|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

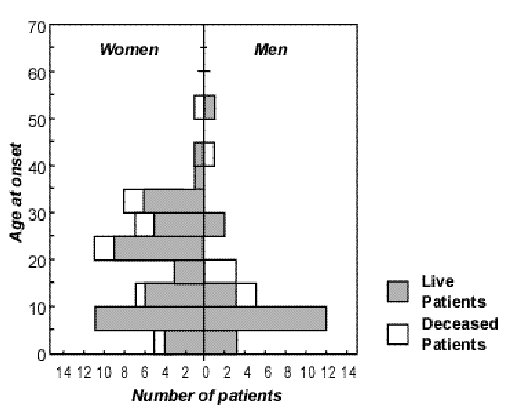

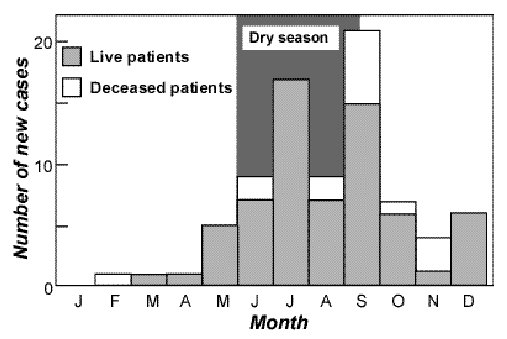

The African Journal of Neurological Sciences ( AJNS) is still being published despite several and recurrent difficulties encountered, thanks to R. RUBERTI’s determination and willingness to give of his time. By so doing, he has carried on the task and we highly commend him for the excellent work he has accomplished !! The editorial committee’s ambition is to publish a first rate medical scientific journal. The work published will meet a scientific requirements at the highest level taking into account the hard realities in the field. Indeed, it is our responsibility to be in charge of, with limited medical and economic means, the ’neurological » health of 4 billion persons – the South -representing 2/3 of the world population. Given the ever widening economic gulf between the North and the South, it is not sufficient to protest strongly and shout loud and clear about the necessary and legitimate need for human solidarity to ensure that all human beings benefit from medical care with dignity and on an equal basis. It is clear that this appeal has been in vain. Man’s selfishness …. This then is the reality. Lack of technical and financial means hinders the development of our respective fields of study in Africa. Nevertheless, there is great hope of making up for this delay, if we take into account the willingness to act and the ambition of the agents in the field- – without forgetting those, outside Africa, who are not willing to be fatalistic or resigned. Let us remember that the first heart transplant was carried out in an African country. We have to fight. We have to be creative and innovative if we intend to provide quality care to our families and our friends. To practice our profession in Africa and for Africa requires faith, willingness, self-sacrifice and determination. These qualities need to be revamped over and over again and maintained at all times. Thus, apart from its scientific aspect, the AJNS plans to maintain and reactivate the motivation of all our colleagues who, faced with many social, family, economic and political obstacles and problems are driven to despair. The AJNS should provide a link bringing all of us together and all the societies striving to fight against neurological diseases. The editorial board should be in a position to count on our contribution. The ANJS belongs to us. Let us play an active role in its running. Let us keep our journal alive so that our modest contribution may bring a little happiness to our people who so much need it. EDITORIAL (fr)Grâce à la grande disponibilité et la ténacité de R.RUBERTI, l’African Journal of Neurological Sciences (AJNS) a continué à paraître malgré les nombreuses et récurrentes difficultés qu’il a rencontrées. R. RUBERTI a transmis le flambeau et nous le félicitons chaleureusement pour l’excellent travail qu’il a accompli !! L’ambition du comité éditorial est de publier une revue scientifique médicale de tout premier plan. Une référence. Les travaux publiés répondront à une exigence scientifique de haut niveau en tenant compte des difficiles réalités vécues sur le terrain. En effet, il nous incombe de prendre en charge, avec des moyens économiques et médicaux limités, la santé “neurologique” de 4 milliards de personnes – pays du Sud- représentant les 2/3 de la population mondiale. Le fossé économique entre le Nord et le Sud ne cesse de se creuser et ce n’est pas faute de clamer haut et fort la nécessaire et légitime solidarité humaine pour faire en sorte que tous les êtres humains puissent bénéficier de soins médicaux en toute égalité et dignité. Force est de constater que cet appel reste vain. L’égoïsme des hommes…. La réalité est donc là. Le manque de moyens financiers et techniques entrave le développement de nos disciplines respectives en Afrique. Cependant l’espoir est grand de rattraper le retard si l’on se réfère à la volonté d’agir et l’ambition des acteurs sur le terrain – sans oublier ceux, en dehors de l’Afrique, qui ne veulent pas faire preuve de fatalisme et de résignation. N’oublions pas que la première greffe cardiaque a eu lieu dans un pays africain. Il faut se battre. Il faut faire preuve de créativité et d’innovation si l’on veut apporter des soins de qualité à nos familles et à nos amis. Pratiquer notre art en Afrique et pour l’Afrique exige foi, volonté, abnégation et détermination. Ces qualités demandent à être sans cesse renouvelées et maintenues. Ainsi outre son volet scientifique l’AJNS se propose d’entretenir et de réactiver la motivation de tous les confrères qui, confrontés à de multiples embûches et problèmes “socio-familio-économico-politiques”, sont poussés au désespoir. L’AJNS doit être un lien nous unissant tous par le biais de la PAANS et de toutes les sociétés savantes uvrant pour lutter contre les affections neurologiques. Le comité éditorial sait pouvoir compter sur votre contribution. L’AJNS nous appartient. Prenons une part active à son fonctionnement. Faisons vivre notre revue afin que notre modeste contribution puisse permettre d’apporter un peu de bonheur à notre monde qui en a tant besoin. LA SCLEROSE EN PLAQUES EN AFRIQUE NOIRERESUME Description Objectif Méthodologie Résultats Conclusions Mots clés : Afrique, épidémiologie, sclérose en plaques ABSTRACT Description Objective Methodology Results Conclusion Keywords: Africa, epidemiology, multiple sclerosis La sclérose en plaques (SEP) se caractérise classiquement par une prévalence selon un gradient Nord-Sud. Les taux de prévalence de la SEP croissent rapidement en direction du pôle puis décroissent à sa proximité. Ils décroissent également rapidement en direction de l’équateur (39). La revue de la littérature confirme l’apparente rareté de la sclérose en plaques en Afrique noire (1,37,38). L’absence d’enquêtes de populations et de données épidémiologiques pertinentes font classer cette région du monde dans une zone où la maladie reste probable mais exceptionnelle. Les infrastructures neurologiques et la SEP Le nombre de neurologues et les moyens de diagnostic sont essentiellement concentrés dans la partie nord et sud du continent (36). Entre ces deux ensembles, dans la partie équatoriale et intertropicale, on compte 1 neurologue pour 1 à 5 millions d’habitants. COLLOMB et al (17) déjà dans les années 1960 attiraient l’attention sur les difficultés de diagnostic de la SEP en Afrique : la validité du diagnostic, l’observation du malade limité à une courte période, la difficulté à suivre les malades à leur sortie de l’hôpital, l’équipement médical insuffisant. La rareté de la SEP en Afrique noire ne peut être expliquée seulement par l’absence, la rareté et la modestie des infrastructures neurologiques. Épidémiologie de la SEP en Afrique Au sud du continent En Afrique de l’Ouest. En Afrique de l’Est, En Afrique centrale, Au nord du continent, La SEP chez les Noirs aux USA Le taux de prévalence de la SEPest plus élevé chez les blancs que chez les noirs indépendamment de la latitude mais reste plus élevé dans les deux communautés dans la partie nord que la partie sud (5). Par exemple le taux de prévalence à Boston (latitude 42°) est même plus élevé chez les noirs que chez les blancs à Halifax (latitude 44°). Cette même constatation a été faite par KURTZKE et al (40), BEBEE et al (8) dans l’armée américaine. D’après M.ALTER et M. HARSCHE (4), le seul facteur racial ne peut expliquer ce phénomène. La différence dans le risque chez les noirs africains et les noirs américains devrait être génétique ou environnemental. Pour P. H. PHILLIPS et al (46) les formes de “neuromyélites optiques” seraient les manifestations les plus fréquentes de la SEP chez les Américains d’origine africaine dans sa série. L’atteinte ophtalmologique serait plus sévère. La même constatation a été faite en Afrique australe (26). Pour d’autres auteurs (44), l’âge de début de la SEP, et le profil évolutif peuvent être déterminés par des facteurs génétiques et environnementaux. La SEP dans les populations noires ayant immigrés vers les zones de fortes prévalence (Londres) Les Africains (Afrique de l’Ouest et de l’Est) dans le Grand Londres présentent les mêmes risques que ceux de leurs pays d’origine (24). Par contre leurs enfants nés en grande Bretagne présentent les mêmes risques que ceux de leur pays d’adoption (28-30) . Ces recherches ont confirmé le facteur de risque age dépendant et plaident fortement en faveur d’un facteur de risque environnemental. Les facteurs génétiques La susceptibilité génétique a été mise en évidence chez les sujets de race différente atteints de SEPpar l’étude du système HLA et des immunoglobulines (16,31,41). Elle est sous la dépendance de plusieurs gènes dépendants ou non du complexe majeurs d’histocompatibilité (CMH). En Europe du Nord, on constate une forte liaison avec HLA classe I (A3 et B7) mais surtout classe II (DR2 et DQW1). Les Lymphocytes T (récepteurs a et b) semblent jouer un rôle sans exclure d’autres loci (20 ). Les facteurs environnementaux Depuis les années 1970, les différents travaux épidémiologiques ont montré le rôle indiscutable des facteurs environnementaux (exogène et ou endogène) et d’un risque âge dépendant dans la survenue de la SEP. Le rôle d’un agent infectieux, viral est régulièrement évoqué (3,5). Le rôle des rayons UV-B dans la distribution géographique de la SEPa été soulevé (15). Les UV-B décroissent au fur et a mesure que l’on s’éloigne de l’équateur tandis que la prévalence de la SEP augmente. Les UV-B aurait une activité immunodépressive particulièrement sur l’activité des cellules T c’est à dire sur l’activité autoimmune (43). Pour C.E. Hayes et al (35) la vitamine D 3 a été capable de prévenir dans le modèle expérimental de la SEP chez la souris, la survenue de l’encéphalomyélite allergique expérimentale. Le degré d’exposition aux UV conditionne la production de la vitamine D3 et constitue un immunorégulateur avec une inhibition des maladies autoimmunes. Le degré d’exposition aux UV expliquerait la différence de prévalence de la SEP chez des populations habitant les mêmes latitudes mais avec un ensoleillement différent. Pour d’autres auteurs (27,52) les rayons UV modulent la sécrétion de la mélanine à partir de la puberté et expliquerait l’existence du facteur de risque âge dépendant et la distribution raciale et géographique de la SEP. Le régime alimentaire, en particulier, le rôle de certains acides gras a été évoqué par certains auteurs. Peu d’études ont été menées en Afrique sur la SEP, les formes familiales n’ont pas été rapportées (20% en Europe) alors que les maladies génétiques (consanguinité) sont habituelles dans le continent noir. En Afrique du Nord, les formes cliniques sont identiques à celles rapportées ailleurs. Conclusion La SEP reste relativement rare chez le noir africain. L’intérêt pour la SEP manifesté par de nombreux auteurs en Afrique depuis les années 1960, n’a débouché que sur une douzaine d’observations colligées en 1990 au Sud de l’Afrique et quelques observations indiscutables rapportées au Sénégal (1961; 1970), et au Kenya (1994.) La prévalence de la SEP dans les populations noires (américaines et immigrés en Europe) dépendrait du degré de mélange avec les populations blanches (47,48). Les nombreux cas de SEP qui ont été rapportés ces dernières années en Afrique du Sud chez des “métis” confirmeraient cette analyse (6). A coté des facteurs génétiques qui sont indéniables (facteurs de susceptibilité), il apparaît indiscutablement le rôle “protecteur” de certains facteurs environnementaux chez le noir africain. NEUROEPIDEMIOLOGY OF KONZO A SPASTIC PARA-TETRAPARESIS OF ACUTE ONSET IN A NEW AREA OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGOABSTRACT Background Method Results Conclusion Mots clés : manioc, konzo, paraparésie spastique aigue, substances cyanogènes RESUME Description Objectif Methode Resultats Conclusion Keywords: acute spastic paraparesis, cassava, cyanogens exposure, konzo INTRODUCTION Spastic paraparesis has been documented both in local outbreaks and in endemic areas in different geographical areas of the world. Various factors have been associated with these epidemics or endemics; for instance, the retrovirus Human Tlymphotropic Virus, type I (HTLV-I) in HTLV-I-associated myelopathy (HAM)(1,47), the over-consumption, with a restrictive diet, of the grass-pea (Lathyrus Sativus) in lathyrism (5,12) and the consumption of insufficiently processed bitter cassava with a low intake of sulfur amino acids in konzo (11). A syndrome called tropical ataxic neuropathy (TAN) has also been associated with the consumption of insufficiently processed bitter cassava, though it has been clinically connected with predominantly sensory disturbances(10). In 1996, we made a neuroepidemiological study of an outbreak of a spastic paraparesis, suspect of konzo, in Bandundu province of the Democratic republic of Congo (DRC). The aim of the study was to determine if this outbreak was compatible with konzo, and to investigate if the disease was associated to the same possible causal factors as in previous studies in other parts of Africa. MATERIAL AND METHODS Study area Bandundu Province, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, is situated southeast of the capital Kinshasa (2°-8° south and 16°-20° east). It covers 295,000 km2 with a population of 3.7 million in 1984, according to national demographic statistics (6). Popokabaka Health Zone is located in the southwestern part of this province. It consists of a savanna tableland with poor sandy soils intersected by forested, relatively more fertile river valleys running in roughly south-north. The population lives mainly in villages, growing cassava as their major subsistence and cash crop. Due to a reported high prevalence of the disease at Masina Health Center, we selected the Masina catchment area (14 x 14 km), situated 90 km east of Popokabaka township as the study area (Fig.1). Methods The study was done in August 1996. With informed consent and assistance from village leaders, a demographic census was performed in all 11 villages in the area. The inhabitants were registered according to ethnic affiliation, sex, and age group (children <15 years, adults ³15 years). The population in each village was screened for konzo by examining all persons with walking difficulties identified by village leaders or health staff. The WHO criteria for konzo (15) were applied: a visible symmetric spastic abnormality when walking and/or running, a history of abrupt onset (< 1 week), a non-progressive course, in a formerly healthy person, showing bilaterally exaggerated knee and/or ankle jerks without signs of spinal disease. Those fulfilling the criteria for konzo were interviewed in Kiyaka, the local language, according to a standardized questionnaire regarding the time of onset and the diet at onset. Information on year of onset was cross-checked with dates on birth certificates available for neighboring children. Month of onset was determined by use of a local event calendar. Thereafter, konzo-affected persons were invited for a detailed neurological examination by a neurologist (D.T.) including evaluation of higher cerebral functions, as well as an evaluation of the cranial nerve function, and of motor, sensory, autonomic and cerebellar functions. The severity of the disease was graded according to the WHO classification (15) (mild form = walking without support, moderate form = using one or two sticks, severe form = unable to walk). Other clinical signs were recorded and the size of the thyroid gland assessed according to the new WHO classification (16): grade 0 = no goiter, grade 1 = palpable goiter, grade 2 = visible goiter. Konzo subjects who had died were traced and characterized through interviews with the nurse at the Health Center, relatives and neighbors. Focus group interviews (3) with 5-9 adult participants of mixed ages were performed in the nine largest villages. A set of open questions was introduced concerning the village, seasonal and annual variations in agriculture, cassava processing, cassava marketing, diet, and konzo, a well-known disease in the area. A new semi-quantitative field assay for urinary thiocyanate was developed and used to screen 20-30 urine samples in each village, for thiocyanate content. This new method is a modification of the previous thiocyanate method (8) suitable for field surveys and yielding immediate semi-quantitative results. It distinguishes ordinary concentrations (below 100 µmol/L) from elevated levels (above 300 µmol/L). A blood specimen and spot urine samples were collected from examined konzo patients. Specimens were analyzed at the Department of Clinical Chemistry at Uppsala University Hospital in Sweden. Serum was analyzed for prealbumin, albumin, C-Reactive Protein, creatinine and thiocyanate (8). Urine was analyzed for linamarin (2), thiocyanate (8) and sulfate (9). Serum and urinary thiocyanate and urinary linamarin served as indicators of cyanogen exposure, whereas albumin, prealbumin, and sulfate served as protein status indicators. Virological tests for HIV 1-2 (Behring ELISA) and HTLV I-II antibodies (ELISA/Wellcome) were carried out at the Department of Microbiology, Uppsala University Hospital. RESULTS The Masina Health Center catchment area consists of 11 villages with, in august 1996 a total of 490 households and 2,723 inhabitants (551 men, 755 women, 714 boys <15 years and 703 girls <15 years), giving a mean of 5.5 persons per household. The number of inhabitants in each of the 11 villages is given in Fig.1. Yaka was the only ethnic group in the area. Occurrence of konzo Of 152 persons with walking difficulties, 55 fulfilled the criteria of konzo, thus a prevalence of 20 per thousand inhabitants in the study area. The remainder (97/152) had disabilities of various other origins: pain in the joints of lower limbs (92), psychosomatic disorder (2), possible disk hernia (1), myositis (1), and foot injury (1). A typical history of konzo was also obtained for another 27 named persons, 12 of whom had moved to neighboring villages outside the catchment area or to the capital, Kinshasa. Two of these were visited in their homes in Kinshasa for interview and examination. The other 15 were deceased. Of the 82 persons thus identified as being affected by konzo, 20 were boys below 15 years of age at the time of onset, 23 were girls, 7 men aged 15 years or more, and 32 women aged 15 years or more. The age and sex distributions are presented in Fig. 2. The annual and monthly distributions of the onset of konzo are shown in Fig. 3 and 4, respectively. Clinical findings Symptoms at onset of konzo

Table 1 shows the motor findings in relation to the severity of konzo. All subjects had decreased muscle power in the extensors of the lower limbs. Two of the seven subjects severely affected by konzo had tetraparesis. Tendon reflexes were exaggerated in the lower limbs in 42 patients (74%), while in the remainder the reflexes were difficult to elicit due to joint contractures or ankylosis. Ankle clonus was found in 40 cases (70%) and was similarly difficult to elicit in the remainder. Babinski’s sign was found in 34 subjects (60%) and no response in the remainder. All patients except 6 (11%) with joint contractures, had symmetric clinical signs in their limbs. Ten subjects (18%) lacked cutaneous abdominal reflexes. Eight subjects (14%) presented a bilateral palmomental reflex. Speech problems of dysarthric type were found in 14/57 patients (25%) with either the moderate or severe form of konzo. Thirteen subjects (23%) with either mild, moderate, or severe konzo reported impaired visual acuity at the onset of the disease. Rotatory nystagmus was observed in 3 subjects (5%) with onset at 2, 8 and 12 years of age, having a mild or moderate form of konzo. One 11-year-old subject showed mental and physical retardation and had spastic tetraplegia with bilateral palmomental reflex and Babinski’s sign. He had contracted the disease 4 years earlier, in its mild form, but had two abrupt aggravations, one 3 years after the onset and the other 6 months before the study. Subsequently and simultaneously he lost the ability to walk, to speak and to swallow. He was still unable to walk at the time of the study. No cerebellar dysfunction was found in the patients. Sensory disturbances (touch, pain, position, and vibration) or autonomic symptoms (such as disturbance of urethra – and/or anal sphincter and sexual functions) were not found or reported, except for paresthesia and the sensation of electrical discharges in the lower limbs at onset. Other clinical signs Distal amyotrophy in arms and/or legs was found in 4 subjects (7%), and lumbar kyphosis in 3 cases (5%). Thirty-six patients (63%) had goiter; of these 27 (47%) had grade 1 goiter and 9 (16%) grade 2. Various signs of malnutrition (discolored hair, skin desquamation, edema) were found in 7 cases (12%). The diet The focus groups revealed that people relied on bitter cassava as their staple diet. Shortcuts in the processing of cassava roots are common – e.g. usually only 2 nights of soaking. Especially since 1992, shortcuts in processing had become common as a result of the intensive trade in cassava to Kinshasa. All the konzo patients ate the traditional cassava-flour based dough every day as staple. Cassava leaves were the most commonly eaten supplementary food. Meat and fish were not yet eaten daily in the villages. Lathyrus Sativus was not known at all or seen in the area. Laboratory findings Urinary thiocyanate testing by the semi-quantitative method in 213 randomly selected villagers in the area showed that 160 (75%) of the urine samples contained thiocyanate more than 300 µmol/L. Of the 38 blood samples, all proved negative to all four tested retroviruses (HIV-1, HIV-2, HTLV-I and HTLV-II). Creactive Protein was normal in all except one who had a slight increase (21 mg/L). The mean concentration of albumin was 28 (±5) g/L, all except one below the reference value of 40-52 g/L; of prealbumin 0.2 (±0.05) g/L, 28 of 38 patients being below the reference value of 0.225 g/L. The mean (±SD) concentration of thiocyanate was 502 (±153) mmol/L. Serum creatinine was clearly elevated (>100 mmol/L) in 21 of the 38 subjects, the range being 42-280 mmol/L. DISCUSSION This outbreak shared many characteristics with those previously described in Bandundu. Age and sex distributions and the seasonal variation are similar to those in earlier reports (11). The interview findings also confirm that the population in this area is using short-processed bitter cassava and that this short-processing has become more common as a consequence of intensified trade in cassava to Kinshasa. The high concentrations of thiocyanate in the urine of the general population confirm that the consumption of short-processed cassava exposes the people to dietary cyanogens. The main clinical sign of konzo is a spastic paraparesis, as previously described in several studies(11). The disease has a sudden onset, starting mainly with trembling in the legs. The handicap remains irreversible and may be exacerbated by further attacks, leading to severe disability. The disease is sometimes associated with other symptoms related to cranial nerve involvement (visual impairment) and/or pseudobulbar signs (speech or swallowing difficulties). Most subjects show a symmetrical clinical picture, except when joint contractures or ankylosis are present. The proportion of neurological signs increases with the severity of konzo. This involves mainly the addition of abnormalities in the upper limbs (increased tendon reflexes and /or decreased muscle power), leading to tetraplegia in severe cases. In this respect konzo shares similarities with the spastic diplegia of cerebral palsy. The nystagmus found in 3 subjects (5%) with onset at 2, 8, and 12 years of age raises the question whether it should be considered a sign of konzo. This symptom might be of clinical importance, since it has also been described in 2 patients with konzo in the Central African Republic (14). The palmomental reflex has not been reported in previous studies. Although it might support brain dysfunction, it is known that it can occur in healthy subjects in the general population. The mental retardation, found in one patient, raises the question whether konzo also affects mental capacity. Indeed, this subject lost his mental faculties as soon as he experienced two further attacks of konzo, which exacerbated his motor disability. On the other hand, this patient might have had an initial encephalopathy, and konzo could have impaired his condition further, or vice versa. Other clinical signs such as amyotrophy and lumbar kyphosis are associated with konzo. A central motor neurone dysfunction can lead to amyotrophy, whereas the typical toe-walk with knee flexion of konzo subjects can result in kyphosis as a compensatory phenomenon. The high proportion of goiter (63%) raises the question whether clinical signs of Iodine Deficiency Disorders (IDD) might be associated with konzo and make unclear, to some extent, the pathogenesis of certain symptoms, for example in case of mental retardation or nystagmus. The increased serum creatinine level has not been reported earlier and could be related to the fact that water was very scarce in the study area. Consequently, the low hydration of subjects might explain the high values observed, but this needs to be further evaluated. Laboratory findings demonstrated high cyanogens exposure in connection with low protein intake and the absence of retroviruses antibodies, as found in previous konzo study areas (11,13). Cyanogenic glucosides and their metabolites are therefore once again linked to konzo.

Table 1 : Motor findings in relation to severity of konzo

Table 2 : A subset of neurological symptoms found in relation to the severity of konzo

Figure 2

Figure 4

ABSTRACT Background Objective Methods Results Conclusion Keywords : cerebrospinal fluid, intracranial brain abscess, lumbar puncture, subdural empyema RESUME Introduction Objectif Méthodes Résultats Conclusion Mots clés : abcès intracrânien, empyéme sous-dural intra-crânien, liquide cérébro-spinal, ponction lombaire INTRODUCTION Computed tomography (CT) was first introduced in South Africa at the neurosurgical unit at Wentworth Hospital, Durban in 1975, and despite it’s increasing availability, lumbar puncture (LP) appears still to be commonly performed in our region as a first diagnostic procedure in patients with brain abscess or subdural empyema. In a 15-year review of patients with brain abscess and subdural empyema treated at our institution between 1983 and 1997, nearly a third had undergone a diagnostic lumbar puncture prior to CT. We therefore evaluated the diagnostic role of lumbar puncture in these patients as well as it’s impact on patient outcome. PATIENTS & METHODS During the 15-year period, January 1983 to December 1997, patients with brain abscess and subdural empyema admitted to our neurosurgical unit were evaluated. The neurosurgical unit at Wentworth Hospital in Durban is the sole referral centre for the Province of KwaZulu-Natal and half of the Eastern Cape Province. The diagnosis of brain abscess or subdural empyema was made on conventional CT criteria in all cases and definitively at surgery in almost all (97.8%) [1, 23]. The investigative procedures which these patients underwent were retrospectively reviewed. Patients undergoing diagnostic lumbar puncture prior to CT were identified and their case notes were carefully analysed with respect to the contribution of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis to diagnosis and to the impact of lumbar puncture on outcome. RESULTS During the 15-year period, a total of 4623 patients with all forms of intracranial infection were admitted to our neurosurgical unit at Wentworth Hospital in Durban, South Africa. Of these, 1411 patients were diagnosed as harbouring purulent infective intracranial mass lesions, in particular 712 with brain abscess and 699 with subdural empyema. One hundred and forty-two of these 712 patients with brain abscess (19.9%) and 280 of the 699 patients with subdural empyema (40.1%) had undergone diagnostic lumbar punctue prior to CT and, importantly, prior to referral to our unit. Overall, 422 patients (29.9%) were subjected to lumbar puncture as the first diagnostic procedure, prior to CT. [Table 1] CSF analysis from lumbar puncture revealed a normal CSF in 66 patients (15.6%), bacterial meningitis in a minority 73 (17.3%) and a pleocytosis in 283 (67.1%). In the latter case bacterial meningitis could not be proven and an organism could not be cultured. Typically, the CSF in such a situation revealed white cell counts < 500/cm3 with a predominance of polymorphs, an elevated protein level and, either normal or moderately depressed CSF glucose levels. Overall, therefore the CSF examination was either normal or non-diagnostic in 349 patients (82.7%). An organism was cultured in 42 of the 422 patients (10.0%) and this was predominantly in the group of infant patients with subdural empyema secondary to bacterial meningitis (83.3%). Of great concern and of significance the CSF pressure was only measured in 25 patients (5.9%) and when measured was raised (>20cm) in 15 (60%). [Table 2] As might have been expected 272 patients (64.5%) experienced clinical deterioration (drop in Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) or development of a new focal sign) at some time following lumbar puncture. However, only in 81 patients (19.2%) could the deterioration predominantly be attributable to lumbar puncture. Twenty of the 81 patients died (4.7%). The fatalities predominantly occurred in patients with abscesses (hemispheric in 10 and cerebellar in 7). In the case of subdural empyema only three cases existed. [Table 3] DISCUSSION Many authors, including one of the present group [18] have strongly cautioned against the performance of lumbar puncture in patients with suspected or likely infective intracranial mass lesions due to the dubious value of the CSF analysis so obtained, and due to the inherent danger of clinical deteriorationprecipitated by a pressure cone [6-10,12,13,20-22]. The diagnostic value of CSF findings from lumbar puncture have proved to be limited. Carey et al found that approximately one-third of patients with proven brain abscess did not show any significant CSF pleocytosis, two-thirds had elevated protein levels, and glucose levels were lowered in one-quarter [3]. Gregory et al noted that in three-quarters of brain abscesses, the CSF glucose level was normal, while Yang in an authoritative series of 400 brain abscesses reported that the CSF white cell count was not necessarily elevated, being < 10/mm3 in 21% of cases [21, 22]. Kratimenos et al in a series of 14 patients with multiple brain abscesses noted that the CSF obtained by lumbar puncture did not yield any positive cultures [14]. Galbraith et al and Kaufman et al reported similar findings regarding CSF analysis in patients with subdural empyema [9,13]. It has been proposed that the arachnoid is a significant, hardy layer that protects the CSF from the subdural, extra-arachnoidal collection of pus in patients with subdural empyema. In patients presenting in a delayed fashion, the CSF may however exhibit an equivocal neighbourhood pattern due to prolonged contact of the pus with the arachnoid leading to arachnoiditis with resultant CSF changes .[9, 13] In our series of 422 patients, CSF examination was normal or non-contributory in over 80% of cases. It has been our alarming experience that a normal or equivocal CSF examination often lulls the referring physician into complacency, who then treats the patient as one with viral meningitis or partially treated bacterial meningitis, leading to a delay in diagnosis and appropriate treatment. The dangers of lumbar puncture in patients with infective intracranial mass lesions have been well documented by many [8,9,10,12,13,18]. Gregory (1967), Duffy (1969) and Garfield (1969) have all described clinical deterioration following lumbar puncture[8,10,12]. Garfield described deterioration in the level of consciousness in the ensuing 48 hours in 41 of 140 patients who underwent lumbar puncture [10]. Carey could attribute the deaths of 5 patients (5%) to lumbar puncture. [3] Chun et al described the death of 4 of 27 patients (14.8%) who died within 24 hours of undergoing lumbar puncture [5]. Large series of patients with brain abscess or subdural empyema undergoing diagnostic lumbar puncture have previously been reported. In 1960, Bonnal et al reported 208 cases and, more recently, Yang reported 173 cases [21,22]. Both authors cautioned that lumbar puncture was of limited value and was hazardous. In our series, 20 deaths could be directly attributed to lumbar puncture (4.7%). Seven of the deaths were in patients harbouring cerebellar abscesses where supratentorial hydrocephalus has been documented as a concomitant adverse prognostic factor. [15] One of the 14 patients with infratentorial subdural empyema also died. Associated supratentorial hydrocephalus probably also being a contributory factor in the precipitation of the pressure cone [16]. In addition to pressure cone, lumbar puncture may rarely also precipitate intracerebral or subdural haemorrhage [17,19]. We support the view of Ciarallo et al who cautioned against injudicious lumbar puncture in patients with periorbital cellulitis [4]. We also concur with Garfield who advised that a lumbar puncture should not be performed in patients with meningeal irritation when a convulsion has occurred, or if papilloedema, hemisphere or cerebellar signs are present [10]. Gower et al have recently described contra-indications to lumbar puncture as defined by CT, which would support the clinical view [11]. In addition to Garfield's contra-indications to performance of lumbar puncture, we would recommend that a patient with meningeal signs and who also exhibits evidence of trauma, sinusitis or mastoiditis not undergo lumbar puncture but should rather be firstly investigated by CT. In the absence of readily available CT facilities, we strongly recommend that such a patient be commenced on empirical, highdose, intravenous antibiotics until such time that a CTis obtained. CTis becoming an increasingly accessible modality in our region, with 8 public sector CTscanners already installed in the Province of KwaZulu-Natal, with 6 teleradiologically linked to Wentworth Hospital. Our report of 422 cases, which also represents the largest series reported to date, supports the view that lumbar puncture is of limited use in diagnosis of brain abscess and subdural empyema and, more over, is inherently dangerous and therefore students and practitioners should be advised, and taught, on the dangers. It is hoped that with the ever increasing availability of CT, the iatrogenic conversion of a patient with an eminently treatable brain abscess or subdural empyema into one with secondary irreversible brainstem damage from pressure cone could be avoided [8]. TABLE 2 : CSF ANALYSIS IN 422 PATIENTS UNDERGOING LUMBAR PUNCTURE

TABLE 3 : CLINICAL DETERIORATION FOLLOWING LUMBAR PUNCTURE IN 422 PATIENTS

Articles récents

Commentaires récents

Archives

CatégoriesMéta |

© 2002-2018 African Journal of Neurological Sciences.

All rights reserved. Terms of use.

Tous droits réservés. Termes d'Utilisation.

ISSN: 1992-2647