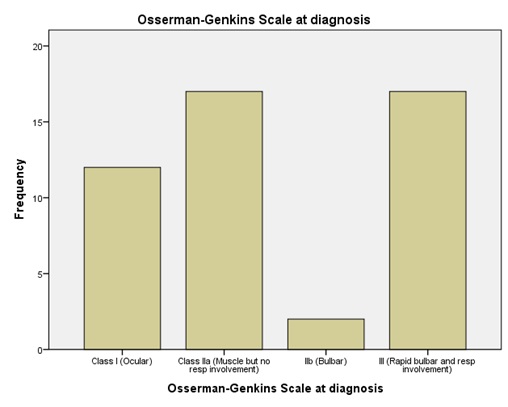

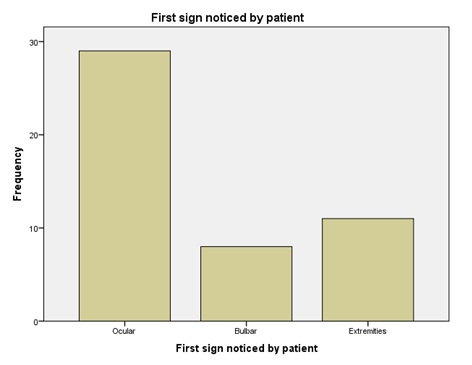

We sought and received ethical approval from Kenyatta National Hospital-University of Nairobi Ethics and Review Committee. Patient confidentiality was observed and no direct patient identifiers were used in the data abstraction. Data was coded and entered into SPPS version 21.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics such as means, proportions were used, while data was displayed in charts and graphs. RESULTS A total of 48 patients satisfied the diagnostic criteria over the study period. The mean age was 28.2 years (8 months-70 years). There was female preponderance (58.3%) and males 41.7%, with a male-female ratio 1:1.4. Most patients originated from Central Kenya (56.3%), Eastern (25.0%), Nyanza (8.3%). Figure 1 shows the age distribution of study subjects. Mean duration of symptoms (diagnostic delay) was 11.2 months with a range of 2 weeks and a maximum of 48 weeks. Most patients noted ocular signs such as diplopia, visual fatigue and drooping of eyelids as the first symptom of myasthenia gravis. Figure 2 illustrates the first sign noted by the patient prior to presentation in the hospital. At diagnosis, most patients had muscle involvement with respiratory involvement (35.4%), while a small number had pure bulbar involvement. Figure 3 illustrates the Osserman-Genkins scale of the patients at diagnosis. Diagnosis was made by typical history and examination in 100% of cases, with acetylcholine receptor antibodies assayed in 39.6% of cases. There was no case of anti-MUSK antibodies assayed. Repetitive nerve stimulation was also not performed on any patient. Patient outcomes were as follows: 68.8% of patients improved before discharge, 16.7% died, while 6.3% went into remission. The commonest cause of death was myasthenia-related respiratory failure and aspiration pneumonia (14.6%). On follow up, it was found that 52.1% of patients were alive 2 years after diagnosis, while 14.6% were alive more than 2 years after diagnosis. 25% of the patients died during follow up, while 8.3% were lost to follow up. DISCUSSION To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive descriptive study of MG in Kenya, and sheds light on some epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the disease. MG is reported to be a rare disease in Africa, but this may be attributable to lack of awareness by patients and health care providers. Epidemiological characteristics mirror those in Tanzanian (8) and Libyan study (13) with the 20s decade being most affected, but differ from European studies where older patients are mostly involved (11) . The Male: Female ratio of 1:1.4 is almost similar to 1:1.3 reported in Tanzania (8). A mean duration of symptoms of 11.2 months represents a significant delay in diagnosis. This is much lower (2 months) in Korea (10), and up to 36 months in Tanzania (8). This diagnostic delay could be attributed to delay in healthcare seeking, difficulties in coming up with the diagnosis, inadequate trained personnel (neurologists) and inefficient referral system. Ocular signs (Ptosis) are the most frequent initial manifestation (60%), and this is in keeping with African (1), and Asian studies (6,14). Patients presenting with ptosis and diplopia therefore require further examination and work-up for possible myasthenia gravis. At presentation, majority of patients have grade II and III disease, with generalized disease. An Italian study found over 90% of patients had Osserman grade II disease at diagnosis (7). These finding sheds light on the likely prognostication of patients seen with myasthenia gravis, and calls for a high index of suspicion when handling myasthenia gravis suspected cases. We found low utility of Acetylcholine receptor antibody assay in our study. Only 39.6% of patients were subjected to this test. This may be explained by financial constraints and relative inaccessibility of the test in our setting. No assay for muscle specific tyrosine kinase antibodies despite their key role in pathogenesis of disease. Indeed, both tests are not available in Kenya, and two laboratories able to do this test in South Africa (1). This underscores the need for high index of suspicion, thorough history and examination. There was a high prevalence of deaths at first admission; attributable to late presentation or delay in seeking health care. Only 14.6% of the patients were alive more than 2 years after diagnosis. This portends a worse prognosis than most infectious diseases, cancer and heart failure, but more studies need to be done to elucidate more on this aspect. High mortality (25%) within 2 years of diagnosis points to suboptimal follow-up and failure to put disease into remission. CONCLUSION This is the first study to document epidemiology and clinical features of MG in Kenya. We hope that this study will help raise the awareness of this rare disorder, and increase research into the diagnosis and effective treatment of MG. MG occurs in Kenya, is more common in females, and occurs mostly in the third decade of life (20-30 years). Low capacity to confirm antibodies to ACHR and Musk- calls for traditional approach of high index of suspicion, history and examination. There is need for close follow-up to avert the high mortality associated with the disease.

Figure 2: Showing the first clinical manifestation noticed by the patient before presentation to hospital

REFERENCES

|

© 2002-2018 African Journal of Neurological Sciences.

All rights reserved. Terms of use.

Tous droits réservés. Termes d'Utilisation.

ISSN: 1992-2647