|

|||||||||||

|

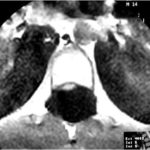

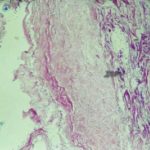

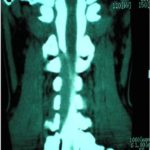

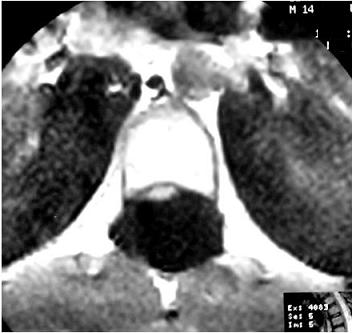

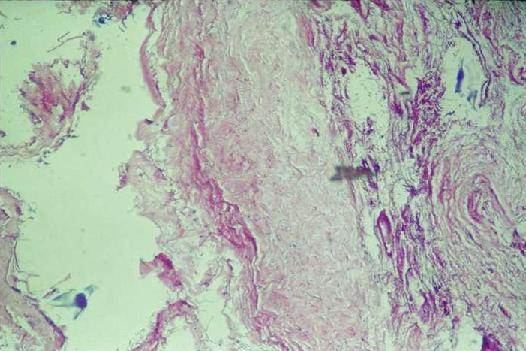

RESUME Le kyste arachnoïdien extra-dural spinal est une affection rare. Sa pathogénie reste méconnue. Mots-clés : kyste arachnoïdien, kyste extradural ABSTRACT Spinal extradural arachnoid cysts are uncommon. The pathogenesis of this entity is still unclear. Here, we report a 12-year-old girl with unremarkable past medical history was referred to our institution of neurosurgery, Avicenna military hospital, Marrakech, with progressive spastic paraparesis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a posterior extradural cystic lesion extending from the T6 to T8 levels in the thoracic region. The cyst was completely removed by posterior approach. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of arachnoid cyst. Neurological symptoms progressively resolved after surgical decompression. Keys-words: arachnoid cyst, extradural cyst, MRI INTRODUCTION Le kyste arachnoïdien extra-dural spinal, décrit comme un kyste « méningé » ou poche OBSERVATION Une jeune fille de12 ans, sans antécédents pathologiques notables, était hospitalisée pour une lourdeur des deux membres inférieurs évoluant depuis un an. Depuis un mois, elle ne pouvait marcher sans aide et présentait une incontinence urinaire. Cette symptomatologie évoluait dans un contexte d’apyrexie et de conservation de l’état général. L’examen neurologique, à l’admission, a révélé une paraparésie spastique avec une irritation pyramidale aux deux membres inférieurs, des troubles sensitifs superficiels et profonds de niveau ombilical. Les radiographies simples du rachis dorsal et lombaire de face et profil étaient normales. DISCUSSION Le kyste arachnoïdien extradural spinal est une affection bénigne relativement rare (3,9). Sa topographie est essentiellement thoracique, s’étendant sur plusieurs vertèbres avec un pic de plus grande fréquence autour de la huitième vertèbre dorsale (3). La localisation cervicale ou lombo-sacrée est très rare (6,7). Les localisations dorsales sont particulièrement fréquentes à la seconde décade de la vie compte tenu de l’étroitesse canalaire à ce niveau et les localisations lombosacrées s’observent plus tardivement entre 30 et 50 ans (15,17). Par rapport au fourreau dural, le kyste arachnoïdien extradural spinal est habituellement de siège postérieur ou postérolatéral, cependant, une extension à travers un trou de conjugaison peut quelquefois être notée (17). L’étiopathogénie reste hypothétique et plusieurs théories ont été présentées (3,9). Les kystes spinaux extra duraux ont probablement une origine congénitale. Cette dernière est le résultat d’une hernie de l’arachnoïde à travers une aplasie congénitale de la dure mère (3,4,5,14). Cependant, il peut y avoir une absence de communication libre entre le kyste et l’espace sous-arachnoïdien (3). Cette communication siège souvent sur la ligne médiane ou à proximité d’une racine (17). Le defect de la dure mère est due à une anomalie structurale, d’origine congénitale, conséquence d’une défaillance de l’étanchéité des fibres collagènes. Cette défaillance conduit à un allongement et une ectasie de la dure mère (8). L’accroissement du kyste dépendrait pour Cloward (5) de 3 facteurs : la pression hydrostatique du L.C.R. la pression osmotique intra kystique et la sécrétion par la paroi kystique. Le kyste arachnoïdien extra-dural spinal est le plus souvent asymptomatique. Cependant la compression nerveuse est rarement décrite (9,14). Devenant compressif, il se révèle volontiers par une parésie progressive de type spastique d’un ou des deux membres inférieurs associée à des paresthésies ou à des troubles sphinctériens et génitaux. Ailleurs il s’agit de douleurs radiculaires suivies plus ou moins rapidement d’un déficit moteur (3). Nabors et al. (13) le classent en trois types : type 1 = kyste arachnoïdien extra-dural sans compression nerveuse, type2 = kyste arachnoïdien extra-dural avec compression nerveuse (comme dans le cas de notre patiente) ; type 3 = kyste arachnoïdien intra-dural. La radiologie standard du rachis peut montrer des signes liés directement à la présence du kyste. Les signes directs comprennent l’élargissement du canal rachidien et des foramens ainsi que d’une augmentation de la distance interpédiculaire, d’un amincissement pédiculaire ou d’une image de scalopping et l’ombre du kyste qui sont totalement absents dans notre cas (3 ,16). Des anomalies osseuses dysraphiques peuvent être décelées en association avec le kyste arachnoïdien (11). L’IRM reste l’examen complémentaire idéal pour ce type de pathologie vu sa grande sensibilité et spécificité pour les lésions contenant du LCS. Elle a l’avantage de montrer de façon non invasive le siège exact, la taille, l’étendue et le degré de compression nerveuse. De plus, il a l’avantage de guider le choix de la voie d’abord chirurgicale (7,12). Le kyste se présente comme une masse allongée mesurant de 5 à 10 cm en moyenne, siégeant derrière le cordon médullaire et de même signal que le LCS aussi bien sur les séquences T1 et T2. (3). L’injection intraveineuse de gadolinium est utile pour écarter les autres lésions qui peuvent prêter confusion tel un kyste synovial ou une tumeur kystique et tout particulièrement un hémangioblastome spinal (2). La ciné-IRM est une nouvelle technique qui permet non seulement de visualiser les mouvements du liquide dans le kyste et autour du cordon médullaire mais aussi de préciser le siège exact de la communication afin de limiter l’étendue de la laminectomie (14). CONCLUSION Le kyste arachnoïdien extradural spinal est une affection bénigne, mais il peut, par son potentiel évolutif, engendrer des troubles neurologiques importants et permanents en l’absence d’une prise en charge précoce.  Figure 1A  Figure 1B Figure.1 : IRM médullaire: a) en coupe axialeT1, b) en coupe sagittale T1. Elle montre une formation kystique intracanalaire extradural, en hyposignal s’étendant de D6 à D8.  Figure 2 Figure. 2 : IRM médullaire, en coupe sagittale T2 : Processus kystique de même signal que le liquide céphalo-rachidien.  Figure 3 Figure. 3: Coupe histologique montrant la paroi kystique tapissée par place de cellules arachnoïdiennes.

C’est avec douleur ,tristesse et peine qu nous vous annoncons le deces apres une longue maladie du Professeur FATOU SENE DIOUF ,notre plus jeune agrégée du Service de NEUROLOGIE de DAKAR, le Jeudi 13 Aout 2009;elle a ete inhumée le lendemain dans la ville sainte de TOUBA.. Que le Seigneur Tout Puissant l’accueille dans son Paradis PROFESSEUR M MANSOUR NDIAYE «L’homme qui ne craint pas la vérité n’a rien à craindre du mensonge.» «The man who does not fear the truth does not have anything to fear lie.» «L’instinct dicte le devoir et l’intelligence fournit des prétextes pour l’éluder.» «The instinct dictates the duty and the intelligence provides pretexts to elude it.» Values Our priorities are to serve the following: First: Beneficiaries: Children, teens, adults, families and communities Second: Advocates: ThinkFirst Network – Chapter Directors, Schools, VIPs, Physicians and Health Care Professionals Third: Sponsors: Hospitals, Medical Associations, Government Organizations, and Corporations UN CAS D’HEMATOME EXTRADURAL CERVICAL NON TRAUMATIQUERESUME L’hématome extradural cervical spontané est une pathologie rare mais une sévère cause de compression médullaire. Il requiert un diagnostic et une prise en charge urgents. Nous en rapportons un cas chez une patiente de 20 ans sans antécédent pathologique, révélé par un syndrome de compression médullaire cervical sévère (grade A de Frankel). Une décompression neurochirurgicale est intervenue avec un délai de 48H avec comme corollaire de lourdes séquelles. Les auteurs insistent sur l’intérêt d’un diagnostic et d’une prise en charge précoces pour en minimiser les séquelles neurologiques. Mots clés : Hématome extradural spontané – Rachis cervical. ABSTRACT Spontaneous cervical extradural hematoma is a rare pathology but a severe spinal cord compression cause.We report a case revealed by a severe spinal cord compression (Frankel rank A) in a 20 old female patient without past medical history. A neurosurgical decompression has been performed 48 hours later which result of important after-effects. Key words: Spontaneous extradural hematoma, cervical spine INTRODUCTION L’hématome extradural cervical spontanée ou hématome épidural est une collection hémorragique touchant l’espace épidural [3]. Il s’agit d’une pathologie rare se présentant typiquement comme une compression médullaire cervicale aiguë. Elle nécessite un diagnostic et une prise en charge urgents, gages d’un pronostic fonctionnel et parfois vital meilleur. OBSERVATION Madame KA 20 ans sans antécédent particulier a été admise dans notre service au motif d’une quadriplégie installée 48 heures plutôt. L’interrogatoire notait un début brutal marqué par des cervicalgies intenses rapidement associées à un déficit moteur hémicorporel droit se bilatéralisant au bout de quelques minutes aboutissant à une quadriplégie complète. L’interrogatoire ne retrouvait ni contexte traumatique, ni prise médicamenteuse antérieure. Une décompression chirurgicale a été réalisée le même jour et il s’agissait d’un volumineux hématome extradural qui a été complètement évacué. La recherche par la suite d’une tare hémorragipare s’est avérée infructueuse. DISCUSSION L’hématome extradural cervical spontané est une pathologie rare [3,8,9] mais une sévère cause de compression médullaire [2]. L’incidence de l’hématome épidural spontané en général, est estimé à 0.1 pour 100.000 habitants et moins d’un pour cent (1%) de l’ensemble des lésions touchant l’espace épidural [1]. Il s’agit du premier cas que nous rapportons en 16 années d’activité. Divers antécédents telles qu’une coagulopathie, une malformation vasculaire, une maladie de Paget ou la prise d’anticoagulant exposent à la survenue de cette pathologie [9]. La majorité des hématomes a une localisation postérieure mais l’hématome en rapport avec une hernie discale a une localisation ventrale par rapport au fourreau dural [8]. L’IRM demeure actuellement l’examen de choix pour le diagnostic neuroradiologique de l’hématome extradural cervical [5,8]. Il apparaît en hyposignal par rapport à la moelle à T1 et en hypersignal à T2. En dehors des aspects classiques, une lésion inflammatoire ou tumorale peut être mimée par un hématome surtout en cas de rehaussement inhabituel [2]. Cette confusion est très fréquente avec comme corollaire un retard diagnostic et thérapeutique. Dans nos pays où l’IRM est bien souvent absente, l’examen clinique prend une place de choix dans les investigations diagnostiques et couplé au myéloscanner cervical, peut conduire au diagnostic. L’existance au myeloscanner d’une lésion hyperdense biconvexe au contact de la dure-mère doit faire evoquer le diagnostic. D’un point de vue thérapeutique, la décompression neurochirurgicale en urgence est recommandée par la plupart des auteurs [3,6,8,9] comme étant le meilleur traitement. CONCLUSION L’hématome extradural cervical est une pathologie rare mais une sévère cause de compression médullaire. Cette pathologie pose des problèmes de diagnostic differentiel avec les myéloradiculites d’installation rapidement progressif ce qui peut en retarder le diagnostic. Elle impose un diagnostic et surtout une décompression neurochirurgicale urgents chez des patients qui bien souvent ont un contact initial avec les services des urgences médicales. Cette décompression devra intervenir dans les 8 premières heures afin d’améliorer le pronostic déjà sévère de ces patients. Ce délai très court dans nos conditions de travail doit être le but à atteindre. Tableau 1 : Classification de FRANKEL

Figure 1  Figure 2

Articles récents

Commentaires récents

Archives

CatégoriesMéta |

© 2002-2018 African Journal of Neurological Sciences.

All rights reserved. Terms of use.

Tous droits réservés. Termes d'Utilisation.

ISSN: 1992-2647