|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

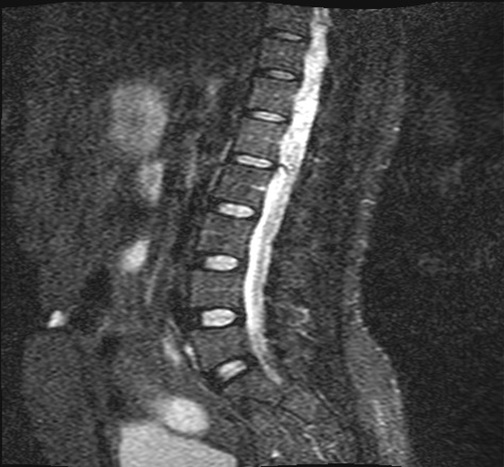

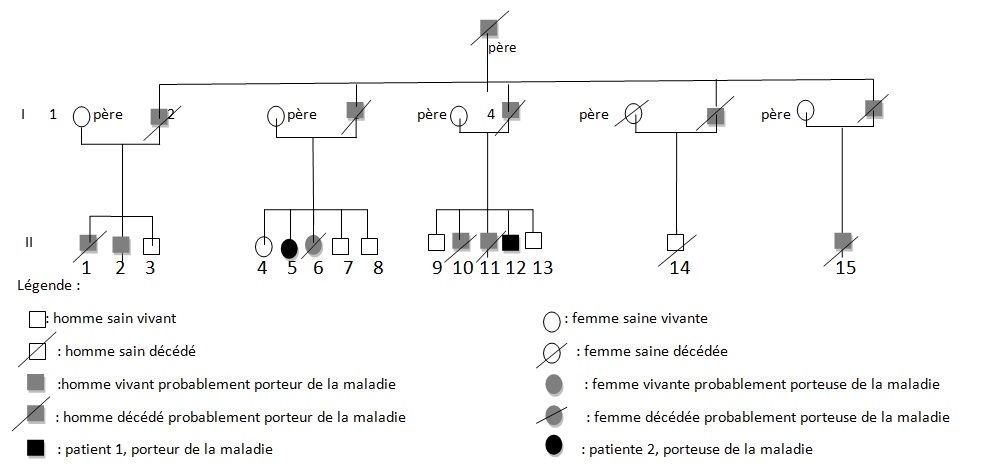

RESUME La maladie de Von Hippel Lindau(VHL) est une affection héréditaire autosomique dominante dont l’expression phénotypique est variable et multiviscérale. Le diagnostic nécessite des arguments cliniques et un plateau technique de pointe. nous rapportons les résultats d’une enquête au sein d’une famille togolaise à partir de deux observations cliniques. Ces observations mettent en exergue les difficultés de la pratique médicale en Afrique subsaharienne liées à un plateau technique inexistant. SUMMARY Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is an inherited disorder characterized by the formation of tumors and fluid-filled sacs (cysts) in many different parts of the body. The diagnose of this affection need a clinical and technical update materials. From two observations, we report outcome of a Togolese family. INTRODUCTION La maladie de Von Hippel Lindau(VHL) est une affection héréditaire autosomique dominante dont l’expression phénotypique est variable et multiviscérale. Elle est caractérisée par le développement de tumeurs vasculaires (« hémangioblastomes ») touchant avant tout le cervelet (à l’origine de céphalées, de nausées et de vomissements traduisant une hypertension intracrânienne), la moelle épinière et la rétine [15]. Il s’y associe des tumeurs des reins, du pancréas, des surrénales, à l’origine des phéochromocytomes, et du sac endo lymphatique de l’oreille interne à l’origine des cystadénomes du ligament large et de l’épididyme [16]. La découverte d’un hémangioblastome rétinien ou du système nerveux doit faire rechercher une lésion viscérale et vice-versa. Un diagnostic précoce est important non seulement pour le malade, mais cela permet aussi de rechercher l’affection dans la famille de ce malade .Elle touche les deux sexes et atteint environ 1 personne sur 40.000 [2]. OBSERVATION N°1 Mlle A.K.M., de race Noire, togolaise célibataire de 33 ans exerce une activité de commerce et a des antécédents familiaux de décès paternel jeune d’une HTA difficilement contrôlable. Elle est 5e d’une fratrie de 15 enfants dont 6 décédés de cause inconnue. Les antécédents personnels sont représentés par : un phéochromocytome surrénalien bilatéral avec résection en 1984 et 1990 à l’hôpital cantonal de Genève, une hystérectomie subtotale en 2006 à Lomé pour multiples fibromyomes utérins, des séquelles d’onchocercose oculaire bilatérale, une rétinopathie hypertensive, une insuffisance surrénalienne lente et un diabète cortico induit. Elle est sous metformine et hydrocortisone. Elle a consulté pour faiblesse progressive des deux membres inférieurs en avril 2004 pour difficultés croissantes à la marche, et sensation de faiblesse des membres inférieurs prédominant à droite associé à des troubles de la miction (doit appuyer sur la vessie pour uriner) et de constipation. L’examen clinique retrouvait : un état de conscience normal, une bonne orientation spatio-temporelle, une force musculaire aux membres inférieurs cotée à 4/5 sur tous les groupes musculaires, un niveau sensitif supérieur à D11, une hyper réflexie du membre supérieur droit, une hyper réflexie rotulienne et achiléenne, signe de Babinski bilatéral, une diffusion des régions réflexogènes rotuliennes droites et un clonus achilléen bilatéral. Il n’y avait pas d’incontinence urinaire. Devant ces signes une IRM a été faite à Lomé, révélant de multiples lésions intradurales et extramédullaires, motivant son transfert à l’hôpital Cantonal de Genève en neurochirurgie pour une prise en charge spécialisée. A l’ HUG Cantonal, l’IRM cérébrale et spinale ne notait pas de lésion intracérébrale. En T1 (figure 1) les lésions étaient hypointenses avec important réseau vasculaire associé. En T2, l’examen spinal a mis en évidence trois (03) lésions intracanalaires extramédullaires situées aux niveaux C5-C7 (figure 2), D9-D10 (figure 3), D12-L1 (figure 4), comprimant la moelle surtout au niveau D9-D10 prenant fortement le contraste et hyperintenses (figure 5), La scintigraphie au MIBG montrait de multiples masses hypervasculaires, intraspinales avec absence de captation au niveau des masses connues intraspinales, en 24 heures après injection. L’angiographie médullaire montrait une lésion cervicale vascularisée par des branches directes de l’artère vertébrale droite, cervicale profonde droite et cervicale ascendante droite. La lésion présente des shunts rapides et un drainage veineux à partir des veines médullaires et para spinales. Cette lésion pouvait être embolisée par voie endovasculaire. La lésion thoracique était vascularisée par des branches spinales méningées D12 droite, D11 droite, radiculo-médullaire postérieure gauche, D8 gauche. La lésion thoraco-lombaire était vascularisée par une branche méningée D11 gauche et une radiculo-médullaire antérieure L2 gauche. Le test génétique a permis de retrouver une mutation hétérozygote dans l’exon 1 du gène VHL : mutation p.Tyr98Cys déjà rapportée. Finallement, le diagnostic d’une compression médullaire cervicale C5-C7, dorsale D9-D10 et dorso-lombaire D12-L1 par des hémangioblastomes a été retenu. Il a été réalisé une embolisation de la lésion cervicale suivie d’une résection macroscopiquement totale des trois hémangioblastomes postéro-latéraux droits après une laminotomie ostéoplastique thoraco-lombaire ; le plus gros en position inférieure D12-L1, mesurant 31 mm) Une ablation également macroscopiquement totale d’un hémangioblastome supérieur situé en D9-D10, antéro-latéralement à la moelle du côté gauche a été également réalisé. L’évolution immédiate a été marquée par une paraplégie ASIA C avec niveau sensitif supérieur D7 et des troubles sphinctériens urinaires. Un traitement anti-cholinergique avait permis de retrouver une miction normale et une physiothérapie intensive avait permis de retrouver une marche avec cannes (périmètre de marche 500 mètres) en 20 jours. L’évolution ultérieure était favorable et avait permis la mise sous cortisone 25 mg et Fluorohydrocortisone 0.05 mg par jour, à vie. L’examen ophtalmologique a été normal. On a noté une absence de tumeur thoraco-abdomino-pelvienne à la TDM et une MAPA en faveur d’une HTA limite et labile. L’IRM cérébrale était normale. OBSERVATION N°2 Mr A.K., de race Noire Togolais, 21 ans célibataires sans enfants, étudiant en économie, aux antécédents familiaux de décès paternel jeune d’une HTA difficilement contrôlable, douzième d’une fratrie de 15 enfants dont 6 sont décédés de cause inconnue et également le frère cadet de la patiente 1, de mère différente. Les antécédent personnels sont les suivants : un phéochromocytome surrénalien droit et tumeur retro cave droite reséqués en 1988 ; un accident vasculaire hémorragique (AVCH) capsulo lenticulaire droit en 1999 avec pour séquelle une hémiparésie gauche proportionnelle et rétinopathie hypertensive, non classée. Il a consulté pour masse abdominale et une HTA. Le début remontait au mois de janvier 2001, par le développement rapidement progressif d’une masse abdominale associée à une HTA difficilement contrôlable. L’examen clinique révélait : un bon état général, les conjonctives étaient colorées anictériques, une absence d’dème des membres inférieurs. Une cicatrice abdominale médiane indolore, un abdomen souple, indolore, sans hépatosplénomégalie ni adénopathies palpables. Les bruits intestinaux étaient normaux. On pouvait palper une masse, ferme, indolore localisée dans la loge rénale droite. une suspicion de récidive de phéochromocytome a été évoquée et le patient a été transféré à l’hôpital cantonal de Genève pour une prise en charge spécialisée. Les examens para cliniques (réalisé à HUG cantonal) ont montré : TH = 10,1 g/L ; hématocrite = 29.7% ; glycémie, natrémie, kaliémie, chlorémie, urémie, créatininémie et protéinémie normaux. La biologie urinaire retrouvait: noradrénaline = 8 404nmol/j (28xNormale) et vanilmandelate = 84 umol/j (3xNormale) élevées. L’adrénaline, la dopamine et les métanéphrines étaient normaux. Le sodium, le potassium, le calcium, les phosphates, et l’urée urinaires étaient également dans les normes. La radiographie du thorax était normale. L’IRM cérébrale visualisait des séquelles de ramollissement hémorragique capsulo-lenticulaire droit avec discrète dégénerescence valérienne et atrophie sous-corticale en regard. La TDM thoraco abdominale montrait une importante masse surrénalienne droite avec absence de la glande surrénale gauche. On notait également la présence d’une masse rétrovésicale. La scintigraphie au MIBG mettait en évidence d’une récidive plurifocale d’un phéochromocytome (1 en projection de la loge surrénalienne droite, 2 foyers péri-aortiques, 1rétrovésical). La Tomoscintigraphie PET avait permis de mettre en évidence 02 masses, hypermétaboliques, correspondant aux localisations les plus captantes à la scintigraphie à la MIBG à savoir: la région surrénalienne droite et para rectale gauche. Le caractère nettement hyper métabolique de ces foyers ne permettait pas, sur la base de l’expérience de ce traceur dans cette indication, de prédire la présence ou à l’absence de malignité. A l’ECG on retrouvait une hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche avec indice de Sokolow positif, une onde T inversée en D III, AVR et AVF et un segment ST ascendant de V1 à V2. L’échographie cardiaque était normale. L’examen ophtalmologique observait une rétinopathie hypertensive. Le diagnostic d’une récidive de phéochromocytome avec un foyer surrénalien droit, 02 foyers paraspinaux et 01 foyer rétrovésical a été retenu. Il a été institué un traitement alpha-bloquant puis beta bloquant contre l’HTA, suivi d’une exérèse complète des tumeurs, le 13 mars 2001, par voie chirurgicale thoraco-abdominale. L’évolution a été favorable, sans complications. Le patient a été mis sous cortisone 25mg et Fluorohydrocortisone 0.05 mg par jour, à vie. Au cours du suivi ultérieur, on a noté un examen ophtalmologique normal, une absence de tumeur thoraco- abdomino-pelvienne et la MAPA a révélé une HTA limite et labile. L’enquête familiale faite dans des conditions très difficiles nous a néanmoins permis de dresser l’arbre généalogique (figure 6).  Figure 1  Figure 2  Figure 3  Figure 4  Figure 5 DISCUSSION Notre observation a reposé sur l’anamnèse familiale, l’histoire de la maladie des deux membres traités et l’examen clinique du reste de la famille. Nos conclusions ne peuvent pas être affirmatives quant à la réalité de la mutation chez les autres membres de la famille. Nielsen SM et al avaient effectué une étude similaire à partir de l’anamnèse familiale, du test génétique et de la caractérisation phénotypique de chaque membre [11]. Notre observation est la première du genre à propos de la maladie de VHL décrite au Togo. L’âge de découverte de la maladie était en moyenne de 29 ans, parce que c’est à la deuxième manifestation de la maladie (récidive de phéochromocytome pour l’un et HB spinal pour l’autre) que le diagnostic a été évoqué.  Figure 6 Le délai du diagnostic après les premiers signes de la maladie est estimé à une moyenne de 18.5 ans. Nous avons noté une égalité d’atteinte entre femme et homme, ce qui ne nous permet pas de tirer une conclusion car le nombre de patients de notre étude n’était pas significatif. Pavesi et al avaient retrouvé 35% de femmes atteintes pour 65% d’hommes au sein d’un groupe de 20 patients étudiés [14]. Nos patients étaient de race noire et de nationalité togolaise, à notre connaissance, seul un cas africain a été décrit par Naidoo en 1998 en Afrique du Sud, à propos d’une femme atteinte de multiples HB découverts au cours de la surveillance d’une grossesse [9]. Des cas de maladie de VHL ont été décrits dans les autres races surtout blanche. Les deux patients de notre observation avaient pour première manifestation un phéochromocytome découvert à un âge moyen de 10.5 ans superposable aux résultats d’Hammond et al avec à un âge moyen de 13 ans [5]. Notre patiente numéro 1 avait une atteinte bilatérale des surrénales. Notre patient numéro 2 a développé une récidive de phéochromocytome avec localisation extra surrénale à 21 ans soit 13 ans plus tard et l’autre, de multiples HB spinaux qui ont été découverts à l’âge de 37 ans soit 24 ans après le phéochromocytome. Ces évènements rappellent les études d’Opocher G et Schiavi F qui concluaient que la première cause de phéochromocytome associée aux paragangliomes est la maladie de VHL [13]. Nous n’avons retrouvé que deux types de lésions à savoir, dans l’ordre, le phéochromocytome et l’HB spinal. Nakaji S et al décrivaient le cas d’un patient de 40 ans porteur d’une mutation du VHL et également porteur de multiples tumeurs du pancréas et d’une tumeur rénale [13]. Il semblerait que parmi les lésions les plus fréquentes figurent les HB avec diverses localisations; ainsi en témoigne la présence d’HB spinal, retrouvé chez la patiente numéro 1. Il n’est pas rare que ces HB se présentent en de multiples foyers d’atteintes comme ceux observés chez notre patiente (cervical, dorsal, et dorsolombaire). Pavesi et al retrouvaient cervelet (42%), spinaux (38%), SNC (18%) et sac endolymphatique (2%) [14]. Les modes d’expression de la maladie sont multiples. Notre enquête familiale avait permis de retrouver que tous les 06 membres de la famille, que nous avons examiné, étaient porteurs d’une HTA plus ou moins labile, sans tumeur TAP avec une anamnèse familiale retrouvant une notion de HTA sévère ayant conduit au décès de 06 /16 membres de la famille. Le test génétique est le seul examen permettant d’affirmer l’existence de la maladie. Il aurait du être pratiqué chez notre patiente numéro 1 dès la découverte du phéochromocytome bilatéral. Cependant, la pratique du test génétique n’est pas systématique. A la suite de la deuxième atteinte, spinale, un test génétique a été réalisé chez notre patiente numéro 1, qui avait retrouvé une mutation du gène VHL rapportée comme étant une mutation p.Tyr98Cys décrite par Gallou [3]. Les autres modifications du gène ont été récapitulées par Nordstrom-O’brien [12]. A ce jour, nos patients âgés de 40 ans pour la patiente numéro 1 et de 31ans pour le numéro 2, sont vivants. Les deux présentent des séquelles neurologiques liées aux manifestions de la maladie, graves pour le patiente numéro 1 et minime pour l’autre. En ce qui concerne le risque de développer de nouvelles lésions à partir de 60 ans, Pavesi et al[14], ont trouvé pour l’HB du cervelet 84%, pour l’HB de la rétine 70%, et pour le cancer rénal de 69%. La moyenne d’âge de survie pour ces patients atteints de la maladie de VHL était de 49 ans, le cancer rénal étant la première cause de décès [14]. Nos deux patients ont eu une surrénalectomie bilatérale par laparoscopie en Suisse pour phéochromocytomes non malins. Le deuxième patient avait développé une récidive à 21 ans (soit 13 ans après) avec localisations extra-surrénales et surrénale controlatérale. Les deux patients sont cortico-dépendants et la permière patiente a développé un diabète cortico-induit. Pour Benhammou et al après 36 surrénalectomie, 11% des patients ont développés une récidive au même endroit, 11% récidivaient sur la surrénale controlatérale et seul 11% des patients étaient devenus cortico-dépendants, avec une médiane de survie de 9,25 ans [13]. La première patiente a été prise en charge en neurochirurgie pour des hémangioblastomes (développés 24 ans après le phéochromocytome) spinaux avec des séquelles une paraparésie, sans récidives. Pavesi et al [14] relevaient que 5% des patients après une intervention neurochirurgicae n’avaient pas eu une résection complète (confirmation par IRM), 75% avaient eu une amélioration de leur état neurologique, 20% avaient été stabilisés et 5% avaient eu une aggravation [14]. Une alternative à la chirurgie serait la radiochirurgie stéréotaxique, mais les résultats restent discutés [14]. Nos deux patients n’ont effectué aucune visite médicale dans le cadre du suivi de leur maladie, ceci pourrait être dû au fait qu’un plan de surveillance n’avait pas été établi à l’avance et à un manque de moyens financiers. Lammens et al ont noté que 1/4 à 1/3 des patients ne respectait pas le plan du suivi médical proposé [6]. De nos deux patients aucun n’a eu des enfants à la suite du conseil génétique effectué au cours du traitement de leurs phéochromocytomes en Suisse. Lytras A et Tolis G [7] ont décrit l’existence des troubles de la reproduction chez les patients VHL, notamment dus à des kystes du mésosalpinx, des cystadénomes du ligament large et des calcifications des cellules de Sertoli. Les autres membres de la famille, bien qu’étant au courant des risques de transmission, ont des enfants et des petits-enfants, pour lesquels il serait pertinent de réaliser une enquête. CONCLUSION Notre travail a porté sur l’observation clinique de deux cas de la maladie révélés par un phéochromocytome et associé à une enquête familiale. Ce travail relève les difficultés auxquelles les recherches sont confrontées en Afrique en raison de l’ignorance des populations (connaissance partielle de l’histoire familiale par les membres de la famille, absence de dossier médical bien tenu en possession des patients concernés), du manque de moyens financiers et de l’absence de moyens d’investigations (tests génétiques, IRM, dosage des catécholamines urinaires, audiométrie). Il nous a également permis de réaliser que des cas africains de la maladie de Von Hippel Lindau existent, et une investigation plus approfondie de la famille pourrait permettre d’envisager une prévention des complications possibles et une élaboration d’un canevas de suivi plus adapté. Cette étude devrait être complétée par d’autres études prospectives pour déterminer une prévalence au sein de la population africaine et togolaise en particulier. Ce travail devrait être complété par d’autres études prospectives sur la prévalence réelle des maladies génétiques au Togo.

RESUME Le but de notre étude était d’évaluer, en l’absence d’une rééducation neuropsychologique, l’impact du syndrome de l’hémisphère mineur sur le devenir fonctionnel des patients hémiplégiques gauches après un accident vasculaire cérébral. Il s’agit d’une étude longitudinale réalisée dans deux centres de rééducation fonctionnelle à Brazzaville, du 1er décembre 2011 au 1er Octobre 2012. L’étude a consisté à suivre pendant 6 mois, deux catégories de populations d’hémiplégiques gauches après un premier AVC, avec vs sans troubles gnosiques entrant dans le cadre du syndrome de l’hémisphère mineur. Tous les patients admis pour une récidive d’AVC ou présentant soit un syndrome démentiel, soit un score de Rankin ≥3 avant leur AVC, ont été exclus. Le devenir fonctionnel a été apprécié par le score NIHSS, l’index de Barthel et la mesure de l’indépendance fonctionnelle (MIF). Le logiciel Epi-info 6.1 a servi pour l’analyse des données. Quatre-vingt-treize patients hémiplégiques gauches ont été suivis dont 52 (55,91%) sans troubles et 41 (44,09%) avec troubles gnosiques. L’âge moyen était de 60 ans, avec une légère prédominance masculine dans les deux groupes. L’AVC ischémique représentait respectivement 84,62% et 82,93% des lésions vasculaires observées dans les deux groupes.. L’héminégligence était le trouble le plus fréquemment retrouvé, suivi de l’anosognosie. La présence des troubles gnosiques était associée à un mauvais pronostic fonctionnel (p=0,0002) avec un OR ajusté à 3,42 ; IC95% [2,05-6,12] pour l’index de Barthel et 2,49 ; IC95% [1,98-5,39] pour la MIF. L’existence des troubles gnosiques compromet la récupération fonctionnelle des hémiplégiques gauches, soulignant ainsi la nécessité de former et d’insérer des neuropsychologues dans les équipes de rééducation. Mots clés : Hémiplégie gauche, Troubles gnosiques, Récupération, Brazzaville ABSTRACT The aim of our study was to evaluate, in the absence of a neuropsychological rehabilitation, the impact of gnostic disorders on the functional outcome of patients after left hemiplegic stroke. This is a longitudinal study in two functional rehabilitation centers in Brazzaville, from 1st December 2011 to 1st October 2012. The study was to follow for 6 months, two categories of people with left hemiplegia after a first stroke, one side those without the gnostic disorders other with gnostic disorders associated. All patients admitted for recurrent stroke, dementia or a Rankin score ≥ 3 prior to their stroke were excluded. The functional outcome was assessed by the Barthel index and the fonctional independence measure (FIM). Epi-Info 6.1 is used for data analysis. Eighty-three patients with left hemiplegia were followed which 52 (55.91%) without gnostic disorders and 41 (44.09%) with gnostic disorders. The mean age was around 60 years, with a slight predominance of men in both groups. Ischemic stroke accounted for respectively 84.62% and 82.93% in patients without and those with gnostic disorders. The hemineglect disorder was the most often found, followed anosognosia. The presence of gnostic disorders was associated with a poor outcome (p=0.0002) with an adjusted OR 3.42, 95% CI [2.05 to 6.12] for the Barthel index and 2.49, 95 % [1.98 to 5.39] for the FIM. The existence of gnostic disorders impairs functional outcome of left hemiplegic, this shows the need for training and the integration of neuropsychology in rehabilitation teams. Keywords: Left hemiplegia, gnostic Disorders, outcome, Brazzaville INTRODUCTION L’accident vasculaire cérébral demeure jusqu’ici un problème majeur de santé publique. Il représente la première cause du handicap non traumatique de l’adulte. L’hémiplégie résultante est fréquemment associée à d’autres signes en fonction de la latéralité du patient et de l’hémisphère cérébral lésé. Des déficiences gnosiques sont régulièrement observées dans les atteintes hémisphériques droites, leur prévalence pouvant aller de 20 à 60% selon le type de manifestations (2). Ces troubles intègrent le syndrome de l’hémisphère mineur chez le droitier. L’un des volets majeurs dans la prise en charge de l’AVC est la rééducation avec implication de la médecine physique et de réadaptation (MPR) dans une filière de prise en charge bien organisée (12). La rééducation vise la récupération ou la compensation des fonctions perturbées afin de restaurer une autonomie fonctionnelle. Son impact dépend de la qualité des structures existantes et du contexte socio-économique et culturel de chaque pays (6) ; l’effet combiné de l’intensité et la précocité de la rééducation est significativement associé à une bonne récupération (3,10). La présence d’un des éléments du syndrome de l’hémisphère mineur peut compromettre la récupération motrice dans le temps au cours du processus de rééducation (8). En Afrique subsaharienne, peu de services de rééducation fonctionnelle disposent de neuropsychologues ou d’ergothérapeutes ; ce qui explique en partie, l’absence de travaux sur la relation entre les troubles gnosiques du syndrome de l’hémisphère mineur et le devenir fonctionnel des patients en cours de rééducation. Le but de notre étude est d’évaluer l’influence de ces troubles gnosiques dans la rééducation de l’hémiplégique vasculaire gauche, dans un contexte de sous-équipement. PATIENTS ET METHODES Il s’agit d’une étude longitudinale réalisée dans les services de rééducation du CHU de Brazzaville et du centre de santé intégré de Jane Viale à Brazzaville, durant la période du 1er décembre 2011 au 1er Octobre 2012. L’étude a consisté à suivre deux catégories de populations d’hémiplégiques gauches, d’un côté ceux sans troubles gnosiques (STG), de l’autre ceux avec troubles gnosiques associés (ATG). La cohorte a été dynamique avec recrutement consécutif des patients répondant aux critères d’inclusion. Nous avons inclus tous les patients hémiplégiques gauches présentant un premier AVC datant de moins d’un mois, et ayant donné leur consentement pour participer à l’étude. Tous les patients admis pour une récidive d’AVC ou présentant soit un syndrome démentiel, soit un score de Rankin ≥3 avant l’AVC ont été exclus. La recherche des troubles gnosiques du syndrome de l’hémisphère mineur a été réalisée par un neurologue lors de l’examen neurologique systématique de chaque patient. Le devenir fonctionnel a été apprécié par le score NIHSS, la mesure d’indépendance fonctionnelle (MIF) avec les valeurs seuils rapportées usuellement (bon si supérieur à 100, moyen entre 75 et 100, mauvais si inférieur à 75) et l’index de Barthel (IB) avec trois paliers de score : bon si supérieur à 60, moyen entre 60 et 20, mauvais si inférieur à 20. La méthode principale de rééducation a été la rééducation neuro-orthopédique. Des séries d’exercices musculaires adaptées ont été effectuées pour le membre supérieur et pour le membre inférieur. La bicyclette ergothérapique a été utilisée pour le renforcement quadricipital. Chaque patient a bénéficié en moyenne de 3 séances de rééducation par semaine de durée allant de 35 à 40 min. Les patients n’ont pas bénéficié d’ergothérapie telle que requis, ni de rééducation neuropsychologique par manque de spécialiste. Ils ont été évalués en tout début du processus de rééducation, à trois mois et à six mois. Les variables de l’étude ont été l’âge, le sexe, le type de l’AVC, le délai entre la survenue de la maladie et le début de la rééducation. Aucune échelle n’a été utilisée, mais la recherche des troubles gnosiques a été réalisée selon les définitions opérationnelles suivantes : l’héminégligence définie par un défaut de prise en charge des informations issues d’un côté de l’espace (visuospatiale) ou d’un hémicorps (motrice), l’anosognosie définie par la non reconnaissance du trouble, l’hémi-asomatognosie définie par la non reconnaissance de l’hémicorps. Le syndrome de l’hémisphère mineur complet a été retenu devant l’association de l’héminégligence, l’anosognosie, l’agnosie visuelle et des troubles praxiques (5); la mesure de l’indépendance fonctionnelle et l’index de Barthel. Les données ont été analysées à l’aide d’un logiciel épi-info 6.1. Les variables qualitatives ont été présentées sous forme de fréquences absolues et de fréquences relatives exprimées en pourcentage, les variables quantitatives ont été exprimées en moyenne ± écart type. Concernant les fréquences absolues ou effectives nous avons calculé le khi2, et chaque fois qu’il a été en dessous du seuil de significativité, nous avons calculé le khi2 de Yates. Le seuil de significativité a été de 5 % (p< 0,05) et ensuite réalisé les tests de régression logistique qui produit l'OR assortie de son intervalle de confiance à 95%. RESULTATS Durant notre étude, nous avons inclus au début 103 patients. Nous avons enregistré 2 décès soit 1,9% avant l’examen de suivi au troisième mois. Trois patients sont sortis de l’étude pour avoir choisi un relai traditionnel exclusif soit 2,9%. Cinq ont été perdus de vue réalisant un pourcentage de 4,8%. C’est ainsi que notre travail a concerné 93 sujets dont 52 n’avaient aucun trouble gnosique soit 55,91% et 41 en avaient 44,09%. L’âge moyen des patients sans troubles gnosiques était de 61,23 ± 11,39 ans, extrêmes (37 ans et 86 ans). Cette population était composée de 30 hommes (57,69%) et 22 femmes (42,31%). Chez les patients présentant des troubles gnosiques, l’âge moyen a été de 60, 35± 11,04 ans, extrêmes (39 ans et 82 ans). Cette population était composée de 24 hommes (58,54%) et 17 femmes (41,46%). L’AVC était ischémique dans 84,62% des cas et hémorragique dans 15,38% chez les patients sans troubles gnosiques contre 82,93% d’ischémies et 17,07% d’hémorragies chez les patients présentant des troubles gnosiques avec une différence non significative (p=0,89). Concernant le délai d’admission, 38,46% de patients indemnes de troubles gnosiques ont été admis en rééducation dans les délais inférieurs à deux semaines contre 34,15% de patients avec troubles gnosiques (p=0 ,93), et le reste était admis entre la deuxième et la quatrième semaine. La figure 1 représente les principaux troubles gnosiques retrouvés, avec une nette prédominance de l’héminégligence visuo-spatiale. Sur le plan séquellaire, 65,85% des patients présentant des troubles gnosiques avaient gardé des séquelles motrices importantes contre 48,08% dans le groupe des patients sans troubles gnosiques. Cette différente a été statistiquement significative avec un p=0,0002. Le devenir fonctionnel selon l’index de Barthel et la mesure de l’indépendance motrice montre que dans les deux cas, la proportion des patients présentant un mauvais score s’améliore considérablement à 6mois dans le groupe des patients sans troubles gnosiques par rapport à ceux avec troubles gnosiques (Figure 2 et 3), et que l’existence des troubles gnosiques étaient significativement associée à une mauvaise récupération, même après ajustement des deux groupes selon l’âge, la sévérité initiale et le sexe avec respectivement des OR=3,42 ; IC95% [2,05-6,12] et OR=2,49 ; IC95% [1,98-5,39] pour l’IB et le MIF. DISCUSSION Notre travail nous a permis d’évaluer en l’absence d’une rééducation neuropsychologique, l’influence des troubles gnosiques retrouvé dans le syndrome de l’hémisphère mineur sur la récupération motrice. L’évaluation post rééducationnelle peut avoir connu quelque biais car certains patients ont eu, en plus de la rééducation hospitalière, recours à des techniques de massage traditionnel dont les bénéfices sont ignorés. En plus la fréquence des séances de trois fois par semaine est faible pour une récupération optimale dans les deux groupes de notre étude. Ceci étant dû aux effectifs insuffisants du personnel dans nos services de rééducation. Les états anxio-dépressifs qui n’ont pas été pris en compte pour ce travail ont pu également influencer parallèlement la rééducation. Enfin notre étude a porté sur un faible effectif, rendant difficile les possibilités d’inférence statistique, cependant notre effectif corrobore les données africaines qui ont rapporté des séries allant de 30 à 176 patients (4,7,11). Les hémiplégiques gauches sans troubles gnosiques et ceux avec troubles gnosiques ont représenté respectivement 55,91% et 44,09% sur les 93 hémiplégiques gauches enregistrés au total. L’étude de Katz en Israël (11) incluait 19 (47,5%) hémiplégiques avec troubles gnosiques et 21 hémiplégiques sans troubles gnosiques, portant exclusivement sur l’hémi négligence. Dans les deux populations d’hémiplégiques gauches avec ou sans troubles gnosiques nous avons noté une légère prédominance masculine, sans différence significative entre les deux populations concernant le sexe. L’âge moyen des deux groupes était autour de 60 ans, sans différence significative. Zinn et al (15) ont rapporté que les hémiplégiques avec troubles gnosiques étaient significativement plus âgés que ceux sans troubles gnosiques (p=0,02), ce qui contraste avec nos résultats. Concernant le devenir fonctionnel, l’intérêt des échelles choisies, notamment l’index de Barthel et la MIF, réside dans le fait qu’elles intègrent plusieurs modalités, et évaluent la dépendance d’un sujet polydéficient, et qu’il s’agit par ailleurs d’échelles couramment utilisées en soins de suites et réadaptation (9,13). La fréquence des patients qui avaient conservé des séquelles motrices était plus importante chez les patients avec troubles gnosiques avec une différence significativement positive. Cette différence de récupération motrice ne s’explique pas par la sévérité du déficit sensori-moteur initial, comparable dans les deux groupes, mais plutôt et très fort probablement par la présence des troubles gnosiques en particulier l’héminégligence et l’anosognosie considérés comme facteurs pronostiques péjoratifs, de même que par l’absence de rééducation spécifique sur ces troubles. Rohling et al (14) ont rapporté l’efficacité de la rééducation neuropsychologique sur l’héminégligence et le devenir fonctionnel des patients. La valeur absolue de la différence de MIF moyenne entre les deux populations a été plus importante à 3mois qu’à 6 mois ; Cela s’explique très certainement par le fait que pour certains patients même en l’absence d’une rééducation neuropsychologique la déficience cognitive a spontanément régressé au bout de six mois. Par rapport à la MIF, les patients qui ont présenté une association de troubles gnosiques ont eu un moins bon devenir fonctionnel que ceux qui n’ont présenté qu’un seul trouble (p=0,028). Katz et al (11) en étudiant le devenir fonctionnel de 19 héminégligents et 21 non héminégligents trouvaient que les héminégligents avaient un moins bon devenir fonctionnel évalué par la MIF (71 versus 105) avec (P<0,001). CONCLUSION Les troubles gnosiques, plus particulièrement l’anosognosie et le syndrome de l’héminégligence sont fréquemment rencontrés à l’issue des accidents cérébro- vasculaires droits. La recherche de ces troubles devrait être systématique pour tout praticien face à un patient victime d’un AVC hémisphérique droit. Les résultats obtenus dans ce travail attestent bien que ces troubles constituent un frein pour la récupération fonctionnelle et l’acquisition de l’autonomie et doivent être considérés comme des facteurs pronostic péjoratif surtout en l’absence d’une rééducation neuropsychologique. D’où l’intérêt et le besoin d’intégrer dans les équipes de rééducation des compétences en rééducation neuropsychologique. Conflit d’intérêt : Aucun

ABSTRACT Background Objective Design Setting Participants Intervention Main Outcome Measures Results INTRODUCTION Stroke is becoming a serious problem in public health in developing countries, Uganda inclusive, accounting for 85% of global deaths (2, 5, 7, 8, 13, 26, 27, 28, 29). Stroke severity, its associated complications, and lack of stroke units contribute to the high mortality rate found to be as high as 62% at one year (9, 14, 20, 21, 22, 30, 31). Despite this, there is very limited data on stroke mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, and to the best of our knowledge there are no published data on stroke mortality in Uganda. In this study, we reported the 30 day stroke mortality and associated clinical and laboratory presentations among adult patients admitted with stroke at Mulago hospital in Uganda. METHODS Setting: Mulago Hospital is Uganda’s national referral hospital and Makerere University College of Health Sciences’ teaching hospital. It is located in Kampala and has an estimated bed capacity of 1,500. It has an accident and emergency unit, intensive care unit, clinical laboratory, radiology department with a CT scan and highly trained radiologists, neurology, neurosurgery and physiotherapy units. Study period: During a six months period from 1st July 2010 to 30th January 2011, 167 patients who presented to Mulago hospital’s accident and emergency unit with neurologic deficits suggestive of acute stroke (29) were screened. Computerised tomography scan of the brain was done to confirm stroke by radiologists with experience in this field. Classification of stroke subtypes was done using the Trial of ORG 10172 and medical disability guidelines for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke respectively (1, 17). Patients who had a normal brain CT scan, had a repeat done on day 7 and were excluded in case it was still normal. Participants with confirmed stroke were approached for enrolment into the study. Those that consented were recruited consecutively. An interviewer based questionnaire was administered by the principal investigator and trained research assistants. Selected social demographic characteristics, medical history relevant to stroke and a comprehensive clinical examination was done. Blood samples for essential laboratory investigations (complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fasting lipid profile and blood sugar, HIV serology and rapid plasma reagin) were obtained. These patients were reviewed every two days from the day of admission while on the ward until discharge. Upon admission, the patients were managed on the accident and emergency unit, and general neurology unit by a neurologist, internal medicine physicians, nurses and auxiliary staffs. They received supportive treatment which included ensuring a patent airway, good oxygen saturation, haemodynamic stability, nutrition, hydration, temperature and glycaemic control, prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pressure sores. Specific treatment included use of antihypertensive drugs (labetalol and hydralazine) when blood pressure exceeded 180/105mmHg and 160/100mmHg for ischemic and haemorrhagic stroke respectively. Antiplatelet drugs including aspirin and clopidogrel for ischemic stroke and statins were administered. Rehabilitation included physiotherapy, occupational, speech and language therapy. Those that required mechanical ventilation were admitted to the intensive care unit. None of the patients with ischemic stroke benefitted from recombinant tissue plasminogen activator because they presented on average 2 days post ictal. On discharge, they were then scheduled for a neurology outpatient clinic visit that coincided with the 30th day from the date of stroke onset. Participants that did not turn up for the scheduled visit were then contacted by telephone (contacts of three immediate relatives) to ascertain whether they were still alive or dead. Participants who died within 30 days of stroke onset were recorded. RESULTS One hundred and sixty seven patients who presented to Mulago hospital’s accident and emergency unit with neurologic deficits suggestive of acute stroke (29) were screened. One hundred and fifty patients, 18 years and above, were confirmed to have stroke on brain CT scan. Seventeen patients declined to consent for participation in the study and 133 patients were enrolled consecutively into the study. Five participants were lost to follow up and therefore data from 128 participants were analysed. At the end of the follow up period of 30 days from stroke onset, 56 (43.8%) participants had died while 72 (56.2%) were still alive. Stroke mortality was not stratified at 24 hours and seven days from stroke onset as this preliminary study only established stroke mortality at 30 days among adult stroke patients admitted at Mulago hospital. The mean age of the participants was 62.3+15.7 years with a median of 64.5 and 58% were female. Fifty six percent of the participants had never had formal education, 38% were Catholic and 66% were married. Twenty one (15.8%) were taking alcohol while only 3 (2.3%) were current smokers. Social demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Majority of the participants 105 (79%) had ischemic stroke and 28 (21%) had hemorrhagic stroke. All study participants presented with focal neurological deficits, with majority 97 (76%) presenting with only motor deficits. Impaired level of consciousness was present in 78 (61%) patients. More than 50% of the participants had high blood pressure at admission with diastolic and systolic hypertension found among 106(83%) and 68 (53%) respectively. Eighty four (66%) were aware of their hypertension. The clinical characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 2. Most patients 103(80.47%) had haemoglobin levels less than 11.5g/dl followed by hyperglycaemia of more than 7.0 mmol/l in 48 (38%) and leucocytosis in 42 (33%) patients. The laboratory presentations of the study participants are presented in Table 3. Clinical and laboratory parameters that were significantly associated with mortality at bivariate analysis with P- value set at < 0.05 were entered into the multivariate linear logistic regression model. Factors that were significantly associated with 30 day stroke mortality were; age 51-60 years with OR 0.18 (95% CI; 0.04- 0.82) p value 0.044 and Glasgow coma scale < 9 OR 0.13 (95%CI; 0.05-0.25) p value <0.001. Temperature, though not statistically significant at multivariate analysis, it was associated with increased mortality at bivariate analysis OR 2.81 (95%CI; 1.2-6.60) P<0.005. On the other hand, though mortality was higher among patients with hemorrhagic stroke (54%) compared to ischemic stroke (41%), there was no statistically significant difference at bivariate analysis OR 1.71 (95% CI 0.68-4.27). Factors significantly associated with 30 day stroke mortality are presented in Table 4. DISCUSSION Stroke has been demonstrated in this study as a challenge among patients admitted to Mulago hospital. The majority of patients in this study were female 74 (58%). They were also relatively young with mean age of 62.3years similar to other studies in sub-Saharan Africa (21) unlike in the West where the mean age is above 75years (30). The 30-day mortality among stroke patients was 43.8% which is similar to other hospital based stroke case fatality studies in Africa: 54% in Gambia, 33.6% in Nigeria and 49.6% in Maputo Mozambique (6, 10, 20, 21, 22, 25). However in developed countries where patients present early following stroke and care takes place in specialized stroke units, the 30-day stroke mortality is much lower. A study done in Toronto, Canada showed 30 day mortality among stroke patients of 20% (30). Majority of the patients presented with history of loss of consciousness 78 (61 %), Glasgow coma scale less than 9, 38(30 %) and diastolic hypertension 106 (83%) which is comparable with other studies done in resource limited countries (3). A Glasgow coma scale score of less than 9 was associated with increased mortality which is also comparable with other studies done on stroke mortality (23, 30). Regarding stroke subtypes, majority of the patients had ischemic stroke (79%), mortality was higher among those with hemorrhagic stroke, however there was no statistically significant difference in mortality between hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. This is in contrast to other studies, which demonstrated a higher mortality among patients with hemorrhagic stroke (20, 23). In this study, probably we needed a bigger sample size to conclusively come up with a more realistic association. In this study, patients who were between the ages of 51 and 60 years (6th decade) had a higher 30 day stroke mortality rate compared to those who were below 51 and above 60 years. However, those above 70 years of age had the highest 30 day mortality rate which is similar to other studies that showed mortality worsens with advancing age (30). Prevalence of HIV among stroke patients was 12%, which is higher compared to 5.8% in an earlier study done in Mulago among stroke patients in 2007 (19). In the general population the average HIV seroprevalence in Uganda is 7.3% as reported by Ministry of Health, Uganda (24). At Mulago hospital, HIV seroprevalence on the medical wards currently stands at 50 % (16). The HIV seroprevalence among our study participants was much lower than reported from studies done in Muhimbili, Tanzania and Blantyre, Malawi 20.9% and 48% respectively (15, 18). In these two studies, the average mean age of the patients was 47years, which is lower than the mean age in our study which was 63.3 years. CONCLUSION Thirty day mortality among adult stroke patients admitted at Mulago hospital was 43.8%. Delay in hospital presentation and lack of organised inpatient stroke care (stroke units) is likely responsible for this high mortality. Poor prognostic factors for 30 day stroke mortality in our study population were GCS of <9 and age 51-60 years. Future studies should be directed towards increasing stroke prevention and public recognition of stroke to enhance early presentation to hospital as well as setting up organised inpatient stroke care facilities to decrease morbidity and mortality from stroke. Table 1: Social demographic characteristics of the study participants

Table 2: Clinical presentation of the study participants

Table 3: Laboratory presentation of study participants

Table 4: Clinical and laboratory findings significantly associated with 30 day stroke mortality at multivariate analysis

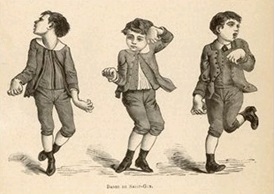

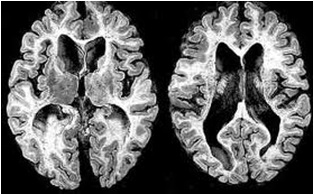

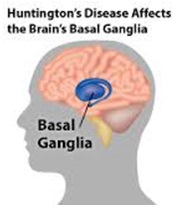

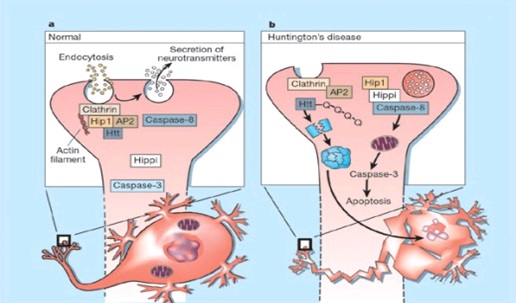

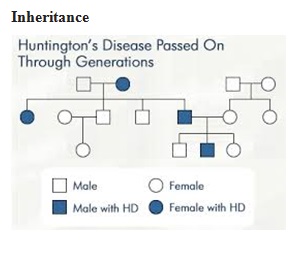

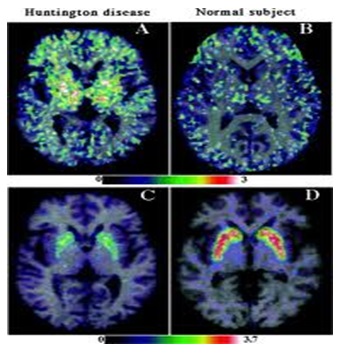

Legend: ABSTRACT Huntington’s disease is an inherited intricate brain illness. It is a neurodegenerative, insidious disorder; the onset of the disease is very late to diagnose. It is caused by an expanded CAG repeat in the Huntingtin gene, which encodes an abnormally long polyglutamine repeat in the Huntingtin protein. Huntington’s disease has served as a model for the study of other more common neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Symptomatic treatment of Huntington’s disease involves use of Dopamine antagonists, presynaptic dopamine depleters, Antidepressants, Tranquillizers,Anxiolytic Benzodiazepines, Anticonvulsants and Antibiotics. Several medications including baclofen,idebenone and vitamin E, Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) have been studied in clinical trials with limited samples. In the present article, we have concentrated on clinical features, diagnosis, symptomatic approaches, symptomatic treatment and other therapies involved in the management of Huntington’s disease. Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Polyglutamine, Huntingtin, Symptomatic treatment INTRODUCTION Huntington’s disease (HD) is a neurodegenerativegenetic disorder that affects muscle coordination and leads to cognitive decline and psychiatric problems. It typically becomes noticeable in mid-adult life. [1] HD is the most common genetic cause of abnormal involuntary writhing movements called chorea, which is why the disease used to be called Huntington’s chorea. [4]For many decades its name remained unchanged, until the nineteen-eighties when, fully aware of the extensive non-motor symptoms and signs, the name was changed to Huntington’s disease (HD). [2] In 1983, a linkage on chromosome 4 was established and in 1993 the gene for HD was found. For the first time, actual pre-manifest diagnoses could be made and as more diseases involving trinucleotide repeats of CAG were found, HD served as a model for many studies in medicine. CAG (cytosine (C), adenine (A), and guanine (G)), is a trinucleotide, the building stone of DNA. CAG is the codon for the amino acid glutamic. Finding the gene opened new research lines, new models and for the first time a real rationale on the way to treat this devastating disease. Many symptomatic treatments are now available, but there is a need for better, modifying drugs. [3] HD is named after George Huntington, the physician who described it as hereditary chorea in 1872. [3, 4]  Figure 1 EPIDEMIOLOGY HD affects males and females in relatively equal numbers. The disorder occurs in various geographic and ethnic populations worldwide. The frequency of HD appears to vary among different populations, ranging from an estimated 4 to 10 individuals in 10,000.[6]Huntington’s disease shows a stable prevalence in most populations of white people of about 5-7 affected individuals per 100000. [7] Exceptions can be seen in areas where the population can be traced back to a few founders, such as Tasmania and the area around Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela. In Japan, prevalence of the disorder is 0.5 per 100 000, about 10% of that recorded elsewhere, and the rate is much lower in most of Asia. African populations show a similarly reduced prevalence, although in areas where much intermarriage with white people takes place the frequency is higher. [6, 7] Currently, the higher incidence of Huntington’s disease in white populations compared with African or Asian people relates to the higher frequency of Huntingtin alleles with 28-35 CAG repeats in white individuals. [8] SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS Huntington’s disease is a widely variable disorder, even within the same family. The early symptoms of Huntington’s disease generally include slight, uncontrollable muscular movements, Chorea, stumbling and clumsiness, lack of concentration, lapses of short-term memory, depression, and changes of mood, sometimes including aggressive or antisocial behavior. [2, 3]The rate of progression of Huntington’s disease varies, but generally, it develops over 15-25 years. [5] Later in the illness, people may experience different symptoms, which include involuntary movements, Difficulty in speech and swallowing, Weight loss as well as emotional changes, resulting in: Stubbornness, Frustration, Mood swings, Depression. Chorea (derived from the Greek word meaning to dance) is the most common movement disorder seen in HD. [4] Chorea is a characteristic feature of HD and, until recently; the disorder commonly was called Huntington chorea. [9] Chorea, as defined by the World Federation of Neurology, is a state of excessive, spontaneous movements, irregularly timed, randomly distributed, and abrupt which is evidently illustrated in figure 2. Severity of chorea may vary from restlessness with mild intermittent exaggeration of gesture and expression, fidgeting movements of the hands, and unstable dance like gait to a continuous flow of disabling violent movements. Initially, mild chorea may pass for fidgetiness. [2] Severe chorea may appear as uncontrollable flailing of the extremities (i.e., ballism), which interferes with function.  Figure 2 Cognitive decline is characteristic of HD, but the rate of progression among individual patients can vary considerably. Dementia and the psychiatric features of HD are perhaps the earliest and most important indicators of functional impairment. [4]The dementia syndrome associated with HD includes early onset behavioral changes, such as irritability, untidiness, and loss of interest. PATHOLOGENOIUS The selective neuronal dysfunction and subsequent loss of neurons in the striatum, cerebral cortex, and other parts of the brain can explain the clinical picture seen in cases of HD. Several mechanisms of neuronal cell death have been proposed for HD, including excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, impaired energy metabolism, and apoptosis. [10] I. Exciting toxicity Excitotoxicity refers to the neurotoxin effect of excitatory amino acids in the presence of excessive activation of postsynaptic receptors. Intrastriatal injections of kainic acid, an agonist of a subtype of glutamate receptor, produce lesions similar to those seen in HD. [11] Intrastriatal injections of quinolinic acid, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor agonist, selectively affect medium-sized GABA-ergic spiny projection neurons, sparing the striatal interneuron’s and closely mimicking the neuropathology seen in HD. NMDA receptors are depleted in the striata of patients with HD, suggesting a role of NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity, but no correlation exists between the distribution of neuronal loss and the density of such receptors.[5, 11] The theory that reduced uptake of glutamate by glial cells may play a role in the pathogenesis of HD also has been proposed. II. Oxidative stress Oxidative stress is caused by the presence of free radicals (i.e., highly reactive oxygen derivatives) in large amounts.[12] This may occur as a consequence of mitochondrial malfunction or excitotoxicity and can trigger apoptosis. Striatal damage induced by quinolinic acid can be ameliorated by the administration of spin-trap agents, which reduce oxidative stress, providing indirect evidence for the involvement of free radicals in excitotoxic cell death. [13] III. Impaired energy metabolism Impaired energy metabolism reduces the threshold for glutamate toxicity and can lead to activation of excitotoxic mechanisms as well as increased production of reactive oxygen species.[8] Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies have shown elevated lactate levels in the basal ganglia and occipital cortex of patients with HD.[12] Patients with HD have an elevated lactate-pyruvate ratio in the cerebrospinal fluid. A reduction in the activity of the respiratory chain complex II and III (and less in complex IV) of mitochondria of caudate neurons in patients with HD has been reported. [14]  Figure 3 The genetic basis of HD is the expansion of a cysteine-adenosine-guanine (CAG) repeat encoding a polyglutamine tract in the N -terminus of the protein product called Huntingtin. The function of Huntington is not known. Normally, it is located in the cytoplasm. [19, 20] The association of Huntingtin with the cytoplasmic surface of a variety of organelles, including transport vesicles, synaptic vesicles, microtubules, and mitochondria, raises the possibility of the occurrence of normal cellular interactions that might be relevant to neuro-degeneration. N-terminal fragments of mutant Huntingtin accumulate and form inclusions in the cell nucleus in the brains of patients with HD, as well as in various animal and cell models of HD. [18] The presence of neuronal intra nuclear inclusions (NIIs) initially led to the view that they are toxic and, hence, pathogenic. More recent data from striatal neuronal cultures transfected with mutant Huntingtin and transgenic mice carrying the spinocerebellar at axia-1 (SCA-1) gene (another CAG repeat disorder) suggest that NIIs may not be necessary or sufficient to cause neuronal cell death, but translocation into the nucleus is sufficient to cause neuronal cell death.Caspase inhibition in clonal striatal cells showed no correlation between the reduction of aggregates in the cells and increased survival. [19] PATHOLOGY The most striking pathology in HD occurs within the neostriatum, in which gross atrophy of the caudate nucleus and putamen is accompanied by selective neuronal loss and astrogliosis. Marked neuronal loss also is seen in deep layers of the cerebral cortex. [16] Other regions, including the globuspallidus, thalamus, sub thalamic nucleus, substantianigra, and cerebellum, show varying degrees of atrophy depending on the pathologic grade. [17] The extent of gross striatal pathology, neuronal loss, and gliosis provides a basis for grading the severity of HD pathology. No gross striatal atrophy is observed in grades 0 and 1. Grade 0 cases have no detectable histologic neuropathology in the presence of a typical clinical picture and positive family history suggesting HD. [16, 17] Grade 1 case have neuropathological changes that can be detected microscopically but without gross atrophy. In grade 2, striatal atrophy is present, but the caudate nucleus remains convex. In grade 3, striatal atrophy is more severe, and the caudate nucleus is flat. In grade 4, striatal atrophy is most severe, and the medial surface of the caudate nucleus is concave. [17, 18]  Figure 4  Figure 5 HUNTINGTIN The Huntington’s disease is still not fully understood. What is known about Huntington’s disease is that it occurs due to mutations in a single gene coding for a protein called Huntington. [20]Huntingtin is expressed in all human and mammalian cells, with the highest concentrations in the brain and testes; moderate amounts are present in the liver, heart, and lungs. [21] Recognizable autologous of protein is present in many species, including zebra fish, drosophila, and slime moulds. The role of the wild-type protein is, yet, poorly understood, as is the underlying pathogenesis of Huntington’s disease.[21, 22]One mechanism by which an autosomal-dominant disorder such as Huntington’s disease could cause illnesses by haploin sufficiency, in which the genetic defect leads to inadequate production of a protein need for vital cell function.This idea seems unlikely because terminal deletion or physical disruption of the HDgene in man does not cause Huntington’ disease. [15, 16] Furthermore, one copy of the HDgene does not cause a disease phenotype in mice. Whereas homozygous absence of the HDgene is associated with embryonic lethality in animals, people homozygous for the HDgene have typical development.Findings suggest that the mutant HDgene confers toxic gain of function. [3, 4, 5] A persuasive line of evidence for this idea comes from nine other known human genetic disorders with expanded (and expressed) polyglutaminerepeats: spinocerebellar ataxia types, Dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy, and spinobulbar muscular atrophy. For none of these disorders is there evidence to suggest an important role for haplo insufficiency. [24] In spinobulbar muscular atrophy, complete deletion of the androgen receptor is not associated with neuromuscular disease. All nine diseases show neuronal inclusions containing aggregates of polyglutamines and all have a pattern of selective neuro-degeneration.One of the most striking features of these disorders is the robust inverse correlation between age of onset and number of polyglutamine repeats. [10] Results suggest that the length of the Polyglutamine repeat indicates disease severity irrespective of the gene affected, with the longest repeat lengths associated with the most disabling early-onset (juvenile) forms of these disorders. Although difficult to confirm, some data also suggest that the rate of progression might be faster with longer CAG repeats, particularly for individuals with juvenile-onset disease. [19]The most convincing evidence for a gain of function in Huntington’s disease is the structural biology of polyglutamine strands. [10, 11] This process needs a specific concentration of protein and a minimum of 37 consecutive glutamine residues, follows a period of variable abeyance and proceeds faster with higher numbers of glutamine repeats. These findings might account for both delayed onset of disease and the close correlation with polyglutamine length. The rate of aggregation increases with the number of glutamine residues, which accords with evidence showing that length of expansion is associated with early age of onset. [2, 3, 10] CLINICAL FINDINGS Individuals with Huntington’s disease can become symptomatic at any time between the ages of 1 and 80 years; before then, they are healthy and have no detectable clinical abnormalities. [1, 5]This healthy period merges imperceptibly with a pre-diagnostic phase, when patients show subtle changes of personality, cognition, and motor control. Both the healthy and pre-diagnostic stages are sometimes called presymptomatic, but in fact, the pre-diagnostic phase is associated with findings, even though patients can be unaware of them. Diagnosis takes place when findings become sufficiently developed and specific. In the pre-diagnostic phase, individuals might become irritable or disinherited and unreliable at work; multitasking becomes difficult and forgetfulness in addition, anxiety mounts.Family members note restlessness or fidgeting, sometimes keeping their partners awake at night. [8, 31] Eventually, this stage merges with the diagnostic phase, during which time affected individuals show distinct chorea, in coordination, motor impersistence, and slowed saccadic eye movements. Cognitive dysfunction in Huntington’s disease, often spares long-term memory but impairs executive functions, such as organizing, planning, checking, or adapting alternatives, and delays the acquisition of new motor skills. These features worsen over time; speech deteriorates faster than comprehension. [9]Unlike cognition, psychiatric and behavioral symptoms arise with some frequency but do not show stepwise progression with disease severity. Depression is typical and suicide is estimated to be about five to ten times that of the general population (about 5-10%). [4] Manic and psychotic symptoms can develop. Suicidal ideation is a frequent finding in patients with Huntington’s disease. In a cross-sectional study, about 9% of asymptomatic at-risk individuals contemplated suicide at least occasionally, perhaps a result of being raised by an affected parent and awareness of the disease. In the pre-diagnostic phase, the proportion rose to 22%, but in patients who had been recently diagnosed, suicidal ideation was lower. The frequency increased again in later stages of the illness. [6, 7] The correlation of suicidal ideation with suicide has not been studied in people with Huntington’s disease, but suicide attempts are not uncommon. In one study, researchers estimated that more than 25% of patients attempt suicide at some point in their illness. Individuals without children might be at amplified risk, and for these people access to suicidal means (i.e., drugs or weapons) should be restricted. The presence of affective symptoms, specific suicidal plans, or actions that increase isolation (e.g., divorce, giving away pets) warrants similar precautions.Although useful for diagnosis, chorea is a poor marker of disease severity. Patients with early onset Huntington’s disease might not develop chorea, or it might arise only transiently during their illness. [1, 5] JUVENILE HD If the first symptoms and signs start before the age of 20 years, the disease is called Juvenile Huntington’s disease (JHD). Behaviors disturbances and learning difficulties at school are often the first signs. Motor behavior is often hypokinetic and bradykinetic with dystonic components. Chorea is seldom seen in the first decade and only appears in the second decade. Epileptic fits are frequently seen. The CAG repeat length is over 55 in most cases. In 75% of the juveniles the father is the affected parent. [21, 19] A complete and accurate family history is invaluable in evaluating a child with symptoms suggestive of Huntington disease, and can make the process of diagnosis much more straightforward. [22] However, there are situations in which parents may not even be aware that HD is in the family; in other cases, an adopted child may be involved. A number of tests may be used in conjunction with the presence or absence of a family history, and clinical presentation, to help clarify the diagnosis. Inheritance  Figure 6 It is elucidated with example in the figure 6 that the dark colored animation is being affected and semi darks are at risk and finally the light colored are not affected. DIAGNOSIS Diagnosis of HD is not easy andrequires an extensive care while diagnosing. The discovery of the HD gene in 1993 resulted in a direct genetic test to make or confirm a diagnosis of HD in an individual who is exhibiting HD-like symptoms. Using a blood sample, the genetic test analyzes DNA for the HD mutation by counting the number of repeats in the HD gene region. [11, 15]Pre-symptomatic testing is used for people who have a family history of HD but have no symptoms themselves. The blood test confirms the presence or absence of the HD mutation. It is encouraged that patients have either a blood sample from a family member who has HD or the results of his/her genetic test for confirming the diagnosis. [31] If either parent had HD, the person’s chance would be 50-50.Prenatal testing is one of a range of options, which may be of interest to couples who are at risk of passing the disease-causing version of the HD gene to a child. And also, chorionic Villi Sampling is done to identify the presence of HD. In the past, no laboratory test could positively identify people carrying the HD gene or those fated to develop HD before the onset of symptoms. [25]  Figure 7 Upon presence of contrast agent, the microglial cells in HD and normal brain are well assessed. Imaging technologies allow investigators to view changes in the volume and structures of the brain and to pinpoint when these changes occur in HD. Scientists know that in brains affected by HD, the basal ganglia, cortex, and ventricles all show atrophy or other alterations. [20] TREATMENT There is no cure for Huntington’s disease, and there is no known way to stop the disease from getting worse. The goal of treatment is to slow down the symptoms and help the person function for as long and as comfortable as possible. [26, 30]

Table 1 : Symptomatictreatmentregime [26-28, 30] Table 1 is an overview of treatment options for HD. As there is no complete cure, a symptomatic treatment regime is followed. In August 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Tetrabenazine to treat chorea, making it the first drug approved for use in the United States to treat the disease. [28] In the year 2012, a clinical study is initiated on Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) for treating HD. Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) are artificial restriction enzymesgenerated by fusing a zinc finger DNA-binding domain to a DNA-cleavage domain. [33] Expanded CAG/CTG repeat tracts are the genetic basis for more than a dozen inherited neurological disorders including Huntington’s disease, myotonic dystrophy, and several spinocerebellar ataxias. [20] It has been demonstrated in human cells that ZFNs can direct double-strand breaks (DSBs) to CAG repeats and shrink the repeat from long pathological lengths to short, less toxic lengths. CONCLUSION Several medications including baclofen, idebenone and vitamin E have been studied in clinical trials with limited samples. More research work and clinical trials should be done to search effective drug molecules that would provide a more rational approach in the treatment of Huntington’s disease. The more research should be aimed to develop therapeutic agents that alter the course of neurodegenerative disease like preventing neuronal death or stimulating neuronal recovery. As there is no specific cure for HD, the goal of current research is to develop treatments that can prevent, retard or reverse neuronal cell death. More specific treatments for Huntington’s disease should become feasible.

Programme et résumé du 21ème congrès de la PAANS ( téléchargement ) Program and abstract of the 21st congress of the PAANS ( download ) Articles récents

Commentaires récents

Archives

CatégoriesMéta |

© 2002-2018 African Journal of Neurological Sciences.

All rights reserved. Terms of use.

Tous droits réservés. Termes d'Utilisation.

ISSN: 1992-2647