EDITORIAL (fr)L’étude récente de l’Institut de recherche et de développement (IRD)[1] intitulée « Diaspora scientifique : comment les pays en développement peuvent-ils tirer parti de leurs chercheurs et de leurs ingénieurs expatriés ? » interpelle tous les acteurs et spectateurs de la scène scientifique africaine. Les chiffres cités mettent dramatiquement à nu la pénurie d’hommes et de femmes susceptibles de s’investir dans la recherche au profit de ce continent qui a du mal à s’amarrer à la modernité. En effet, l’Afrique, où vit 10 % de la population mondiale, ne représente que 0,7 % des publications scientifiques mondiales, et 0,1 % des dépôts de brevets technologiques [2] . Par ailleurs, au moins 600.000 chercheurs et ingénieurs originaires d’Afrique, d’Amérique latine, d’Inde ou de Chine travaillent aux Etats-Unis, en Europe ou au Japon. Deux tiers des étudiants venus se former dans un pays du Nord y restent définitivement. « L’afflux des cerveaux du Sud vers le Nord est un phénomène massif et durable » avertit la Direction générale de la coopération internationale et du développement [3] .

Les travaux de recherche des pays du Nord portent prioritairement sur des domaines essentiels pour leurs intérêts nationaux. La philanthropie n’est pas de mise et seul compte le bien-être des populations de ces pays. L’accélération du processus de mondialisation n’influe aucunement sur une triste réalité : les laboratoires de recherche de l’hémisphère Nord se « soucient comme d’une guigne » des problèmes spécifiques à l’hémisphère Sud. Les exemples abondent. Il suffit de rappeler le cas de la lutte contre les maladies parasitaires, notamment le paludisme. Cette maladie affecte près de 41% de la population mondiale, soit 2,3 milliards de personnes, et elle tue chaque année 1,5 à 2,7 millions de personnes, dont 1 million d’enfants de moins de 5 ans. Et pourtant, aucune amorce de solution n’a encore été ébauchée face à ce fléau de santé publique.

Pour le chercheur expatrié, l’exode vers les pays du Nord, pour des raisons économiques, socio-politiques, scientifiques, ou familiales est souvent vécu comme un véritable déchirement. Le cur et la raison interprètent cet éloignement comme un délit de non-assistance à personnes en danger. Mais une nouvelle approche émerge et la diaspora scientifique, qui était considérée comme une « perte sèche » pour le Sud, devient un atout pour les pays d’origine [4] .. Ainsi, les réseaux de chercheurs d’origine sud-américaine ont démontré que leur contribution au développement du pays d’origine peut être importante. Cette contribution peut prendre diverses formes : envoi de matériel et de documentation aux universités et aux centres de recherche locaux, identification de domaines d’études, mise en place de programmes tenant compte des possibilités scientifiques du pays d’origine, organisation de séminaires de formation, participation à des enseignements, accueil d’étudiants, montage de travaux de recherche, services consultatifs, etc.

Le monde scientifique africain doit s’inspirer de ces actions. A cet égard, il importe de mettre en place et d’activer un réseau de scientifiques de la diaspora africaine. La diffusion d’un Manifeste sur internet aiderait à l’élaboration d’une plate-forme d’action mobilisant des équipes autour de projets portant sur des thématiques de recherche appliquée traitant de spécificités africaines.

EDITORIAL (en)A recent paper of the French Institut de recherche et de développement(IRD)[1] entitled Science Diaspora: how can developing countries benefit from their expatriate researchers and scientists ? is of interest for all those who are involved in or spectators of the African scientific scene. The figures it mentions dramatically highlight how serious is the shortage of men and women science specialists working in research for the benefit of this continent, which is still struggling to be part of modernity. Africa, which has 10 % of the world’s population, produces only 0.7 % of the world’s scientific publications and 0.1 % of its registered patents[2]. Further, at least 600,000 researchers and engineers from Africa, Latin America, India or China are currently working in the United States, Europe or Japan. Of the students who go to seek training in a country of the North, two-thirds settle there permanently. The French office for international cooperation and development warns that “the influx of brains moving from the South to the North is a massive and durable phenomenon.”[3]

Research work in the developed countries of the North is focused on areas that are essential for their national interests. This is not a charity business, the only thing that counts is the well-being of their citizens. The increasing pace of globalization has no impact on a sad reality : research labs in the North have no interest in the specific problems of the South. Examples abound: parasitic diseases, including malaria, are a case in point. Malaria affects almost 41 % of the world’s population or about 2.3 billion people, and it kills, each year, between 1.5 ad 2.7 million humans, one million of them below the age of 5. However, not even the beginning of a solution is yet in sight to address this public health problem.

For an expatriate researcher who emigrates to the North for economic, socio-political, educational or family reasons, leaving is often a heartrending experience. Departure, says the heart and reason, is akin to a refusal to provide assistance to endangered persons. But a new approach is emerging, and expatriates from the South, who have been considered as a complete loss for the South, are becoming an asset for their home countries [4] . Thus, the networks established by researchers of South American origin have demonstrated that they can be an important contribution to development in their home countries. Such a contribution may take various forms : sending equipment and documentation to universities and local research centers, identifying useful areas of study, setting up of programs that take account of the scientific possibilities of the country of origin, organizing training seminars, giving courses, helping students, developing research projects, consultancy work, etc.

The science world in Africa should draw lessons from these actions. It is important to develop and activate a network of science specialists of the African diaspora. Publication on the internet of a Manifesto would help to develop a platform of action to mobilize teams of specialists on applied research projects specific to Africa’s needs.

NEURO-OPHTHALMOLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS OF HUMAN AFRICAN TRYPANOSOMIASISABSTRACT

Background

Human African trypanosomiasis is a re-emerging parasitic disease that affects the central nervous system and leads to severe neurologic manifestations in the late stage of the disease. Little is known about the prevalence of neuro-ophthalmologic disturbances in patients with human African trypanosomiasis (HAT).

Objectives

To determine the prevalence and the features of neuro-ophthalmologic abnormalities including the visual evoked potentials (VEPs) in HAT patients at the meningo-encephalitic stage prior to treatment.

Methods

Neuro-ophthalmologic examination was performed in 114 patients with neurologic involvement of HAT, of whom 110 underwent pattern reversal VEP recording.

Results

Neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations were observed in 32 patients (28%). Papilloedema (17%) and ocular motor nerve palsies (6%) mainly affecting the sixth cranial nerve were the most frequent neuro-ophthalmologic disorders. Visual field defects, cortical blindness and nystagmus were found in five, two and one patient respectively. In patients with cranial nerve palsies, the proportion of patients with papilledema was significantly greater than that of those without papilledema. A similar difference was observed between the proportion of patients with and that of those without parasite in CSF. VEPs were abnormal in 23% of the patients. The VEP abnormality consisted only of isolated P100 latency prolongation while the amplitude remained normal in all patients. VEPs were more likely to be abnormal in patients with papilloedema. There was no association between the prolongation of P100 latency and CSF biological parameters.

Conclusion

The most frequent neuro-ophthalmologic abnormalities in neurologically affected patients with HAT were those associated with increased intracranial pressure: papilloedema followed by cranial nerve palsies, mainly involving the abducens nerve. A few patients had pathological VEP despite apparently normal clinical examination. VEP is therefore a useful tool to detect subclinical impairment of the visual pathways in patients with HAT meningo-encephalitis.

Keywords : neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations, visual evoked potentials, human African trypanosomiasis

RESUME

Introduction

La trypanosomiase humaine africaine est une affection parasitaire qui affecte le système nerveux central et qui engendre des troubles neurologiques sévères au stade méningo-encéphalitique. Il n’existe cependant une rareté des données sur les manifestations neuro-ophthalmologiques de cette affection.

Objectifs

Déterminer la prévalence et décrire les caractéristiques des manifestations neuro-ophtalmologiques et des potentiels évoqués visuels chez les patients atteints de méningo-encéphalite à T. gambiense avant le traitement.

Methods

Un examen neuro-ophthalmologique a été réalisé chez 114 patients atteints de méningo-encéphalite à T.gambiense, parmi lesquels 110 ont fait l’objet d’un enregistrement des potentiels évoqués visuels.

Résultats

Les manifestations neuro-ophthalmologiques ont été observées chez 32 patients (28%). L’oedème papillaire (17%) et les paralysies des nerfs oculo-moteurs (6%) touchant principalement le nerf oculo-moteur externe étaient les manifestations neuro-ophtalmologiques les plus fréquentes. L’amputation du champs visuel, la cécité corticale et le nystagmus étaient observés respectivement chez 5, 2 et 1 patient. Dans le groupe des patients ayant des paralysies des nerfs crâniens, ceux avec papilloedème était significativement plus nombreux que ceux sans papilloedeme; la meme observation était faite en ce qui concerne la présence ou l’absence du parasite dans le LCR. Les potentiels évoqués visuels étaient pathologiques chez 23% des patients. Chez tous ces patients la latence était prolongée alors que l’amplitude était conservée. Le risque d’avoir un potentiel évoqué visuel pathologique était plus élevé chez les patients avec oedème papillaire. Il n’y avait aucune association entre la prolongation de la latence et les paramètres biologiques du LCR.

Conclusion

Les manifestations neuro-ophthalmologiques les plus fréquentes chez les patients atteints de méningo-encéphalite à T. gambiense sont celles associées à l’hypertension intracrânienne: oedème papillaire suive des paralysies oculo-motrices. Une petite proportion de patients ont des potentiels évoqués visuels pathologiques en dépit d’un examen clinique apparemment normal. Les potentiels évoqués visuels sont une bonne méthode pour détecter les atteintes subcliniques des voies visuelles chez les patients atteints de méningo-encéphalite à T. gambiense.

Mots clés: manifestations neuro-ophtalmologiques, potentiels évoqués visuels, trypanosomiase humaine africaine

INTRODUCTION

Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as sleeping sickness, is a parasitic disease caused by the T. brucei complex. It is an important public health problem in sub-Saharan Africa where it is associated with a high degree of suffering and mortality. In the West and Central Africa, it is caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense transmitted to humans through the bite of the tsetse fly (Glossina species). According to recent estimations 60 million people from 36 sub-Saharan countries are at risk of contracting the disease, while 300,000-500,000 people are already infested. The Democratic Republic of Congo is one of the most affected countries, accounting for 20% of the total population at risk in Africa. A combination of poor surveillance and no vector control has resulted in the re-emergence of the disease now reaching a very high prevalence (6, 11, 17, 19). It is believed that the population movement from and to the affected areas due to the ongoing unstable situation in the country contributes to the spread of the disease. Kinshasa, the capital, until recently considered to be free from the infection, is currently showing an alarming picture because of an increasing number of cases within the city (i.e. 433 and 912 cases reported in 1998 and 1999 respectively) (2). Clinically, the advanced stage of the disease, which has a chronic course, manifests by severe neurologic disorders after the parasite has invaded the central nervous system (CNS). HAT may induce different neuro-clinical pictures including pyramidal or extrapyramidal, brain stem, bulbar or pseudo-bulbar, superficial or profound sensitive, hypothalamic syndromes and intracranial hypertension.

Extensive studies have been conducted on HAT, but they mostly focussed on basic research. This may explain why apart from reports on isolate cases (3, 13, 20), data on neuro-ophthalmologic investigations in HAT are not available. Moreover the need for more clinical research in HAT has been recently emphasised (16).

The overall aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence and the features of both the neuro-ophthalmological manifestations and visual evoked potentials in neurologically affected patients with HAT. In addition, the study aimed at relating the clinical and VEP abnormalities to the biological parameters.

PATIENTS & METHODS

PATIENTS

Patients were recruited among those patients routinely detected by mobile trypanosomiasis teams in Kinshasa and surrounding rural areas and referred for further investigations to the trypanosomiasis ward at the Department of Neurology, Kinshasa University Hospital, which is the central point for all Trypanosomiasis treatment in the capital. Because of the potentially toxic and lethal effects of melarsoprol used to treat the second stage of HAT, referred patients routinely undergo a pre-treatment check-up during the first week of admission with the aim to ascertain the diagnosis and stage the disease. During this pre-treatment week the diagnosis of HAT is reconfirmed based on the identification of the parasite in blood, lymph nodes and /or the cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF). Involvement of the CNS (stage 2) is considered when at least one of the following criteria is met: 1) isolation of the parasite in the CSF, 2) the combination of a) presence of the parasite in blood or lymph node aspirate plus b) biochemical alterations of the CSF consisting of an increased leucocyte count (over 5 cells/mm3) and an increase in CSF protein (above 45 mg %) and c) an abnormal neurological examination, which may consist of isolated or combined signs of meningitis, frontal, pyramidal, extrapyramidal or cerebellar involvement. Other causes of infectious meningo-encephalitis notably malaria, tuberculosis, cryptococcosis, toxoplasmosis and HIV-infection are also routinely excluded before diagnosis of the second stage of HAT. CSF pressure was not established quantitatively.

This study included all newly detected and untreated patients with second stage of HAT during two periods: July-October 2001 and August-December 2002, a total of 114 patients. Their age ranged from 4 to 71 years (mean: 32 ± 14 years). Sixty-two (54%) of them were men. In 61 patients (54%) the parasite was found in the CSF.

METHODS

Neuro-ophthalmological examination

All patients with second stage of HAT underwent neuro-ophthalmological examination and VEP recording prior to any treatment. Visual acuity testing was performed with Snellen charts. The pupils were checked for size, shape and light responses, and upper lids checked for ptosis and retraction. Ocular motility and deviation, including ductions and versions in all cardinal positions of gaze, and the testing of convergence ability were also evaluated. Strabismus was assessed by cover-uncover and alternate-cover tests. Direct ophthalmoscopy with special attention on optic disc border and color, macula and foveal reflexes to exclude any apparent retinal disease that could interfere with the VEP results. Visual fields were quantified by Goldmann perimetry. Examination of the anterior segment of the eye by slit-lamp (Haag-Streit 900) biomicroscopy was also done.

VEP recording procedure

VEPs were recorded in the patients and controls. The controls consisted of 76 healthy subjects (36 males and 40 females) with a mean age of 25 ± 15 years (range: 8-58) recruited among relatives of the patients, medical students and medical staff. The preparations for the VEP recording were performed in a darkened room illuminated by a dim red lamp. The active electrode was placed in the midline just above the inion, the reference electrode placed on the midline 2 cm anteriorly, and the forehead used as ground. The VEPs were elicited monocularly with an alternating checkerboard pattern of black and white rectangles on a TV monitor (Philips, Italy) placed at a distance of 1 meter in front of the subject. Each check measured 1.71 degrees of visual angle horizontally and 0.85 degrees vertically. The luminances of the black and white checks were 2 and 90 cd/m2 respectively, with a contrast of 90%. The patients were asked to fixate constantly a central target placed on the TV screen. The recording was performed using a 2-channel equipment (Cadwell 5200A, USA). One hundred stimulus responses were averaged using the manufacturer’s setting scale of 4. Amplifier parameters were automatically set to a sensitivity of 20 µV/div, sweep speed at 20 msec/div and the repetition rate at 2.11/sec. Filters were set at 1 Hz low cut and 70 Hz high cut. The latency of the P100 component and the peak-to-peak amplitude of N75/P100 were measured for each eye. In addition the P100 latency and amplitude interocular differences were calculated. These values were compared by considering the control mean ± 2.5 SD as the upper and lower limits of normal values of each of the above parameters. All values not within the corresponding limits were considered as abnormal. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

We examined 114 HAT patients with neurologic involvement. The clinical examination diagnosed neuro-ophthalmologic disturbances in 32 patients (28%), Table 1. Neurological manifestations were grouped in five clusters: meningeal manifestations (i.e. headaches, stiff neck, Kernig and Brudzinski’s signs), extrapyramidal manifestations (muscular rigidity, tremor, akathisia, dystonia, akinesia, dyskinesia), pyramidal manifestations (i.e. exaggerated tendon reflexes, Babinski’s reaction, Mingazzini or Baré’s reactions), cerebellar manifestations (i.e. hypotonia, dysdiadochokinesia, intention tremor, past-pointing) and frontal manifestations (i.e. grasp, snout, root, and suck reflexes, change in personality consisting of inappropriate jocularity, loss of initiative and concern, akinetic mutism, disinhibition and general retardation) were diagnosed in these patients. Sixteen of them (50%) had manifestations from all five clusters, 12 (37%) had all but the manifestations from the pyramidal cluster and 4 (13%) had manifestations from three different clusters.

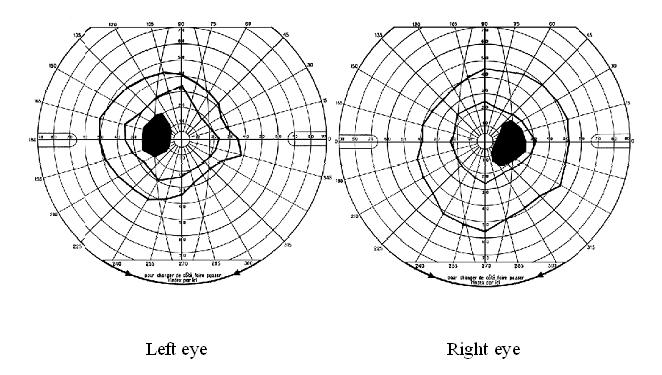

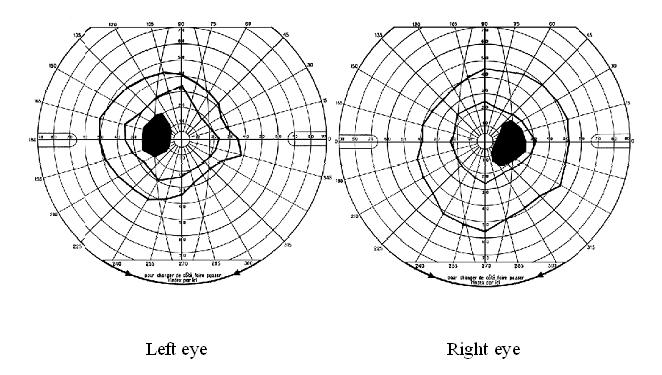

Papilloedema was the most common neuro-ophthalmologic disorder observed in 19 patients (17%). It was bilateral in all cases and only observed in those with severe involvement of the CNS based on the clinical picture. In 15 of them, it was the only neuro-ophthalmologic disorder. Cranial nerve palsies were present in 10 patients (9%) of whom 7 (6%) had unilateral ocular motor nerve palsies and 5 (4%) had facial nerve palsy. In the group of patients with cranial nerve palsies, there was a significant difference between the number of those with (n = 7) and without (n = 3) papilledema (p<0.05). Similarly, the number of those with (n = 9) was significantly greater than that of those without (n = 1) parasite in the CSF (p<0.05). Multiple ocular motor nerve palsies were present in a single case. Visual field defects, mostly consisting in concentric constriction, were observed in 4 patients (4%) though one had an enlarged blind spot in addition (Figure 1). Cortical blindness and a primary position horizontal jerk nystagmus were discovered in 2 and 1 patient, respectively.

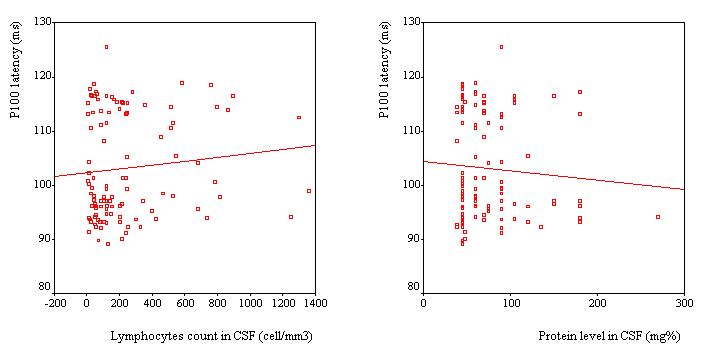

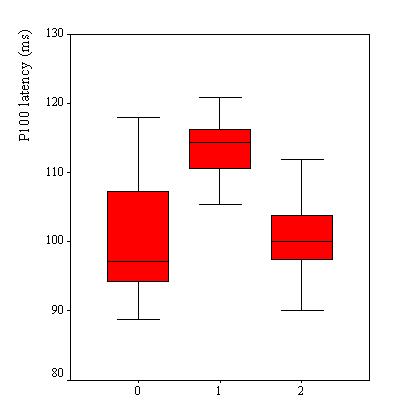

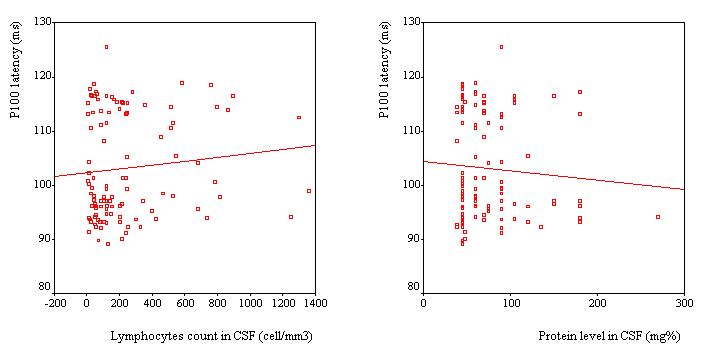

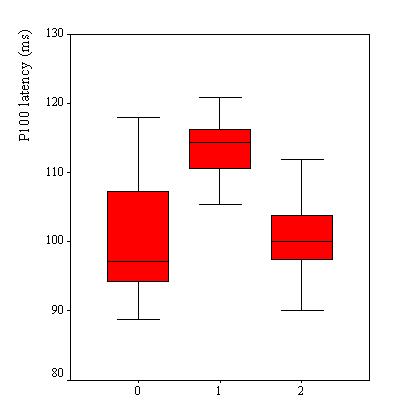

VEPs were recorded in 110 patients, Table 2. VEP was abnormal in 25 patients (23%). The P100 latency was bilaterally prolonged in 23 patients while the N75/P100 amplitude remained within the 95% confidence interval in all patients. However taken as a group, the mean P100 latency (102.8 ± 9.6 ms) was not significantly different as compared to the mean value of the controls (100.8 ± 5.2 ms) (p>0.05, C.I: -0.3-4.4). No significant difference was observed in the mean amplitude of the two groups of subjects (p =0.062). Among the 25 patients with abnormal VEPs, 9 (36%) had papilloedema in addition while the remaining had no papilledema. Sixteen subjects had prolonged VEP latency despite apparently normal optic discs. There were no association between P100 latency and CSF inflammatory parameters (lymphocyte count: p = 0.4 and protein level: p = 0.7), Figure 2. Patients with papilloedema had a significantly prolonged P100 latency (112.3 ± 6.6 ms) compared to those without papilloedema (100.7 ± 8.9 ms) (C.I.: 7.2-15.8) (Figure 3), and had four times the risk for having prolonged P100 latency than those without papilloedema (odds ratio = 4.2). In contrast, no significant difference was found between the mean P100 latency patients with (102.4 ± 9.9 ms) and those without (103.1 ± 9.2 ms) parasite in the CSF.

DISCUSSION

We here report the first systematic study of neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations in neurologically affected patients with HAT prior to treatment. In this series, 32 patients out of 114 (28 %) manifested with neuro-ophthalmologic abnormalities.

Papilloedema (17%) was the most common abnormality found in this series. Apart from the study by Dutertre (5) in France where papilloedema was found in 3 out of 19 (16%) patients coming from known endemic areas, most existing data on papilloedema in HAT are confined to isolated case reports. What is the pathogenic mechanism of papilloedema in HAT? In infectious meningo-encephalitis, papilloedema generally results either from optic neuritis following the direct effect of the infectious agent on the optic nerve or from raised intracranial pressure. The optic neuritis mechanism is questionable as no patients had symptoms or signs consistent with the diagnosis of optic neuritis in this series. The normality of the visual acuity and visual field observed in most patients also speaks against this mechanism. Moreover, although more recent experimental studies have demonstrated that trypanosomes cross the blood-brain barrier (7, 12), the presence of the parasite in the human brain parenchyma has not been proven (10). Since increased intracranial pressure is a well-known feature of the second stage of the disease, it is much more plausible that the papilloedema arises from raised intracranial pressure resulting from cerebral edema after the parasite has diffusely invaded CNS (4, 9).

The resulting rise of intracranial pressure is also likely to be the underlying cause of the observed cranial nerve palsies. Indeed, of the 10 patients with cranial nerve palsies 7 had papilledema. Since in HAT many structures of the brain are involved, it is also possible that some of the resulting lesions play a role in the occurrence of cranial nerve palsies, which are less commonly seen due to raised intracranial pressure alone, such as the third and sixth palsies. We therefore conclude that most of the neuro-ophthalmological pathologies seen are caused by raised intracranial pressure.

Although papilloedema was found to be a risk factor for delayed P100 latency, it was also observed in the present series that VEP were prolonged in some patients without papilloedema. The effects of high intracranial pressure on visual function have been studied by others investigators, in particular in benign intracranial hypertension. Prolonged latencies have been reported in 17-55% of cases (8, 14, 15, 18) and may precede disturbances of visual acuity and visual fields (15). This finding tends to suggest the presence of subclinical dysfunction in the visual pathways of patients with HAT. However the underlying mechanism has to be clarified, as is the case for some of the cranial neuropathies in HAT and other dysfunctions in the nervous system of the affected individuals. In HAT, demyelination of the brain has been reported in late stages both in vivo and in vitro (1, 5). However none of the studies has focused on the issue as to whether or not the process of the demyelination also involves the visual pathways, even though demyelination of the optic chiasm has been described in a single study (5). Since there is neither neuro-imaging nor autopsy evidence in this series, this pathogenetic mechanism cannot be firmly taken as the cause of the observed VEP abnormality. Nevertheless, a hypothesis can be put forward that morphological changes affecting the visual tract start early in some patients, and may differ from one patient to another, depending on some factors yet to be established. Pathological studies with special emphasis on the visual pathways on both humans and in experimental models are needed to help localize and characterize these changes.

The presence of the parasite in CSF was associated with neither papilloedema nor prolongation of P100 latency. This lack of association is in accordance with the fact that trypanosomes are not always found in CSF, despite the severity of the clinical manifestations.

To conclude the most frequent neuro-ophthalmologic abnormalities in neurologically affected patients with HAT observed in this study were likely to be associated with increased intracranial pressure and included papilloedema and cranial nerve palsies, most often the abducens nerve. VEPs were abnormal in some patients despite apparently normal clinical examination. P100 latency was prolonged while the N75/P100 amplitude remained normal. VEP is a useful tool to detect subclinical impairment of the visual pathways in patients with HAT and raises the question regarding the underlying neurologic damage in this disorder.

| ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS |

| We wish to thank Drs Mputu Anne-Marie and Nyamabo Louis for their assistance. We are also grateful to Professors Kayembe David and Kayembe Tharcisse, both at the Kinshasa University Hospital, for allowing the study to be conducted in their departments. This study was supported by Norwegian Agency for Development Co-operation and the University of Bergen. |

Table 1

| Manifestations |

|

|

N (%) |

Trypanosome in CSF (+) |

Trypanosome in CSF (-) |

CSF lymphocytes (<5ml) |

CSF lymphocytes (5-20ml) |

CSF lymphocytes (>20/ml) |

CSF protein (45-100 mg%) |

CSF protein(>100 mg) |

| Papilloedema |

|

|

19 (17) |

12 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

19 |

11 |

8 |

| Cranial nerve palsy |

|

|

10 (9) |

9 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

9 |

7 |

3 |

| |

-isolate |

|

8 (7) |

7 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

6 |

2 |

| |

|

VI |

5 (4) |

4 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

| |

|

VII |

3 (3) |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

| |

-multiple |

|

2 (2) |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

| |

|

VI+VII |

1 (1) |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| |

|

III+IV+VI |

1 (1) |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| Visual field defects |

|

|

5 (4) |

2 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

0 |

| Cortical blindness |

|

|

2 (2) |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

| Nystagmus |

|

|

1 (1) |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Number and percent of patients with different types of neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations in 114 neurologically affected patients with HAT. A total of 32 patients (28%) had any neuro-ophthalmological disturbances.

Table 2

| |

Controls |

HAT |

95% C.I. |

| Number of participants |

76 |

110 |

|

| Mean P100 latency ± SD (ms) |

100.7 ± 4.9 |

102.8 ± 9.6 |

-0.3-4.4 |

| Mean amplitude ± SD (uV) |

14.8 ± 5 |

13.4 ± 4.8 |

-2.8-0.07 |

VEP results in neurologically affected patients with HAT compared to controls.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

-

-

Figure 1

-

-

Figure 2

-

-

Figure 3

RESUME

Introduction

L’hyperexcitabilité neuronale observée dans les crises épileptiques serait la résultante d’un déséquilibre entre une inhibition par l’acide ?-amino butyrique (GABA) et l’excitation par le glutamate, en faveur de ce dernier.

Objectif

Le but de notre travail est de déterminer les taux sériques de glutamate, lactate, lacticodéshydrogénase et glutamine chez les épileptiques gabonais afin d’évaluer leur pouvoir informant dans le pronostic et le suivi des épilepsies dans notre environnement.

Méthodes

L’étude a porté sur 43 patients des deux sexes dont l’âge moyen est de 31,4±23,9 ans (avec des extrêmes allant de 2 à 75 ans) hospitalisés et vus en consultations externes, faisant principalement une crise par mois (76,7%) et une prédominance des crises généralisées (67,4%).

Résultats

Les étiologies les plus fréquemment retrouvées concernent les accidents vasculaires cérébraux (26,1%) et les infections (11,6%). Une augmentation nette des taux sériques de glutamate est observée, allant de 147 à 600 µmol/l, pour une moyenne de 351,7±119,6 µmol/l (normale : 40-120 µmol/l).

Conclusion

Cette étude préliminaire appelle des recherches complémentaires sur des séries longitudinales concernant les clairances hémato-méningées du glutamate pour bien cerner les problèmes d’excitotoxicité liés au glutamate.

Mots clés : Afrique, Epilepsie, Gabon, Glutamate

SUMMARY

Introduction

The neuronal excitability which can be observed during the epilepsial crisis should be the result of a disequilibrium between the inhibitory action of GABA (y-Amino Butyric Acid) and the excitatory action of glutamate, in favour of the latest.

Objectives

The main goal of our study is to determine the glutamate seral in Gabonese people suffering from epilepsy in order to evaluate their informative power for the pronostic and the follow-up of epileptic crisis in our environment.

Methods

The study has concerned 43 patients of both sexes whom medium age was 31,4±23,9 years (from 2 to 75 years old), hospitalised and from external consulting.

Results

Results obtained showed increased levels of seral glutamate (351,7±119,6 µmol/l, from 147 to 600 µmol/l (normal range from 40 to 120 µmol/l). This preliminary study needs to be completed with longitudinal assays of glutamate in order to improve the pronostic of epilepsy.

Keywords : Africa, Epilepsy, Gabon, Glutamate

INTRODUCTION

L’épilepsie est définie comme une affection caractérisée par la récurrence d’au moins deux crises convulsives non provoquées, survenant dans un laps de temps de plus de 24 heures. L’épilepsie est un véritable problème de santé publique dans les pays en voie de développement [9] où son incidence est près de deux fois plus élevée que dans les pays développés (113 – 119 pour 100.000 habitants par an contre 69 pour 100.000 habitants). Sa gravité est liée à sa mortalité qui est deux à trois fois celle de la population générale et à son caractère invalidant puisque le taux de récidive est estimé à 71% dans les trois ans qui suivent une première crise [5,6]. La rémission sous traitement survient dans 70 à 80% des cas, conduisant à arrêter le traitement. Cependant, le risque de rechute après arrêt du traitement est de 17-50% des cas. Actuellement, il n’existe pas de marqueurs fiables permettant de prédire le risque de récidive des crises épileptiques et ainsi, d’adapter la durée et la posologie du traitement prophylactique.

Le but de cette étude prospective a été de déterminer si les taux sériques d’un neurotransmetteur très impliqué dans la survenue de l’épilepsie, le glutamate, en relation avec les marqueurs directs et indirects de l’acidose (glutamine, lactate, lacticodéshydrogénase) étaient élevés chez les patients épileptiques avant tout traitement, et si cette élévation pouvait être corrélée avec le risque de récidive des crises épileptiques. La mise en évidence d’une telle corrélation pouvant avoir des implications thérapeutiques.

MATERIEL ET METHODES

Cette étude prospective a été réalisée entre février et août 2002 sur deux sites : le service de neurologie du Centre Hospitalier de Libreville (CHL) et le service de Neurochirurgie de la Fondation Jeanne Ebori (FJE). Les dosages biologiques ont été réalisés dans le Laboratoire de Biochimie de la Faculté de Médecine de Libreville et au Laboratoire Cerba Pasteur en France.

Les critères d’inclusion ont été: une épilepsie active, la survenue d’au moins deux crises convulsives, un électroencéphalogramme anormal, une glycémie normale, l’absence de drépanocytose et une numération formule sanguine normale.

Quarante trois patients des deux sexes, âgés de 2 à 75 ans ont été inclus dans l’étude. Chaque patient inclus (ou son entourage) était soumis à un interrogatoire complet, visant à déterminer l’ensemble des caractéristiques de l’épilepsie, puis subissait un examen général complet.

Les prélèvements sanguins ont été effectués sur tubes secs, EDTA et fluorure oxalate. Le glutamate et la glutamine ont été dosés par Chromatographie Liquide Haute Performance (HPLC) avec détection électrochimique, la LDH et les lactates par spectrophotométrie classique. Afin d’étudier la valeur pronostique du dosage sérique du glutamate et de la glutamine sur la fréquence des récidives, les patients ont été divisés en deux groupes :

– Groupe 1 (n = 17): patients ayant une crise épileptique ou moins par mois;

– Groupe 2 (n = 26): patients ayant présenté plus d’une crise épileptique par mois.

L’analyse statistique des données est réalisée à l’aide du logiciel EPI 6. L’analyse des variances (ANOVA), le Khi deux et le test non paramètrique H de Kruskal Wallis ont été les tests de comparaison utilisés. Les valeurs alpha <= 0,05 ont été considérées significatives.

RESULTATS

L’âge moyen de notre population d’étude est de 31,4±23,9 ans. Il y a 25 hommes (58,1%) âgés de 23,2±18,9 ans et 18 femmes (41,9%) âgées de 36,6±25,7 ans en moyenne. Il n’y a pas de différence significative entre ces deux groupes.

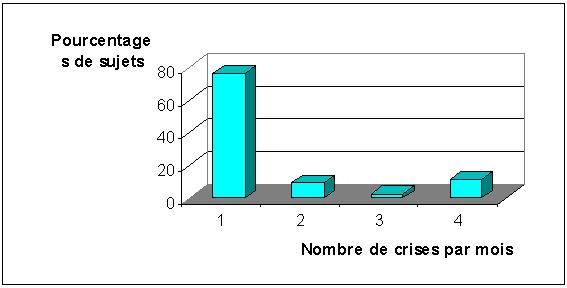

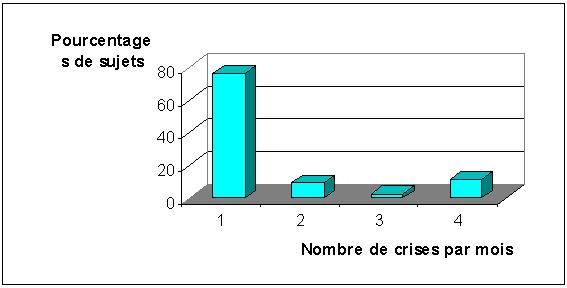

Les crises sont généralisées chez 29 patients (67,4%) et partielles chez 14 (33,6%). Elles surviennent une fois par mois chez 76,7% des patients, deux fois chez 9,3%, trois fois chez 2,7% et quatre fois chez 11,3% des patients (figure 1).

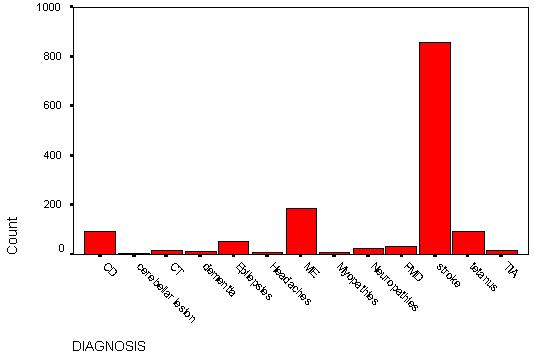

La fréquence mensuelle moyenne des crises est de 1,0±0 dans le groupe de malades hospitalisés versus 1,8±0,2 dans le groupe de malades non hospitalisés. La principale étiologie retrouvée est représentée par les accidents vasculaires cérébraux (Figure 2).

Les taux de glutamate dans le sérum de nos patients varient de 147 à 600 µmol/l, pour une moyenne de 351,7±119,6 µmol/l. L’intervalle de référence pour la technique utilisée est de 40 – 120 µmol/l. Tandis que les valeurs moyennes du glutamate des patients hospitalisés ne sont pas significativement différentes de celles des patients non hospitalisés (348,1±114,4 µmol/l, contre 356,0±128,7 µmol/l), avec p = 0,97.

Les valeurs de glutamine retrouvées dans l’échantillon sont normales ou relativement basses pour la plupart, la moyenne étant de 239,2±9 (98 – 399) µmol/l. Les valeurs normales pour la technique étant de 180 – 550 µmol/l.

Les valeurs de LDH varient de 158 à 650 U/I, avec une moyenne de 359±112 U/l. Les valeurs de LDH ne diffèrent pas significativement selon que les patients sont hospitalisés ou pas (p = 0,39). Il existe cependant une relation entre la LDH et la fréquence des crises (p=0,00).

Les valeurs des lactates varient de 2,1 à 15,5 mmol/l avec une moyenne de 5,8±3,1 mmol/l. La plupart des patents, 38 sur 43 (88,4%) ont des valeurs de lactates supérieures aux valeurs normales. Les valeurs normales chez les patients hospitalisés (6,0±3,8 mmol/l) ne diffèrent pas statistiquement de celles des patients non hospitalisés (p=0,92).

DISCUSSION

Dans les pays en voie de développement, presque toutes les études montrent une précocité dans l’installation de la maladie épileptique. A Dakar (Sénégal), 48,2% des épileptiques ont moins de 5 ans et les infections sont, avec 67%, l’étiologie la plus citée [3]. Dans les pays industrialisés, le début de l’épilepsie est moins précoce [11]. Dans notre étude, il existe deux pics de prévalence, situés aux extrémités de la vie, c’est-à-dire à 0 – 5 ans et 60 – 70 ans. Dans la première tranche d’âge, la précarité des conditions de suivi des grossesses, de la prise en charge périnatale, les infections materno-foetales, le paludisme, sont autant de causes et de circonstances favorisantes et/ou déclenchantes. Notre population comportait 13,95% d’enfants de moins de 5 ans et l’étiologie infectieuse n’est retrouvée que dans 11,6% des cas, contre 27,9% pour les AVC. Dans la dernière décennie de la vie, la sommation des effets socioprofessionnels tout au long de la vie, mais aussi des causes organiques peuvent justifier cette fréquence élevée.

La plupart des études épidémiologiques concernant les aspects cliniques dans les pays en voie de développement retrouvent une prédominance des crises généralisées, suivies des crises partielles puis les crises non classées. Les résultats de notre étude font ressortir une prédominance des crises généralisées tonicocloniques (67,4%), suivies des crises partielles (32,6%). L’écart avec les résultats des pays développés pourrait être dû à l’absence de données de l’EEG qui permettraient de mettre en évidence les foyers irritatifs et de faire le diagnostic d’une généralisation secondaire. Par conséquent, plusieurs crises étiquetées comme généralisées sont en fait des crises partielles secondairement généralisées [2].

Au plan biochimique, le glutamate est le neurotransmetteur majeur dans la genèse de l’excitabilité cellulaire et synaptique neuronale et le primum movens de l’excitotoxicité [8]. Son action s’accomplit via ses récepteurs et s’accompagne d’une entrée massive de Ca2+ à l’intérieur de la cellule. Cette action peut être médiée par le CO et le NO produits par la NO synthétase neuronale. L’effet direct de celui-ci est délétère, mais en particulier, il potentialise la toxicité du glutamate en entretenant une perfusion sanguine et une oxygénation excessive, conduisant à la formation du peroxynitrile (-OONO), oxydant cytotoxique. Quant au CO, il entretiendrait l’hyperhémie concomitante à l’épilepsie, régulant le débit sanguin, lequel est associé à une libération de glutamate. Dans notre étude, la concentration du glutamate est très élevée. Elle l’est aussi bien chez les malades hospitalisés que ceux vus en externe, sans différence significative entre les deux groupes (p=0,97). Ces taux très élevés de glutamate seraient justifiés par le fait que nous enregistrons 67,4% d’épilepsies généralisées et 32,6% d’épilepsies partielles qui peuvent secondairement se généraliser (21,2% dans une série de Dakar, dans lesquelles 60,5% sont tonico-cloniques et 2,3% myocloniques). On pourrait ainsi craindre en contexte infectieux (Sida, paludisme) et non infectieux (traumatisme, alcool) et en présence de circonstances favorisantes, qu’une interaction permanente avec des taux de glutamate décrochés ne soit un terrain de prédilection à la recrudescence des crises d’épilepsie. Gamberino [4] confirme en effet que l’élévation du taux de glutamate et le neuro-sida sont des circonstances d’une excitotoxicité génératrice d’une dégénérescence aiguë progressive.

Chez les individus normalement oxygénés et perfusés, la concentration des lactates varie de 0,5-2,5 mmol/l. Les occasions de privation ou de réduction de l’oxygénation des tissus telles l’hypoxie restent difficiles à détecter au lit du malade. Elles conduisent à l’augmentation de l’acide lactique et ont été largement décrites par de nombreux auteurs et ont mis en évidence l’intérêt du dosage de l’acide lactique [1,12].

Les travaux de Hazouar [7] sur la crise convulsive mettent en évidence un intérêt certain pour les dosages des lactates. L’acidémie lors de la crise convulsive est d’après lui, associée à une acidose métabolique. Cette acidose est le résultat d’une hypoxémie, d’une élévation critique des catécholamines et du métabolisme aéro-anaérobie musculaire pendant les crises tonico-cloniques. La signification clinicobiologique des lactates veineux périphériques est bonne pour l’aide au diagnostic de la crise généralisée. La disponibilité du lactate et le déficit énergétique pourraient entraîner une double destinée métabolique: la néoglucogenèse avec activation de la pyruvate décarboxylase, mais aussi la formation du glutamate [1] entraînant ainsi le cercle vicieux excitotoxicité – acidose. Dans notre étude, 88,4% des patients ont une lactatémie élevée. La lactatémie moyenne de nos patients est de 5,8±3,1 mmol/l. La lactatémie des malades hospitalisés ne diffère pas significativement de ceux vus en externe (p=0,92). La plupart des épileptiques de notre série (67,4%) font des crises tonico-clonique et myocloniques.

Le profil épidémiologique de notre population de travail où prédominent les AVC à un taux de 26,1 % (composante ischémique et séquellaire), les causes périnatales pour 16,3% (souvent attribuables aux infections dans notre terrain) et des infections (11,6%) justifient cette hyperlactatémie et l’entretiennent. On peut craindre alors un cercle vicieux dans la fréquence des crises avec des manifestations biologiques et électriques à bas bruit, suivis de crises patentes.

La LDH est un essuie glace métabolique entre le lactate et le pyruvate. Sa concentration suit le taux de lactate. En effet, Robinson [12] indique que dans les conditions d’hypoxie, le rapport NAD+/NADH a tendance à baisser dans la mitochondrie, à solliciter un équilibre avec le rapport NAD+/NADH cytosolique. Ce dernier va baisser à son tour, au détriment du NAD+. La forme réduite, NADH, sera prépondérante dans le cytosol, avec comme conséquence métabolique, la transformation préférentielle du pyruvate en lactate. Par ailleurs, il ressort de plusieurs études que le lactate étant produit en abondance en aérobiose et le pyruvate consommé, le rapport lactate/pyruvate se trouve élevé. De plus, ce pool de lactate va recevoir aussi celui qui diffuse des cellules sans mitochondries, à l’exemple des hématies. Tout ce qui précède explique l’augmentation de la LDH chez les patients de notre étude, mais aussi le degré de corrélation avec le lactate (p=0,00). Mieux, on a observé une relation particulière entre la fréquence des crises et le taux de LDH (p=0,00). Plus ce taux est élevé, plus le nombre de crises par mois est augmenté. La moyenne des crises chez les malades hospitalisés est de 1,8±1, contre 1,0 chez les non hospitalisés. Cette différence est significative (p=0,004). Certains de nos patients font même quatre crises par mois (11,3%).

De nombreuses études ont mis en évidence la baisse de la glutamine dans les maladies chroniques et son augmentation dans les états critiques [10], en particulier, dans le paludisme sévère, situation inductrice d’acidose par hyper lactatémie. Par contre, Wong [13] montre que son taux s’élève en particulier chez les enfants qui vont décéder au cours du paludisme grave ; cette élévation étant un mécanisme de lutte contre l’acidose. Dans notre étude, 37,2% des sujets ont des taux de glutamine bas. Les situations pre mortem n’y sont pas atteintes. La lutte contre l’acidose, mais aussi la formation préférentielle du glutamate pourrait expliquer cette baisse.

CONCLUSION

Dans cette étude prospective à visée physiopathologique, sur une série de 43 patients épileptiques, les principaux événements métaboliques mis en évidence dans ce travail concernent:

Au plan clinique et épidémiologique

– l’étiologie des crises (pathologies vasculaires, facteurs périnataux et infections)

– le type d’épilepsie (en majorité les crises généralisées dans 67,4% des cas)

– La fréquence des crises (jusqu’à 4 crises par mois chez 11 % des patients, pour une fréquence moyenne de 1,1).

Au plan biologique

– L’hyperglutamatémie (principal neurotransmetteur responsable de l’excitotoxicité)

– L’hyperlactatémie avec une faible décroissance (auto entretenue par l’association des étiologies suggestives de l’hypoxie)

– L’élévation des taux de LDH corrélée avec l’hyperlactatémie et la fréquence des crises, justifiées par la préférence de la voie métabolique allant du pyruvate au lactate.

Ce climat étiologique et métabolique est négatif pour l’environnement de l’épileptique gabonais car le mécanisme « kindling », d’excitabilité à bas bruit des structures musculaires et neuronales métabotropiques constitue une source permanente de l’avènement des crises classiques.

Enfin, des recherches complémentaires sur des séries longitudinales concernant les clairances hémato-méningées seront nécessaires pour étayer les notions de pronostic suggérées par le glutamate, les lactates et la LDH.

FIGURE 1 : Fréquences mensuelles des crises

#gallery-2 {

margin: auto;

}

#gallery-2 .gallery-item {

float: left;

margin-top: 10px;

text-align: center;

width: 33%;

}

#gallery-2 img {

border: 2px solid #cfcfcf;

}

#gallery-2 .gallery-caption {

margin-left: 0;

}

/* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

#gallery-2 {

margin: auto;

}

#gallery-2 .gallery-item {

float: left;

margin-top: 10px;

text-align: center;

width: 33%;

}

#gallery-2 img {

border: 2px solid #cfcfcf;

}

#gallery-2 .gallery-caption {

margin-left: 0;

}

/* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

-

-

FIGURE 1 : Fréquences mensuelles des crises

-

-

FIGURE 2 : Principales étiologies retrouvées

ABSTRACT

Background

The Niger-delta area of Nigeria constitutes about 20% of the population of the nation. The pattern of neurologic diseases in this area is not known.

Objective

The study was undertaken to determine the pattern of these diseases, compare this with those elsewhere and to have a baseline for future studies.

Methods

The medical records of all cases admitted with neurologic diseases in the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH) Port Harcourt between April 1993 and March 2003 were retrospectively reviewed and the frequency of neurologic diseases, sex, age and outcome of these diseases analyzed.

Results

Neurologic diseases constituted 1.5% and 33.1% of hospital and medical admissions respectively with M: F ratio of 1.4:1 and mean age of 52.6 years. The five topmost diseases were stroke (61.6%), meningitis and encephalitis (13.4%), tetanus (6.5%), spinal cord diseases (6.5%) and epilepsy (3.8%). Apart from stroke, the others were commoner in the young. Other neurologic diseases were rare causes of neurologic admissions. Neurologic deaths constituted 3.7% and 28.9% of hospital and medical deaths respectively. The common causes of neurologic deaths were stroke (65%), meningitis and encephalitis (18.7%) and tetanus (8.5%).

Conclusions

Neurologic diseases are common in this part and have a similar pattern as in other parts of southern Nigeria. Stroke and CNS infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. This finding makes the establishment of regional stroke units; improvement of the sanitary conditions of the home and environment, widespread use of immunizations for those at risk a matter of urgent healthcare priority.

Keywords : Africa, Epidemiology, Neurologic disease, Neurology, Nigeria, Stroke units

RESUME

Introduction

Le Delta du Niger constitue environ 20 % environ de la population du Nigeria, et le profil des affections neurologiques de cette région n’est pas connu.

Objectif

L’étude présentée a pour but de déterminer les aspects de ces maladies neurologiques en les comparant avec celles menées par d’autres équipes. Le travail servira de base pour mener d’autres études ultérieures.

Méthode

Les données médicales de tous les cas admis à l’université de Port Harcourt entre avril 1993 et mars 2003 ont été examinées rétrospectivement à partir des dossiers d’hospitalisation. La fréquence de maladie neurologique, le sexe, l’âge et l’évolution ont été analysés.

Résultats

Les maladies neurologiques représentent 1,5 % et 33,1 % des admissions respectivement en hospitalisation et sur l’ensemble de la pathologie médicale. Le ratio homme / femme est de 1,4 : 1 avec une moyenne d’âge de 52,6 ans. Les cinq maladies les plus fréquemment observées ont été : les accidents vasculaires cérébraux (61,6 %, les méningites et encéphalites (13,4 %) le tétanos (6,5 %), les maladies de la moelle épinière (6,5 %) et les épilepsies (3,8 %). En dehors des accidents vasculaires cérébraux, ces affections sont communes aux jeunes. Les autres affections neurologiques sont rares. Les décès imputables à la pathologie neurologique représentaient 3,7 % et 28,9 %, respectivement au niveau hospitalier et au plan médical.

La cause de décès la plus importante a été les accidents vasculaires cérébraux suivis des méningites et encéphalites (18,7 %) et tétanos (8,5 %)

Conclusion

Les affections neurologiques habituellement rencontrées ont un aspect similaire à celles observées dans le sud du Nigéria. Les AVC et les affections du système nerveux sont les principales causes de morbidité et de mortalité. Ces données impliquent la mise en place d’unités régionales d’AVC de même que l’amélioration des conditions sanitaires de l’environnement et de l’habitat et l’élargissement des vaccinations.

Mots-clefs : Afrique, maladies neurologiques, Nigéria, unité d’urgence neuro-vasculaire, épidémiologie.

INTRODUCTION

The Niger-delta extends over an area of about 70,000km2 and accounts for 7.5% of Nigeria’s land mass. It covers a coastline of 560km, about a third of the entire coastline of Nigeria, traversing nine states (Abia, Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, Edo, Imo, Ondo and Rivers) of the 36 states of the country with an estimated population of 20 million (1). The predominant occupation in the area are farming and fishing, with the oil sector as the main industrial base and responsible for over 90% of the nation’s export earnings. Port Harcourt, the Rivers State capital is the official capital of this area and harbors one of the four teaching hospitals in this area. Only two of these hospitals have the CT scan facility and there is no facility for the MRI. There are only two neurologists in this area. This study was conducted in the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH), a 484-bed tertiary referral center, with catchments area covering Rivers, Bayelsa, Abia, Akwa Ibom, Imo and parts of Cross River states and has an annual admission rate of 10,000 (2).

The hospital started active clinical services at its present temporary site in 1984. The Neurology Unit of the Department of Medicine was only recently created with the installation of a CT Scanning facility in the hospital in 2002. The pattern of neurologic admissions in this area is not known.

This study was therefore undertaken to determine the pattern of these diseases, compare it with those elsewhere in the country and also serve as a baseline for proper planning of the new unit and a yardstick for future studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The records of all medical admissions between April 1993 and March 2003 were collected from the medical wards and the medical records department of the hospital. Admission into the medical wards is from age of 14 years, so patients below this were not included. Figures of hospital admissions and deaths during the same period were also collected from the medical records department. Cases admitted for purely neurologic disorders were extracted for the study. The following data were extracted from these patients’ records – age, sex, date of admission, diagnosis, date of discharge and outcome (whether discharged, died, discharged against medical advise or absconded, or referred to other tertiary centers or departments). These data were then analyzed. The neurologic diseases were grouped into the following diseases: stroke, TIAs (transient ischemic attacks), meningitis (bacterial, included tuberculous and viral) and encephalitis (viral, included rabies), spinal cord diseases (included Pott’s disease, cervical and lumbar spondylosis, and disc disease), tetanus, Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders (included tremors, dystonias and dyskinesias), epilepsies, cerebellar syndromes, primary CNS tumors, neuropathies (cranial, autonomic and peripheral neuropathies included diabetic neuropathies), myopathies and neuromuscular disorders (included muscular dystrophies, polymyositis and myasthenia gravis), primary dementias and the primary headaches (migraine, cluster and tension headaches).

The diagnoses were made clinically in the majority of the patients, with laboratory confirmation in a few. The laboratory tests, depended on the suspected neurologic disease process and included complete blood count, ESR, serum biochemistry, ECG, x-rays, serological tests, microbiology, histopathology. CT scanning was used in a very small minority of patients since it became available only in 2002 and also because of affordability. The EEG, nerve conduction studies, EMG, carotid angiography, viral studies, histochemistry and other higher technology neurologic investigative tools were not utilized in the diagnoses of these patients because these facilities were not available. Lumbar puncture and muscle biopsies were used where these were indicated.

RESULTS

A total of 1,748 patients were admitted with neurologic disorders during the period under review out of which 1393 cases had sufficient data to be included into the study. The frequency of sex, age, morbidity and outcome of neurologic diseases were analyzed. Neurologic diseases constituted 1395 (33.1%) of 4213 medical admissions and 1.5% of 92,544 hospital admissions while in terms of mortality, they constituted 509(28.9%) of 1,759 medical deaths and 3.7% of 13,933 hospital deaths. The sex distribution of patients was 810 (58.1%) males and 585 (41.9%) females (Table 2), giving a sex ratio (M: F) of 1.4:1. The ages of the patients ranged from 14 – 110 years with a mean of 52.6 years. The mean age for males and females was 51.5 years and 54.1 years respectively. The shortest duration and longest duration of hospitalization was 1 day and 254 days respectively with a mean of 16.08 days. The mean duration of hospitalization for males and females was 15.05 and 17.49 days respectively. With regards to outcome, 787 (56.4%) of the patients were discharged, 509 (36.5%) died, 81 (5.8%) were discharged against medical advise (DAMA) or absconded and 16 (1.1%) were referred to other tertiary centers or our surgery department in the hospital. A summary of the above findings is shown in Table 1.

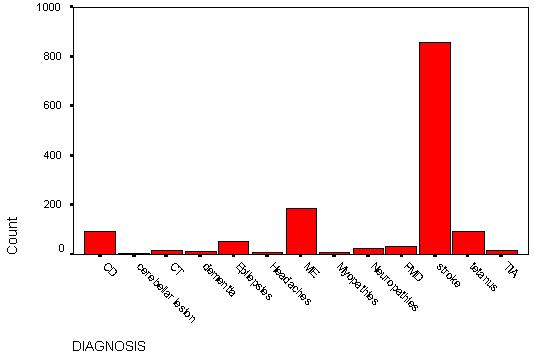

The frequency and the sex distribution of the various neurologic diseases as grouped above are shown in Tables 3, Fig. 1 and Table 4 respectively. Table 5 and Fig. 2 show the respective frequency of age ranges of the neurologic diseases individually and collectively. The frequency of admissions and deaths in relation to medical and hospital admissions and deaths are shown in tables 6. Tables 7 – 15 show the outcome neurologic diseases, as a whole and individually. The duration of hospitalization of these patients is on Tables 16 and 17.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that neurologic diseases are common in the Niger-delta area of Nigeria. These diseases included stroke, TIAs, meningitis (mainly bacterial, including tuberculous meningitis and viral) and encephalitis (mainly viral including rabies), spinal cord disorders (mainly Pott’s disease, cervical and lumbar spondylosis, and disc disease), tetanus, Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders (mainly tremors, dystonias and dyskinesias), epilepsies, cerebellar syndromes, primary CNS tumors, neuropathies (mainly cranial, autonomic and peripheral neuropathies, including diabetic neuropathies), myopathies and neuromuscular disorders(included muscular dystrophies, polymyositis and myasthenia gravis), primary dementias and primary headaches (migraine, cluster and tension headaches). These diseases constituted 1.5% of all hospital admissions and 33.1% of medical admissions. There was no significant sex predominance in these diseases as a whole. The mean age of the patients was 52.6 years with a slightly lower mean age in males. The highest peak age range of cases was between 60 to 64 years. The frequency of occurrence revealed that stroke (mainly cerebral infarction), infections (meningitis, encephalitis and tetanus), spinal cord diseases and epilepsies were the most common neurological disorders admitted with frequency rates of 61.6%, 19.9%, 6.5% and 3.8% of all neurologic admissions respectively. These four major disorders constituted 91.8% of all neurologic cases admitted. It was also noted that four of the cases of viral encephalitis had rabies, all of who died. Pott’s disease was the predominant cause of spinal cord diseases (31%). Other less common neurologic diseases were Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders 2.2%, neuropathies 1.8%, TIAs 1.2%, CNS tumors 1.1%, primary dementias 0.8%, primary headaches 0.4%, myopathies and neuromuscular disorders 0.5% and cerebellar diseases 0.3%. All these represented only 8.2% of the neurologic admissions. Parkinson’s disease constituted 83.3% of cases in the group of patients with movement disorders.

The above findings compare with those of Talabi (3) in UCH, Ibadan who reported frequencies of: stroke (50.4%), tetanus (14.2%), meningitis (12.4%) and myelopathies (8.1%). These disorders and seizures were reported as the most common neurologic diseases in that study. The difference in frequency rates in the two studies may be related to the difference in the duration of the study periods. The overall outcome of neurologic diseases showed that 787 (56%) were discharged, 509 (36.5%) died, 81(5.8%) were discharged against medical advice or absconded and 16 (1.1%) were referred to other hospital departments or tertiary centers. The death rate represented 28.9% and 3.7% of medical and hospital deaths respectively. The duration of hospitalization of patients with neurologic diseases was usually long, ranging from less than one day observed mainly in patients who died soon after admission, to 254 days, with a mean of 16.08 days. Females had a longer period of hospitalization (mean 21.37 days) than males (mean 16.04 days).

The age and sex distribution, outcome and period of hospitalization for the different types of neurologic diseases also varied. For the most common neurologic diseases, the following were observed:

Stroke – The peak age of admission was 60 to 64 years. This was in keeping with previous findings that stroke is a disease of the elderly in this environment (4) as is elsewhere (5), in contrast to earlier reports that stroke was more common below the age of 50 in the African (6,7). This trend may be related to the improving standard of living and longevity in our environment. However, when compared with Caucasians, a higher proportion of relatively younger Africans and Asians appear to suffer from stroke (8). There was a slight male preponderance (M: F=1.2:1) as had been noted previously (9). In terms of outcome, 468 (54.5%) of stroke admissions were discharged, 331 (38.5%) died, 52 (6.1%) were discharged against medical advice and 6 (0.7%) were referred. This stroke mortality represented 65% of neurologic deaths, 18.8% medical deaths and 2.37% hospital deaths. This shows that stroke mortality is quite high in this environment. Previous workers have also observed this finding. Odia and Wokoma (10) reported that cerebrovascular disease was the most common cause of deaths in the medical wards of UPTH, accounting for 15.9% of medical deaths. In Lagos Nigeria, Adegabite et al (11) noted stroke mortality of 36.5% and in Ibadan Nigeria; Adetuyibi et al (12) also observed that stroke was the commonest cause of neurologic deaths. The mean duration of hospitalization of stroke patients was 16.5 days.

Meningitis and encephalitis – This condition was also noted to be a significant cause of neurologic admissions and affected mainly the younger age group, with the highest age peak occurring in the age-range 15 to 19 years with a sex ratio (M: F) of 1.6:1. In the cases with this condition, 79 (42.2%) were discharged, 95 (50.8%) died, and 13 (7%) were discharged against medical advice. This group of patients recorded the highest mortality of 50.8%, although this represented 18.7% of neurologic deaths, 5.4% of medical deaths and 0.68% of hospital deaths. This mortality rate was very high when compared with that reported by Peters et al (13) in Calabar who recorded 19 (28.8%) deaths out of 66 cases studied. Their study however, did not include cases with encephalitis and was over a 5-year period. The mean duration of hospitalization of these patients was also the shortest (10 days), second only to patients admitted with TIAs. This was probably related to the high mortality rate.

Tetanus – This was another infective condition of the CNS affecting mainly the younger population. The peak age range affected was 20 to 24 years with a male predominance (M: F=2:1). In this group of patients, 45 (50%) were discharged, 43 (47.8%) died, 1 (1.1%) was discharged against medical advise and 1 (1.1%) was referred. The mortality represented 8.5% of neurologic deaths, 2.4% medical deaths and 0.31% hospital deaths. The high mortality rate noted in this group of patients is well known(14) and this is related to the low immunization rates of the population, late presentation, and inadequate intensive care facilities. The mean duration of hospitalization among these patients was 13.4 days.

Spinal cord diseases – The most common disease in this group was Pott’s disease and this was also more prevalent among the younger patients, with peak age-range 25 to 29 years and a sex ratio (M: F) of 1.8:1. Sixty-one (67%) of the cases were discharged, 15 (16.5%) died, 8 (8.8%) were discharged against medical advise and 7 (7.7%) were referred. The major cause of death was complicating secondary infections. The mortality represented 2.9% neurologic deaths, 0.9% medical deaths and 0.11% hospital deaths. This group of patients had the longest duration of hospitalization ranging from 1 day to 254 days, as they were usually bedridden, with a mean of 30.5 days.

Epilepsies – Majority of the patients in this group were also young with peak age-range 30 to 34 years and most had idiopathic epilepsy and were admitted with status epilepticus. There was no significant sex predilection. Forty (75.5%) of cases were discharged, 10 (18.5%) died and 3 (5.7%) were discharged against medical advise. Mortality was mainly due to status epilepticus and represented 1.9% neurologic deaths, 0.5% medical deaths and 0.07% hospital deaths. The mean duration of hospitalization was 13.2 days.

CONCLUSION

The Niger-delta area of Nigeria is unique in geography but not in the pattern of neurologic diseases. Stroke mainly cerebral infarction, is the commonest neurologic admission and the commonest cause of neurologic and medical death in this area as is noted elsewhere. Nearly two-fifths of stroke patients die. Infections of the central nervous system mainly meningitis, encephalitis and tetanus is the next common cause of admission and affect mainly the younger population. This group of diseases was also noted to have the highest mortality rate (mean 49.3%). Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders, neuropathies, TIAs, CNS tumors, primary dementias and headaches, myopathies and neuromuscular disorders, and cerebellar disorders were rare causes of neurologic admissions in this area.

In view of the above findings, the provision of a regional stroke unit with modern primary, secondary (including standard Intensive Care Units) and tertiary intervention facilities; the improvement of the sanitary conditions of the home and environment; the widespread use of immunizations against meningitis, tetanus and rabies for those at risk, cannot be over-emphasized. These interventions will to cut down drastically the scourge caused by stroke and CNS infections.

| ACNOWLEGEMENTS |

| My gratitude goes to the Almighty God for His mercies and Guidance; to the Matron, Dept of Medicine and the staff of the Medical Records Dept of UPTH, Port Harcourt for their assistance in the collection of the data and finally to my family for ensuring a conducive study environment at home. |

TABLE 1 – Summary of major findings

| TOTAL NO. NEUROLOGIC ADMISSIONS |

1748 |

| TOTAL NO. OF PATIENTS INCLUDED IN THE STUDY (I.E.TOTAL NEUROLOGICAL ADMISSIONS) |

1395 |

| TOTAL NO. OF PATIENTS EXCLUDED FROM THE STUDY |

353 |

| TOTAL NEUROLOGIC DEATHS |

509 |

| TOTAL HOSPITAL ADMISSIONS |

92,544 |

| TOTAL HOSPITAL DEATHS |

13,933 |

| TOTAL MEDICAL ADMISSIONS |

4,213 |

| TOTAL MEDICAL DEATHS |

1759 |

| % MEDICAL ADMISSIONS OF HOSPITAL ADMISSIONS |

4.6% |

| % NEUROLOGIC ADMISSIONS OF HOSPITAL ADMISSIONS |

1.5% |

| % NEUROLOGIC DEATHS OF HOSPITAL DEATHS |

3.7% |

| % NEUROLOGIC ADMISSIONS OF MEDICAL ADMISSIONS |

33.1% |

| % NEUROLOGIC DEATHS OF MEDICAL DEATHS |

28.9% |

| MEAN AGE OF NEUROLOGIC PATIENTS |

52.6YRS |

| MEAN AGE (MALES) |

51.5YRS |

| MEAN AGE (FEMALES) |

54.1YRS |

| MEAN DURATION OF HOSPITALIZATION OF ALL PATIENTS |

16.07 DAYS |

| MEAN DURATION OF HOSPITALIZATION (MALES) |

15.05 DAYS |

TABLE 2 – Sex frequency

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Female |

585 |

41.9 |

41.9 |

41.9 |

| Male |

810 |

58.1 |

58.1 |

100.0 |

| Total |

1395 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

TABLE 3 – Frequency distribution of neurologic diseases (also see Fig 1).

| NEUROLOGICDISEASES |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Cord diseases (CD) |

91 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

| Cerebellar lesions (CL) |

4 |

.3 |

.3 |

6.8 |

| Dementia (D) |

11 |

.8 |

.8 |

7.6 |

| Meningitis & encephalitis (ME) |

187 |

13.4 |

13.4 |

21.0 |

| Primary headaches (H) |

6 |

.4 |

.4 |

21.4 |

| Myopathies (MP) |

7 |

.5 |

.5 |

21.9 |

| Parkinson’s disease/Movement disorders (PMD) |

30 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

24.1 |

| Neuropathies (N) |

25 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

25.9 |

| Epilepsies (E) |

53 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

29.7 |

| CNS Tumors (CT) |

15 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

30.8 |

| Stroke (STR) |

859 |

61.6 |

61.6 |

92.3 |

| Tetanus (TET) |

90 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

98.8 |

| Transient ischemic attacks (TIA) |

17 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

100.0 |

| TOTAL |

1395 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

TABLE 4 – Sex frequency of Neurologic diseases.

| DIAGNOSIS |

SEX (F) |

SEX (M) |

Total |

| Cord diseases |

33 |

58 |

91 |

| Meningitis & encephalitis |

71 |

116 |

187 |

| Myopathies |

2 |

5 |

7 |

| Parkinson’s disease/Movement disorders |

7 |

23 |

30 |

| Neuropathies |

7 |

18 |

25 |

| CNS Tumors |

5 |

10 |

15 |

| Transient ischemic attacks |

7 |

10 |

17 |

| Cerebellar lesions |

|

4 |

4 |

| Dementia |

6 |

5 |

11 |

| Primary headaches |

5 |

1 |

6 |

| Epilepsies |

26 |

27 |

53 |

| Stroke |

386 |

473 |

859 |

| Tetanus |

30 |

60 |

90 |

| TOTAL |

585 |

810 |

1395 |

TABLE 5 – Age-range distribution of neurologic diseases

| AGE GRP |

CASE NO. |

CD |

ME |

MP |

PMD |

N |

CT |

TIA |

CL |

DEM |

H |

E |

STR |

TET |

TOTAL |

| <15y |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

| 15-19 |

2 |

8 |

37 |

|

1 |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

15 |

66 |

| 20-24 |

3 |

6 |

25 |

2 |

|

4 |

1 |

|

|

|

2 |

6 |

2 |

21 |

69 |

| 25-29 |

4 |

12 |

27 |

|

|

4 |

1 |

|

|

|

2 |

5 |

1 |

16 |

68 |

| 30-34 |

5 |

7 |

18 |

1 |

|

4 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

9 |

12 |

8 |

61 |

| 35-39 |

6 |

4 |

14 |

|

1 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

2 |

30 |

6 |

65 |

| 40-44 |

7 |

8 |

13 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

2 |

|

|

1 |

4 |

53 |

11 |

97 |

| 45-49 |

8 |

8 |

10 |

|

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

71 |

4 |

100 |

| 50-54 |

9 |

5 |

10 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

4 |

113 |

1 |

142 |

| 55-59 |

10 |

7 |

7 |

|

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

|

6 |

98 |

3 |

128 |

| 60-64 |

11 |

8 |

8 |

1 |

10 |

|

2 |

3 |

|

2 |

|

5 |

123 |

3 |

165 |

| 65-69 |

12 |

7 |

8 |

|

3 |

1 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

1 |

110 |

1 |

138 |

| 70-74 |

13 |

7 |

4 |

|

2 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

7 |

109 |

|

131 |

| 75-79 |

14 |

1 |

2 |

|

3 |

|

|

2 |

|

4 |

|

|

70 |

|

82 |

| >79 |

15 |

3 |

3 |

|

4 |

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

67 |

1 |

81 |

| TOTAL |

|

91 |

187 |

7 |

30 |

25 |

15 |

17 |

4 |

11 |

6 |

53 |

859 |

90 |

1395 |

CD=cord diseases

ME=meningitis & encephalitis

MP=myopathies, PMD=Parkinsonu2019s disease/movement disorders

N=neuropathies

CT=CNS tumors

TIA=transient ischemic attack

CL=cerebellar lesions

DEM=dementia

H=primary headaches

E=epilepsies

STR=stroke

TET=tetanus

TABLE 6 – Frequency of admissions and deaths of neurologic diseases in relation to medical and hospital admissions and deaths.

| DISEASE |

ADMS |

%NA |

DTHS |

%ND |

%MA |

%MD |

%HA |

%HD |

| STROKE |

859 |

61.6 |

331(38.5%) |

65.0 |

20.4 |

18.8 |

0.93 |

2.37 |

| MENINGITIS & ENCEPHALITIS |

187 |

13.4 |

95(50.8%) |

18.7 |

4.4 |

5.4 |

0.20 |

0.68 |

| CORD DISEASE |

91 |

6.5 |

15(16.5%) |

2.9 |

2.2 |

0.9 |

0.10 |

0.11 |

| TETANUS |

90 |

6.4 |

43(47.8%) |

8.5 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

0.10 |

0.31 |

| EPILEPSIES |

53 |

3.8 |

10(18.9%) |

1.9 |

1.3 |

0.5 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

| PD/MD |

30 |

2.2 |

5(16.7%) |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

0.03 |

0.04 |

| NEUROPATHIES |

25 |

1.8 |

2(8.0%) |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

| TIA |

17 |

1.2 |

0 |

0 |

0.4 |

0 |

0.02 |

0 |

| CNS TUMORS |

15 |

1.1 |

7(46.7%) |

1.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

| DEMENTIA |

11 |

0.8 |

1(9.1%) |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

| HEADACHES |

6 |

0.4 |

0 |

0 |

0.1 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

| MYOPATHIES |

7 |

0.5 |

0 |

0 |

0.1 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

| CEREBELLAR LESIONS |

4 |

0.3 |

0 |

0 |

0.1 |

0 |

0.004 |

0 |

| TOTAL |

1395 |

100% |

509(36.5%) |

100% |

33.1% |

28.9% |

1.51% |

3.65% |

ADMS=admissions

DTHS=deaths

NA=neurologic admissions

ND=neurological deaths

MA= medical admissions

MD=medical deaths

HA=hospital admissions

HD=hospital deaths

TABLE 7 – Outcome of all neurologic diseases

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

608 |

43.6 |

43.6 |

43.6 |

| |

Discharged |

787 |

56.4 |

56.4 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

1395 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

886 |

63.5 |

63.5 |

63.5 |

| |

Died |

509 |

36.5 |

36.5 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

1395 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

1298 |

93.0 |

93.0 |

93.0 |

| |

DAMA |

81 |

5.8 |

5.8 |

98.9 |

| |

Referred |

16 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

1395 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

TABLE 8 – Stroke outcome

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

528 |

61.5 |

61.5 |

61.5 |

| |

Died |

331 |

38.5 |

38.5 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

859 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

391 |

45.5 |

45.5 |

45.5 |

| |

Discharged |

468 |

54.5 |

54.5 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

859 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

801 |

93.2 |

93.2 |

93.2 |

| |

DAMA |

52 |

6.1 |

6.1 |

99.3 |

| |

Referred |

6 |

.7 |

.7 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

859 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

TABLE 9 – Cord diseases outcome

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

30 |

33.0 |

33.0 |

33.0 |

| |

Discharged |

61 |

67.0 |

67.0 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

91 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

76 |

83.5 |

83.5 |

83.5 |

| |

Died |

15 |

16.5 |

16.5 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

91 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

76 |

83.5 |

83.5 |

83.5 |

| |

DAMA |

8 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

92.3 |

| |

Referred |

7 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

91 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

TABLE 10 – Epilepsies outcome

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

43 |

81.1 |

81.1 |

81.1 |

| |

Died |

10 |

18.9 |

18.9 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

53 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|

13 |

24.5 |

24.5 |

24.5 |

| |

Discharged |

40 |

75.5 |

75.5 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

53 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| |

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

|