|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

INTRODUCTION Neurology has remained a relatively rare specialty in Nigeria leaving several patients under/misdiagnosed and therefore mismanaged. With less than 60 neurologists practicing in different states of the country, the current specialist to patient ratio is approximately 1:30000006. The sub-optimal management of neurological disorders in Nigeria is also due to the prohibitive cost of investigations and medications in addition to the inadequacy of rehabilitative services in the country2. This is especially so when the cost of care is borne out of pocket. Lagoon Hospitals Hygeia is the largest private hospital franchise in Nigeria with more than 30 years of quality healthcare service delivery in all specialties in medical practice. The hospital records the most successful implementation of insurance medicine and managed health care nationwide. It serves more than 40 Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs); delivers standard health care to public civil servants under the coverage of the National Health Insurance Scheme; and has a robust base of patients who access services within its facilities privately. The services available for the management of neurological disorders include the immediate access to brain imaging (CT/MRI); round the clock laboratory services; an efficient intensive care service for life threatening presentations; and a structured neuro-rehabilitation team comprising physical, nutritional; speech and occupational therapists with a common goal to reduce the morbidity and mortality from these disorders to a bearable minimum and improve the functional outcome of patients managed. The aim of this study was to describe the pattern of neurological disorders seen in the hospitals’ Adult Outpatient Neurology Clinics and add to the available data that guide the allocation of human and material resources towards the optimum management of neurological disorders and the advancement of neurological services offered by the hospital. METHOD The electronic records of all outpatient cases seen by the author over a three year period (July 2014 and Dec 2017) were retrieved and reviewed. All general medical cases were immediately excluded. Neurological disorders were grouped into 18 broad diagnoses using the ICD 10 nomenclature: Cerebral Palsy, unspecified; Sequelae of other infectious and parasitic diseases (CNS Infections); Sequelae of Inflammatory Disease of the Central Nervous System (CNS Inflammation); Toxic Effect, Organophosphate and Carbamate Insecticides (CNS Poisoning); Dementia, unspecified; Dizziness and Giddiness; Epilepsy, unspecified; Headache; Malignant Neoplasm, brain unspecified (CNS Neoplasms); Extrapyramidal and Movement Disorder, unspecified (Movement Disorders); Myasthenia gravis (Neuromuscular Diseases); Peripheral Neuropathy, unspecified; Somatoform disorder, unspecified (Psychiatry); Sleep Disorders, unspecified; Nerve Root and Plexus Compressions in Spondylosis; Stroke not specified as hemorrhage or infarction; Syncope; and Trauma19. Data was inputted on the Microsoft Excel 2010 spreadsheet and the distribution of the diagnoses was analyzed using frequency tables and percentages. RESULTS A total of 3724 outpatient visits were recorded out of which 1468 (39.41%) were strictly neurological. Headache, spondylosis, stroke, epilepsy, peripheral neuropathies and movement disorders were the most frequent diagnoses constituting 28.47%; 18.32%; 14.58%; 9.60%; 8.65%; and 8.17% respectively of the visits to the hospital. Among the patients with headache, tension-type headache was the most frequent diagnosis (41.39%) while migraine headaches constituted 27.99%. The remainder was accounted for by the Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias (especially Cluster Headache) and other unspecified headache syndromes. Ischemic stroke constituted 84.11% of recorded stroke cases while intracerebral hemorrhage made up 4.67%. All were confirmed by neuroimaging studies. About 9.82% of the stroke cases were not specified. Among the degenerative diseases of the spine, cervical spondylosis was the most frequently diagnosed reason for consultations (63.2%). Peripheral neuropathies were mainly extracranial (73.22%) while cranial mono-neuropathies (facial, trigeminal and hypoglossal nerve lesions) constituted 12.6%; 11.82%; and 2.36% respectively. Forty two percent (42%) of the patients with epilepsy were noted to have focal seizures while the remainder was unspecified.

Table 1: Neurology Outpatient Cases seen in Lagoon Hospitals over a 3 Year Period

Table 2: Headache Visits in Lagoon Hospitals over a Three (3) Year Period

Table 3: Outpatient Stroke Cases seen in Lagoon Hospitals over Three (3) Years

Table 4: Outpatient Cases of Spondylosis in Lagoon Hospitals over a Three (3) Year Period

Table 5: Outpatient Cases of Peripheral Neuropathy in Lagoon Hospitals over Three (3) Year Period

Table 6: Outpatient Cases of Epilepsy seen over a Three (3) Year Period

Table 7: Movement Disorders seen in Lagoon Hospitals over a Three (3) Year Period

DISCUSSION Clinical practice data from private healthcare institutions in Nigeria is quite sparse and this is more apparent in rare specialties like neurology10. This study recognizes headache as the most common reason for outpatient adult neurology consultations in Lagos accounting for more than 28% of all the visits (Table 1). A similar finding has been presented by Tegueu et al from a private urban clinic in Yaounde, Cameroun where headache accounted for 31.9% of all the visits in the adult neurology clinic16. In contrast, stroke and epilepsy dominate the neurology clinics in tertiary healthcare institutions in Nigeria which already have a large amount of data identifying stroke as the most commonly admitted neurological disorder5,11, 15. The accurate definition of the type of headache a patient experiences is absolutely relevant to its management (Table 2). While most primary headaches may have characteristic clinical features, the author recommends a low threshold for brain imaging considering the limitations of clinical evaluation. This is certainly practicable when healthcare is insured as obtained for most patients in Lagoon Hospitals. Of equal importance is the use of a “headache diary” which is a very simple clinical tool that helps patients to better define the characteristics of their symptoms with emphasis on the identification of triggers. Stroke constituted about 14% of the visits to the clinic making it the 3rd most common disorder (Table 1). In agreement with other local and international studies, cerebral infarction was the most common type (Table 3), accounting for about eighty four per cent of all cases1,4,7,14. Stroke prevention strategies have gained popularity in our environment largely as a result of the increasing popularity of the benefits of cardiovascular fitness. While acute stroke intervention strategies are more established for ischemic stroke, they are currently not employed in the routine management of patients because very few are eligible at the time of presentation and the cost implications are enormous17,20. More emphasis on stroke prevention and the early recognition of stroke are being encouraged by neurologists all over the world to reduce the burden of this illness. Epilepsy accounted for 9% of the clinic visits in this study and was the 4th most reason for clinic visits (Tables 1 and 6). Worldwide, it is a common neurological disorder with a higher incidence and prevalence rates in rural areas, underdeveloped countries and in the pediatric age group3. The current study was however carried out in the adult neurology clinic of a private hospital that caters mainly for the middle and high income earners and situated in an urban, cosmopolitan city in Nigeria. It is not surprising therefore that it was more common in the government owned tertiary institutions12,13,18. Although the data presented suggests that localization related epilepsies are more common, this classification was based on the clinical diagnosis and not on the patients’ EEG results. EEG is routinely offered to newly diagnosed epileptics in our hospital and another study is currently underway to accurately classify these disorders based on clinical and EEG findings. Movement disorders were the 6th most frequent cases seen in our clinic, accounting for about 8% of the total number of visits with Parkinsonism, Tremors and Dystonias topping the charts (Tables 1 and 7). This agrees with the results of Okubadejo et al as seen in the Premier Movement Disorders Clinic in Nigeria8. While the popularity of this sub-specialty is growing at an international level, more awareness is needed among general practitioners regarding the recognition of the basic features and phenomenology of movement disorders to encourage early initial management and referral. More collaborative efforts such as exist between the College of Medicine, University of Lagos and the International Parkinson’s and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) through conferences and courses organized within the country hope to improve this trend7. The Asynchronous Consultations in Movement Disorders (ACMD) is another initiative of the MDS, which is a telemedicine based avenue for cross referrals among doctors all over the world. Strict video recording protocols are employed for consenting patients to ensure standard diagnosis and feedbacks. These and other initiatives will certainly improve the lot of affected patient. Spondylosis (and other degenerative diseases of the spine) constituted 18% of the total visits and were the second most common disorders treated in the clinic (Table 1). Along with stroke, they constituted a sizeable proportion of the outpatient visits, similar to the findings in other studies12,16. The dominance of both disorders in this preliminary study reflects the need for and collaboration between neurologists and other providers of neuro-rehabilitative therapy, especially physical therapy, which is implicit in their management. It also calls upon investors in healthcare to re-examine the marketability of neuro-rehabilitative services in Nigeria. LIMITATIONS At the time of this study, the available diagnoses obtained from the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) of our hospital were based on the 2014 Version of the ICD 10. However, more recent versions of this internationally accepted method of disease classification offer a wider and more specific array of diagnoses. Also, a significant number of the diagnoses inputted on the EMR were classified as “unspecified”. This suggests that the actual distribution (and frequency) of the specific disease entities may have been under- or over- reported. CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS In the typical outpatient adult neurology practice, stroke, headaches, epilepsies, movement disorders and degenerative diseases of the spine are five commonly seen disorders and therefore the most likely to offer the largest returns for investors in neurology and neuro-rehabilitative medicine. The call for the continuous expansion of the health insurance coverage among Nigerians must continue to be emphasized to guarantee optimum delivery of quality healthcare in our country. ACKNOWLEDGMENT: The Management and Privileging Committee of Lagoon Hospitals Hygeia; Mr. Adekunle Omidiora & Mr. Olusola Omotoso for providing access the relevant Electronic Medical Records; and Prof Yomi Ogun for his kind review of this article and insightful suggestions. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: None LA NEUROMYELITE OPTIQUE DE DEVIC (NMO) EN CÔTE D’IVOIRE: A PROPOS D’UN DEUXIEME CAS CONFIRMEINTRODUCTION La Neuromyélite optique (NMO) est une maladie inflammatoire démyélinisante du système nerveux central qui cible sélectivement le nerf optique et la moelle épinière, même si elle peut également cibler certaines zones du cerveau (11). Longtemps considérée comme une variante de la sclérose en plaques, elle est aujourd’hui reconnue comme une pathologie bien distincte dont le traitement et le pronostic diffèrent (3). La découverte d’un biomarqueur spécifique, un auto-anticorps ciblant l’aquaporine-4, présent chez la majorité des patients a permis l’élargissement du spectre de la NMO (NMOSD) à des formes isolées de myélite ou de névrite optique rétrobulbaire, ainsi qu’à des formes avec atteintes encéphaliques ou du tronc cérébral. L’élargissement du spectre de la maladie a fait proposer le terme d’« aquaporinopathie auto-immune ». L’évolution clinique de NMO est dominée par des attaques aiguës (11). L’objectif de ce travail est de présenter le second cas documenté de NMO en Côte d’Ivoire à travers l’observation d’une jeune femme ayant présenté des signes d’atteinte médullaire et optique. OBSERVATION Nous rapportons le cas d’une jeune femme âgée de 31 ans hospitalisée au service de médecine physique et de réadaptation pour la prise en charge rééducative d’une paraplégie d’installation progressive associée à des troubles vésico-sphinctériens et des escarres. La patiente n’avait aucun antécédent pathologique particulier. Au niveau gynéco-obstétrique elle avait fait deux épisodes d’interruption volontaire de grossesse (IVG). L’histoire de la maladie révèle un début des signes qui remonterait à 15 mois avant son hospitalisation, marqué par la survenue de paresthésie puis d’un déficit moteur des membres inférieurs. Deux autres poussées de déficit neurologique ont été noté dans l’évolution, d’abord une aggravation du déficit moteur des membres inférieurs puis une cécité monoculaire gauche. L’examen neurologique à son admission au service de médecine physique et de réadaptation a objectivé une mydriase aréflexique gauche, une paraplégie spastique, une escarre sacrée stade III et une incontinence vésicale et anale. En cours d’hospitalisation soit à J 27, la patiente a présenté une baisse brutale et rapidement progressive de l’acuité visuelle de l’œil droit. L’examen neurologique a alors noté une mydriase réactive droite. L’examen ophtalmologique a noté une atrophie optique temporale gauche et un fond d’œil normal à droite. L’examen cytobactériologique et chimique du LCS après la ponction lombaire a été sans anomalie. La recherche d’Ac anti NMO dans le LCS a été faiblement positive. La sérologie HIV a été négative. L’imagerie médullaire notamment l’IRM de la moelle-thoracique et cervicale (Figure 1 et Figure 2) a retrouvé un hypo signal en Echo de spin T1, un hyper signal en Echo de spin T2 médullaire en en faveur d’une myélite étendue. Aucune imagerie encéphalique n’a pu être réalisé. Le diagnostic de Neuromyélite avec anticorps anti-aquaporine 4 positif a été retenu selon les critères diagnostic de la NMO (Figure 3). L’attitude thérapeutique ayant permis l’amélioration de l’acuité visuelle a consisté en une corticothérapie à forte dose débuté à J1 à raison de 1g/jour pendant 03 jours puis 60mg /jr pendant 01 mois. DISCUSSION La neuromyélite optique est une affection inflammatoire rare du système nerveux central (1). Elle a longtemps été considérée comme une forme particulière de SEP. Cependant de nouveaux critères diagnostics ont permis d’en faire une affection à part entière. Le diagnostic repose sur les critères de Wingerchuck et al (10) qui regroupent : Neuropathie optique rétrobulbaire, une Myélite transverse aigue et au moins deux des trois critères suivants : IRM encéphalique normale (ou non évocatrice de SEP) ; une IRM médullaire avec 1 lésion étendue sur au moins 3 segments vertébraux et les NMO-IgG/AQP4Ab séropositifs. Notre observation présente le deuxième cas confirmé de NMO en Côte d’Ivoire depuis 2015 (12). Elle révèle un double intérêt. Premièrement l’intérêt de la suspicion clinique devant l’évolution par poussée aigue d’une atteinte médullaire associée à une atteinte optique. Devant ces atteintes, le diagnostic est fortement évoqué chez une jeune femme avec antécédent d’interruption volontaire de grossesse (IVG). La NMO est plus fréquente chez les femmes et l’âge médian est de 35 à 37 ans (5). L’IVG est un facteur avec une association significative de survenue de la NMO (4). Le diagnostic positif est approché par l’IRM médullaire retrouvant une myélite longitudinale étendue supérieure à trois métamères ou segment vertébraux (10). L’IRM encéphalique lorsqu’elle est réalisée est anormale dans 60% des cas avec 6% de cas de lésion évocatrice d’une NMO (7). Dans notre cas, l’IRM encéphalique n’a pu être réalisé du fait surtout du coût financier. La positivité des Ac Anti NMO a été l’argument majeur du diagnostic. Les difficultés diagnostiques ont été décrites dans d’autres observations en Afrique noire aussi bien par Yapo-Ehounoud et al (12) et Maiga Y et al (6). Ces difficultés diagnostiques, peuvent-être dues non seulement à la méconnaissance de cette affection mais aussi à la difficulté de la réalisation du bilan paraclinique qui est à la charge du patient. Secondairement l’intérêt de l’utilisation de la corticothérapie d’emblée à la phase aigüe de la poussée inflammatoire qui permet une rémission de la symptomatologie. Dans notre cas l’instauration de la corticothérapie à forte dose dès les premiers signes de la poussée aigue a permis la régression totale de la symptomatologie. Le consensus actuel repose en première intention sur l’utilisation d’échange plasmatique et ou corticothérapie à forte dose lors des poussées aigue suivi d’un traitement de fond reposant sur l’immunosuppression général ou sélective (l’azathioprine, le mycophénolate mofétil, le rituximab et la mitoxantrone) (9, 2). En urgence, nous avons pu instaurer dans notre cas la corticothérapie cependant, aucun traitement de fond n’a pu être instaurer du fait non seulement du manque de moyens financiers mais aussi du fait des croyances culturelles de la patiente et des accompagnants. L’évolution de la NMO est dominée par des attaques aigues (11), comme présenté dans notre cas et celui de Yapo-Ehounoud (12). Aussi, la myélopathie dans la maladie de Devic est le plus souvent associé avec une mauvaise régression (8). CONCLUSION La NMO est une affection rare. Cependant la suspicion clinique devant l’association clinique de la NORB et la myélite transverse aigue doit faire évoquer le diagnostic et faire rechercher les critères diagnostic. La corticothérapie reste le traitement de choix à la phase aigüe de la poussée dans notre contexte de travail.

ICONOGRAPHIES  Figure 1 : IRM thoracique en coupe sagittale séquence T2 montrant un hyper signal étendu intramédullaire

Figure 2 : IRM du rachis cervical en coupe sagittale séquence T2 montrant un hyper signal intramédullaire HEALTH FACILITY-BASED PREVALENCE AND POTENTIAL RISK FACTORS OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN MALI INTRODUCTION On average 1 in 68 children in the U.S. are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), but significant variations in prevalence depending on geographic area, sex, race/ethnicity, and level of intellectual ability exist (5). Autistic individuals have impaired reciprocal social interaction and communication, restricted repetitive and stereotyped behaviors (17). Girls experience fewer restricted and repetitive behaviors and externalizing behavioral problems (34). ASD are clinically classified by the severity of the disorder, language level, and the presence of learning disability/mental retardation (20). The onset or the diagnosis can be early around three years old or late in adolescence or adulthood (25). Comorbidities such as epilepsy, intellectual disability, and tuberous sclerosis are frequent (25, 32). A well-coordinated worldwide effort to identify risk factors for ASD and to meet the needs of persons with ASD and their families is needed from the global scientific community. Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) can significantly contribute in a unique way to a better understanding of the etiology, the genetic and environmental risk factors the influence of cultural backgrounds on ASD diagnosis and the preferences of treatment options based on parental perceptions (12, 16). However, ASD is currently understudied in Africa where its prevalence is unknown. More genetic epidemiology studies on ASD are needed in Africa in general and West Africa in particular (3). The University of Sciences, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako (USTTB), Mali, has been collaborating with the University of California Los Angeles, UCLA, U.S and the University of Cape Town (UCT), South Africa to establish an ASD genetic research platform and awareness in Mali for West Africa. Ultimately, such collaborative genetic research will lead to a better understanding of the genetics basis of ASD in populations with Black African ancestry in West Africa and elsewhere. In Mali, our aims were (i) to describe the landscape of ASD diagnosis and management (ii) to determine the health facility-based prevalence of ASD (iii) to implement our ASD awareness campaign across the country and (iv) to identify potential ASD risk factors. METHODS To describe the landscape of ASD and the health facility-based prevalence of ASD in Mali, we identified in 2014 all the public and private health facilities and organizations involved in the diagnosis and management of ASD in Bamako. We reviewed the outpatient medical charts of 12,000 children aged 3-14 years old treated at our study sites (the psychiatry department of the University hospital Point G, AMALDEME and three private medical clinics (Kaidara, Solidarite and Algi) from 2004 to 2014. We gathered information from 2,343 medical charts with neuropsychiatric disorders in our study questionnaire. Data were collected mainly by three junior investigators (a neuroscientist, a neurologist and a fourth year psychiatry resident) at our study sites. The following diagnostic criteria (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM–5 for ASD (1), The International League Against Epilepsy, ILAE official report, 2014 for epilepsy (11) and the International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10 for other neuropsychiatric disorders (35)) by psychiatrists in the hospital, a neurologist at the private medical clinics Solidarite and Algi and by a neuro-paediatrician at the private medical clinic Kaidara) were used in our study. We diagnosed autism spectrum disorder (ASD) on the basis of difficulties in two areas – social communication, and restricted, repetitive behaviour or interests according to the DSM-5 criteria. ASD cases were female or male children aged 3-14 years old and controls (epilepsy or other neuropsychiatric disorders) were age and sex matched. We selected two controls (one epileptic and one with another neuropsychiatric disorder) for each ASD case for risk estimation.” The psychiatry department of the teaching hospital Point G was our main study site. A weekly child outpatient visit (including autistic children) has now been running for a decade at the psychiatry department in Point G. Patients and their families benefit from the free psychological support and weekly music therapy (Kotéba national) conducted by the National Institute of Arts of Mali, under supervision of the medical psychologist. In 2010 and 2013, the first two associations of autistic families were created. To determine the health facility-based prevalence of ASD, we also contacted in Bamako every single health facility or organization involved in ASD diagnostic, care, awareness seeking collaboration. To implement our ASD awareness campaigns, we have done various ASD awareness activities in urban and rural Mali. Since 2016, an ASD awareness conference is organized for the international autism day on April 2nd in Bamako. A 1-day seminary for information and education of parents of autistic children, traditional healers and medical doctors is held at the FMOS annually. A survey was conducted to determine the baseline knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of Malians on ASD (AAS open, manuscript in review). To engage the decision-makers, we presented our ASD research program before the Malian House of Representatives in 2017 and the chief of the cabinet of the first Lady of Mali. Private and public media were associated heavily involved in our ASD awareness events from the beginning. In rural Mali, we took advantage of the existing health information system to reach out to the local population. In 2018, we designated the Autism Ambassadors and Animators of Mali whose task was to use their leadership and networking to raise the ASD awareness in the general population and among the decision and policy makers. To identify the potential ASD risk factors, we calculated the odds ratio using the proportion of presence of a particular potential ASD risk factor in autistic children as compared to age and sex matched controls with either epilepsy or other neuropsychiatric disorders. Our data were analyzed using SPSS20. The significance of the p value was set at <0.05. For the OR calculation, normal variant or absent of abnormality was used as the reference. RESULTS The health facility-based prevalence of ASD was 4.5% (105/2,343) in Bamako (Table 1). The male to female ratio was 1.5/1. A total of 86.7% (91/105) autistic children were from Bamako and 58.1% (61/105) were managed at the psychiatry department of the teaching hospital Point G. Autistic children were unschooled in 88.6% (93/105) of cases. On average, seven (7) autistic had the first medical visit each year (105 autistic children from 2004 to 2014) with the highest rates in 2009 (n=13) and 2012 (n=22) (Table 2). Autistic children were born to first degree consanguineous marriage and abnormal pregnancy four times as frequently as compared to children with epilepsy OR=4.47 [2.00-9.96] p=0.0002 and OR=4.83 [1.02-22.91] p=0.006, respectively (Table 3). Autistic children were born to first degree consanguineous marriage and a multipara woman (>7 births) with a family history of psychiatric disorder on the paternal side two times as frequently as compared to children with epilepsy OR=2.72 [1.35-5.47] p=0.0007, OR=2.38 [1.06–5.33] p=0.05 and OR= 2.97 [1.11-7.91] p=0.04, respectively (Table 4). DISCUSSION Health facility-based prevalence of ASD in Mali In this study, we found 4.5% (105/2,343) autistic children in Mali (Table 1), a good estimation of the magnitude of ASD in Mali. In Nigeria, ASD was found to be among the least frequent infantile neuropsychiatric disorders with an incidence of 2.3% of 2,320 (2, 18). In one way, this is over-estimated due to study participant selection bias in our study sites where clinicians were either a child neurologist, child psychiatrist or a neuro-pediatrician. In another way, it may be underestimated because most parents do not seek care for their autistic children due to either the stigma surrounding autism or prefer traditional to the conventional medicine influenced by either local beliefs and ignorance or the difficult accessibility and unaffordability of available mental health services in Bamako. Consequently, the mean age at the first outpatient visit in our cohort was 7.64± 3.85 years old in Bamako (Table 2) as compared to the mean age at diagnosis of 3 years 10 months in the U.S. and 44.7 (Standard Deviation=21.2) months in Nigeria (18, 29). Rural, near-poor children and those with severe language impairment received a diagnosis 0.4 years later than urban children; 0.9 years later than those with incomes >100% above the poverty level and 1.2 years earlier than other children (29). The presumably delayed diagnosis of ASD in Malian children based on the mean age of first medical visit was a real concern. An earlier ASD screening and diagnosis coupled with early appropriate psychosocial intervention will definitely lead to a better outcome in Malian autistic children. Therefore, the modified checklist for toddlers–Revised/Follow up (M-CHAT-R/F) and the social communication questionnaire (SCQ) were validated into the Malian sociocultural context in Bamako in 2017 (23). Autistic children were unschooled in 88.6% (93/105) (Table 2). Special education and behavior therapy are rare or absent in our resources limited settings (21, 24). Due to the lack of Applied behavioral analysis (ABA) services, atypical antipsychotic risperidone is widely prescribed to autistic children at the psychiatry of Point G (personal communication with the head department) to improve various behavioral problems as suggested in the literature (13). On average, seven autistic had the first medical visit each year (105 autistic children from 2004 to 2014) with the peaks in 2009 (n=13) and 2012 (n=22) (Table 2). The peaks coincided with the year of creation of the two previous associations of parents of autistic children in Bamako. This suggests the importance of the active involvement of autistic parents to the ASD awareness campaigns to promote medical care seeking behaviors. Potential ASD risk factors in Mali From our retrospective study, we found that abnormal pregnancy, consanguinity, family history of psychiatric disorders were potential ASD risk factors in Mali. Children born to mothers from abnormal pregnancy OR: 4.83 [1.02-22.91] p=0.06 and those from consanguineous marriage OR= 4.47 [2.00-9.96] p=0.0002 and those had four times were increased risk of being autistic as compared to their age and sex matched peers born to normal pregnancy by non-consanguineous couples. Exposures to environmental factors (alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, illegal drugs) during pregnancy as possible risk factors for autism have been investigated in numerous epidemiological studies with inconsistent results (19). The rate of consanguinity, a marriage between cousins or relatives, in the cohort of families with neuropsychiatric disorders ranges from 13% to 30% in Mali (7, 28, 30). Consanguineous families, with syndromic and non-syndromic autism will be worth investigating for the discovery of new recessive ASD genes in Mali. When compared with vaginal delivery, either emergency or planned C-section has consistently been associated with an increased risk of ASD (4). The Malian government sponsored C-section to make it free all over the country in 2009 increasing drastically the C-section rate in the country (9). Consequently, Mali had an overall C-section rate in facilities of 31.0% from 2014 to 2016 (6). Despite such high rate, C-section was found in only 5 (4.8%) autistic versus 2 (1.9%) controls OR=2.5 [0.47-13.17] p=0.28 whereas Meguid et al., 2018 reported C-section and neonatal jaundice as the most common risk factors of ASD in Egypt (22). Our main study site was the psychiatry department. We observed that pediatricians are more likely to inquire about C-section in caring for children as compared to psychiatrists. Psychiatrists focus more on the maternal mental health (31). A family history of psychiatric disorder (when at least one person from either the maternal or paternal family had history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (33)) on the paternal side two times OR= 2.97 [1.11-7.91] p=0.04 (Table 3). Family history of mental illness may be more relevant in adolescent onset psychosis and a child is more likely to get a mental illness diagnosis in the presence of family history of psychiatric disorder (26). Lagunju et al., reported 22.6% children (n=54) had a positive family history of autism, and 75.5% had associated neurological comorbidities (18). Besides co-morbidities, overlap between clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorders has been described in the literature (10, 28). Mothers who had seven or more births were as twice as likely to have autistic children as compared to epileptic controls OR=2.38 [1.06–5.33] p=0.05 (Table 4). This could be explained by the advanced maternal age at the conception, but we did not gather information on the birth order of the autistic children in their respective families. Implementation of ASD awareness campaigns in Mali The Association Djiguiya in tandem the Autism Ambassadors and Animators of Mali including the ex-Ministry of higher education geared up the ASD awareness activities this year. Malian health authorities and significant stakeholders are on board to create a center for Autism Research and Training (CART) in Mali. The landscape of ASD in Mali As a result from describing the landscape of ASD in Mali, a multidisciplinary Malian ASD research team was built to generate preliminary data, to consolidate collaboration with foreign institutions such as the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and the University of Cape Town (UCT). A unified national association of parents of autistic children “Association Djguiya” was created in January 2018 to carry out ASD awareness activities and support ASD research in Mali. Due to our cultural representation of ASD in sub-Saharan Africa, most parents still prefer traditional and spiritual healing, partly due to the lack of appropriate treatment, and financial burdens of the conventional medical practice (8, 14, 15, 27). The Kotéba national, a psychotherapy technique designed based on the psychodrama of Jacob Levy Moreno (29) will be a good resource educating the general Malian population on ASD. CONCLUSION This study shows a high health facility prevalence of autism and a significant relationship to first degree relatives and to a paternal history of psychiatric illness. The important public health implications of these findings substantiate the detailed and unique methodology used in this study. This is a new development in ASD screening, diagnostic, care and research in Mali. Instead of “the same size fits all” policy for autistic children, the standard of ASD diagnosis and care has been raised in Mali far behind the systematic prescription of atypical and classic antipsychotic drugs to compensate for the lack of ABA specialists in Mali. The association “Djiguiya” took the ASD awareness campaigns with unexpected progress within year 1 of its creation. Our collaborative autism genetic research is new and unique in Africa and should inspire ASD and mental health researchers in neighboring countries. Our ultimate goal is to embrace the global autism awareness to establish a comprehensive autism research and training program in Mali for West Africa. CONFLICT OF INTEREST “The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.” ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to Professor Kenneth H Fischbeck and Professor Peturs De Vries for their continuous support during this work. FUNDING STATEMENT “Dr. Modibo Sangare, MD, PhD was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from a DELTAS Africa grant (DEL-15-007: Awandare). The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust (107755/Z/15/Z: Awandare) and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust or the UK government.” Dr. Modibo Sangare was also a grantee of the University of Sciences, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of Mali.

Table 1: Health facility-based prevalence of neuropsychiatric disorders in Bamako, Mali

*West syndrome (n=12), myoclonic seizures (n=5), etc… *Hydrocephalia (n=8), brain tumor (n=7), meningoencephalitis (n=7), brain malformation (n=5), head trauma (n=2), microcephalia (n=2), brain atrophy (n=2), hypoplasia (n=1), neurofibromatosis (n=1) §Cerebellar ataxia (n=9), dystonia (n=3), chorea (n=3), essential tremor (n=1)

Table 2: Socio-demographic information of the autistic children and their matched controls

*Neuropsychiatric disorders different from autism and epilepsy **Year of first outpatient visit was the year when the patient was seen for the first time at one of our study sites. The mean age of patients at the first outpatient visit was 7.64 ± 3.85 years.

Table 3: Potential ASD risk factors in autistic versus epileptic children in Mali

Table 4: Potential ASD risk factors in autistic versus neuropsychiatric disorders in Mali

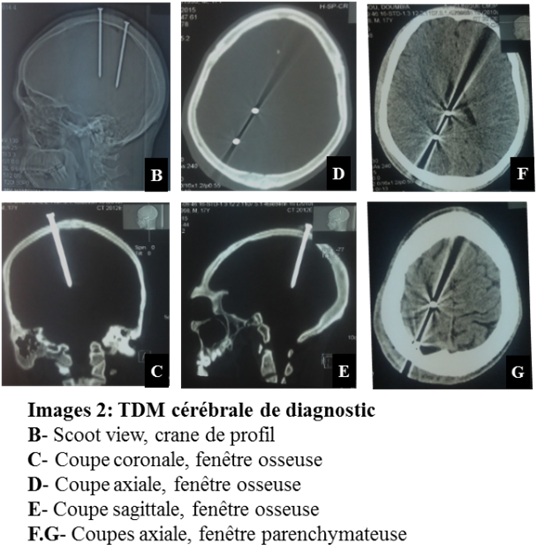

*other neuropsychiatric disorders different from epilepsy TRAUMATISME CRANIEN PENETRANT NON PROJECTILE PAR DES CLOUS: UN CAS INHABITUEL INTRODUCTION Les traumatismes crâniens pénétrants par des clous sont rares et potentiellement fatals s’ils s’accompagnent de plaie vasculaire intracrânienne (10). Ils surviennent à la suite d’accidents de travail ou domestique (16) et d’automutilation (contexte psychiatrique) pour la plupart (18). Ils sont rarement secondaires à une agression physique. La prise en charge reste ambiguë tant sur le plan chirurgical de ces lésions, notamment avec le développement de techniques chirurgicales (16) que sur les explorations radiologiques pré et postopératoire. Ils constituent une cause majeure de décès et d’invalidité en structures neuro-vasculaires (4). L’observation que nous rapportons est particulière par le contexte du traumatisme, le mécanisme de survenu et l’agent vulnérant utilisé. CAS CLINIQUE Notre observation porte sur un jeune homme âgé de 29 ans, sans emploi, qui a été victime d’un traumatisme crânien par agression physique de la part d’une foule lors d’une tentative de vol en novembre 2016. En effet, surpris par le gardien d’une concession lors du vol de bijoux, le patient fut appréhendé par une foule déchainée venue à l’appel au secours du gardien. Après avoir été couvert des coups, le jeune garçon a subi une exécution extrajudiciaire qui a consisté à l’implantation d’une paire de clou dans le crâne (Images 1-A). A son arrivée aux urgences, accompagné par la police, le patient était conscient avec un score de Glasgow à 15. Il décrivait des céphalées associées à des paresthésies à type de fourmillements et une hypoesthésie à la main gauche. L’inspection du crâne avait mis en évidence la présence de deux corps étrangers métalliques implantés en région pariétale droite (Image 1-A). Le reste de l’examen était sans particularité. Le scanner cérébral réalisé en urgence (Image 2) confirmait le passage endocrânien de chacun des deux clous. Il n’y avait pas d’hématome intracérébral. L’angioscanner et l’artériographie n’ont pas été réalisés. L’indication de l’ablation chirurgicale des clous a été posée dans la foulée. En préopératoire, le patient a bénéficié d’une séroprophylaxie antitétanique à base d’anatoxine tétanique 0,5 millilitre en sous cutané et d’une antibioprophylaxie par le ceftriaxone à la dose de 2 grammes par jour. L’intervention sous anesthésie générale avait consisté en la réalisation d’une incision droite prolongeant de part et d’autre l’orifice d’entrée du corps étranger et à tailler une petite rondelle de craniectomie autour du clou (Image 3-H). Après le retrait de celui-ci et le contrôle de l’hémostase, la rondelle osseuse avait été remise à sa place et la peau fermée en deux plans sans drainage. A la mensuration, les clous mesuraientchacun 8 centimètres (cm) de long (Image 3-I). En postopératoire immédiat, outre le traitement antalgique, le patient avait été mis sous prévention antiépileptique à base de valproate de sodium 500 milligrammes (mg), un comprimé toutes les 12 heures pour une durée de deux mois avec la poursuite de l’antibioprophylaxie à raison de 2g toutes les 12 heures pendant 10 jours. Les suites opératoires ont été simples. Le patient a présenté son refus de réaliser le scanner de contrôle et l’angioscanner cérébral devant une amélioration favorable marquée par la régression de troubles sensoriels de la main gauche. Au douzième jour, les points de suture ont été retirés et le patient asymptomatique sans syndrome infectieux est sorti de l’hôpital. Revu en consultation à 3 semaines, il signalait des céphalées minimes calmées par le paracétamol. Durant un suivi de 15 mois, l’évolution clinique était satisfaisante. DISCUSSION Les traumatismes crâniens pénétrant à faible énergie cinétique sont rares et ne représentent que 0,4% de tous les traumatismes crâniens (10,16). Ils surviennent de préférence chez l’adulte jeune de sexe masculin (8,10,23) comme dans notre observation. Les traumatismes crâniens pénétrants non projectiles sont de faible vélocité inférieure à 100 mètres par seconde (3). L’objet pénétrant la boite crâne par des orifices non naturels nécessite une certaine énergie cinétique pour vaincre la protection fournie par l’os. L’épaisseur du crâne et sa distribution convexe minimisent les effets de la frappe, ce qui rend ces traumatismes moins sensibles (10). Leur gravité immédiate est lié eaux lésions vasculaires intracrâniennes que peut causer l’objet pénétrant. Secondairement, les complications infectieuses sont à redouter du fait que le corps étranger est considéré comme étant porteur de bactéries. L’usage des clous comme agent vulnérant n’est pas fréquent. En effet, la plupart des traumatismes crâniens par des clous surviennent dans le contexte d’automutilation chez les personnes psychotiques utilisant de façon préférentielle le pistolet à clous (18). (Tableau I). Les cas de survenue accidentelle se répartissent entre les accidents domestiques concernant surtout les enfants et les accidents de travail dont sont victimes les adultes (16). L’implantation à vif d’une paire de clou de longue taille dans le crâne d’un individu relève d’une cruauté extrême. Ce genre d’agression physique dont a été victime notre patient est exceptionnel. De 2006 à nos jours, nous avons répertorié 22 cas de traumatisme crânien par des clous dont seulement quatre étaient secondaires à une agression physique (6,9,10,24). Tous ces cas concernaient l’adulte de sexe masculin à l’exception d’un seul survenu chez un garçon de 4 ans. Dans la majorité des cas, l’état clinique du patient est très peu compromis (Tableau I). Le tableau clinique est surtout fonction du siège de l’atteinte cérébrale et des dommages vasculaires intracrâniens engendrés. Les troubles sensitifs de la main gauche rencontrés chez notre patient sont liés à une atteinte du cortex somato-sensitif du côté droit par le clou. Un grand nombre de controverses existent par rapport au choix des examens radiologiques à visée diagnostique. Si la majorité des auteurs optent pour la radiographie du crâne associée à la tomodensitométrie (TDM) cérébrale (Tableau I) (6, 9,12, 13, 22,), d’autres ont associé une angiographie cérébrale aux deux examens précédents (3, 8,18). Chen al. (7) avaient préféré la TDM et l’angioscanner cérébral. La rareté du cas, le contexte et l’absence d’un protocole d’exploration dans notre contexte de travail ont fait que la TDM cérébrale a été le seul examen réalisé. En l’absence de l’artériographie non disponible dans notre centre, la réalisation d’un angioscanner cérébral peut contribuer à la recherche de lésions vasculaires liées au passage intracrânien des clous. Ainsi, l’exploration radiologique d’un traumatisme crânien pénétrant par des clous devra nécessairement comporter une TDM avec angioscanner cérébral. En cas de doute d’une lésion vasculaire, une artériographie sera réalisée. La prophylaxie antiépileptique, antitétanique et antibiotique est importante en cas de passage intracérébral de clou du fait de la lésion corticale par un objet métallique potentiellement infesté de germes. Très peu d’auteurs avaient effectué la prophylaxie antiépileptique (3,20) comme ce fut le cas dans notre observation avec le valproate de sodium. Cette pratique n’est pas encore validée par des études scientifiques. Toutefois, il est à noter qu’environ 30% à 50% des patients victimes de traumatisme crânien pénétrant développent des crises à la suite d’une lésion traumatique directe du cortex cérébral avec une cicatrisation subséquente (15). Li et al. recommandent des anticonvulsivants prophylactiques au cours de la première semaine suivant le traumatisme à cause du risque élevé d’épilepsie (16). Cette prophylaxie peut aller jusqu’à 6 mois en l’absence de crise (10). La prévention antitétanique effectuée chez notre patient n’a été retrouvée que dans une seule observation (1). L’ablation chirurgicale du clou est indiquée pour prévenir ou réduire les dommages secondaires et les complications tardives. Pour cela, l’intervention devra être réalisée la plus précocement possible. Il n’existe pas de stratégie standard pour le retrait chirurgical du corps étranger. L’objectif étant d’être le moins traumatique et le moins délétère possible, l’analyse minutieuse des examens radiologiques, la parfaite connaissance de l’anatomie du cerveau pourront aider à l’extraction sans encombre du métal introduit. Certains auteurs ont proposé la réalisation d’examens radiologiques peropératoires afin de détecter de façon précoce un saignement intracrânien secondaire à l’extraction du corps étranger (3,5). Cette attitude demande une logistique et des manœuvres qui ne sont pas particulièrement indispensables. L’acte chirurgical à foyer ouvert permet de s’affranchir de cette attitude. La craniectomie est l’approche chirurgicale optimale pour l’ablation d’un clou intracrânien avec effraction de la dure-mère. Elle permet de contrôler le geste en cas d’hémorragie. Pour les corps étrangers qui n’ont pas traversé la dure-mère, un simple retrait sous anesthésie locale peut être effectué (10). Awori et al (3) trouvent que la présence d’un corps étranger retenu n’est pas considérée comme une indication absolue d’intervention chirurgicale (3). De notre point de vue, la chirurgie d’un corps étranger à type de clou se justifie par le risque potentiel d’infection même si celui-ci est situé en sous cutané. Tous les auteurs sont d’accord sur l’antibioprophylaxie, mais avec des molécules et des protocoles différents. Les antibiotiques à large spectre sont les plus recommandés (8,3,14). Ceux qui traversant la barrière hémato-encéphalique peuvent apporter un meilleur résultat (16). Dans notre observation, le Ceftriaxone a été utilisé pendant 12 jours avec un résultat satisfaisant. Le choix de l’antibiotique et de la durée de l’antibiothérapie est fonction du siège du corps étranger (sous cutané ou intracérébral) et de l’habitude les équipes. La surveillance post-opératoire évalue l’état neurologique du patient avec le score de Glasgow (GCS). Elle recherchera aussi les éléments en faveur de crises d’épilepsie, de fuite du liquide cérébro-spinal (LCS), des troubles endocriniens et infectieux. La fuite du LCS survient dans 0,5% à 3% des cas de traumatisme crânien pénétrant (21). Cette complication n’a pas été observée chez notre patient. Les patients porteurs de traumatisme crânien pénétrant avec un corps étranger non stérile sont à une population à risque de développer des infections, telles que les abcès cérébraux et la méningite. L’administration d’antibiotiques peut réduire les risques de cette complication. Les dysfonctionnements endocriniens peuvent se voir par atteinte hypophysaire par le corps étranger. La prise en charge associera les endocrinologues pour corriger les éventuels troubles métaboliques et endocriniens. Outre la TDM cérébrale de contrôle qui doit être réalisée dans les 72 heures à la recherche de complications sécondaires à type d’hématome de la loge opératoire, il est souhaitable de répéter l’angioscanner et l’artériographie cérébrale 2 à 3 semaines plus tard (11). Ces deux examens rechercheront un faux anévrisme lié à une lésion vasculaire par le corps étranger. Le score de Glasgow (GCS) initial avant la prise en charge est un facteur pronostic important. Un GCS initial inférieur à 15 serait prédictif d’une évolution défavorable (10). Notre patient n’avait pas présenté de trouble de la vigilance. Sa prise en charge a été favorable avec une évolution clinique satisfaisante. CONCLUSION Le traumatisme crânien pénétrant par des clous est rare et se voit surtout dans un contexte d’automutilation chez les patients psychiatriques. Les cas secondaires à une agression sont exceptionnels. Le score de Glasgow initial est un facteur pronostic important. La gravité des signes cliniques est fonction du siège d’atteinte cérébrale et des lésions vasculaires endocrâniennes associées. Les infections et les lésions vasculaire intracrâniennes sont les principales complications à redouter.

Tableau I : Récapitulatif des cas de traumatisme crânien pénétrant par des clous de 2006 à nos jours.

Angio-TDM : angioscanner, M : masculin Angio-MR : angio-IRM NP : non précisé F : féminin TDM : tomodensitométrie (scanner) GCS : score de Glasgow

Articles récents

Commentaires récents

Archives

CatégoriesMéta |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

© 2002-2018 African Journal of Neurological Sciences.

All rights reserved. Terms of use.

Tous droits réservés. Termes d'Utilisation.

ISSN: 1992-2647