|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

RESUME La neuropathie sensitive congénitale est une affection rare. Nous rapportons le premier cas diagnostiqué au Sénégal. Il s’agissait d’une fillette de 30 mois qui présentait une insensibilité à la douleur, des ulcérations et cicatrices multiples en rapport avec des traumatismes. Les parents étaient cousins germains. L’éléctroneuromyographie montrait un effondrement des vitesses de conduction sensitive alors que le versant moteur était normal. La biopsie du nerf sural objectivait une dégénérescence segmentaire ancienne des petites fibres. La patiente décéda 4 mois après, dans un contexte d’état de mal convulsif et d’hyperthermie. Mots-clés : Neuropathie sensitive congénitale, Dakar SUMMARY Congenital sensory neuropathy is rare. We reported the first case diagnosed in Senegal. A 30- months-old girl who had a insensitivy to pain associated with foots’ ulcers and accidental trauma. Parents were consanguineous. Electroneuromyography showed a severe reduction of sensitive nerve conduction with normal motor conduction. Sural nerve biopsy showed a loss of small fibers. The girl dead 4 months after a convulsive status and hyperthermia. Key-words : congenital sensory neuropathy, Dakar INTRODUCTION Les neuropathies sensitives héréditaires sont un groupe d’affections génétiques qui touchent essentiellement les fibres sensitives du nerf périphérique et parfois le système nerveux autonome périphérique (1,2). Elles sont rares comparativement aux neuropathies héréditaires sensitivomotrices du type maladie de Charcot Marie Tooth. Nous rapportons le premier cas diagnostiqué au Sénégal. OBSERVATION Il s’agissait d’une fillette de 30 mois, enfant unique d’un couple consanguin (les parents étaient cousins germains). La grossesse et l’accouchement s’étaient normalement déroulés. La mère avait 2 surs vivantes et bien portantes et un frère décédé à l’age de 03 ans de cause inconnue. La fratrie du père (1 frère et 1 sur) était également bien portante. Il y’avait pas de tare familiale. L’examen clinique des parents était normal. Ils n’avaient rien remarqué d’anormal à la naissance et dans les premiers mois de vie. L’enfant s’était assis à un age normal, à 5-6 mois. La marche accusa du retard, vers 15 mois. EIle comprenait les ordres simples mais l’expression orale était pauvre, limitée à quelques mots familiers. Elle ne faisait pas de phrases. Depuis le début de la marche, la maman remarquait que sa fille se blessait constamment, sans en souffrir apparemment. Elle pouvait même marcher sur des braises, se piquer avec des objets tranchants sans la moindre réaction. L’examen physique ne mettait pas en évidence de déficit moteur. La peau était sèche, craquelée ; la patiente ne réagissait pas aux stimulis nociceptifs à l’éveil comme dans le sommeil. Elle ne réagissait pas au pincement et lorsqu’on la piquait avec une aiguille. Les réflexes ostéotendineux étaient abolis aux 4 membres. On notait par ailleurs, des troubles trophiques à type d’ulcération indolore du gros orteil droit et de nombreuses cicatrices sur les 2 pieds. La glycémie était de 0,79 g/l et le bilan rénal normal. L’étude des vitesses de conduction nerveuse montrait une sévère neuropathie sensitive axono-myélinique, prédominant aux membres inférieurs, les vitesses de conduction motrice étaient normales. A la biopsie, le muscle coloré à l’Hématoxilline Eosine ne présentait pas d’anomalie. Le nerf en coupes semi-fines colorées au bleu de toluidine montrait des fascicules riches en fibres myélinisées. Le teasing montrait de grosses fibres normales, de petites fibres présentant une dégénérescence segmentaire ancienne. DISCUSSION Les neuropathies périphériques de l’enfant sont généralement d’origine génétique et la neuropathie sensitive congénitale est une affection très rare. Elle représente 3% d’une série de l’Université de Sydney (1). Malgré l’absence d’autres cas familiaux, la consanguinité parentale, les caractères cliniques et électriques de la neuropathie, l’absence de trouble métabolique (diabète, insuffisance rénale) militent en faveur d’une neuropathie héréditaire de transmission autosomique récessive. Le cas de notre patiente s’apparente à la neuropathie sensitive héréditaire de type II ou ce sont principalement les fibres non myélinisées et les petites fibres qui sont réduites en nombre. Cette atteinte explique la symptomatologie clinique dominée par une atteinte de la sensibilité thermoalgésique et ses conséquences trophiques allant de lésions superficielles à des atteintes profondes plus graves. Le diagnostic est souvent tardif et ce sont habituellement les troubles trophiques qui attirent l’attention des parents et les amènent à consulter. Les vitesses de conduction sensitive sont effondrées alors que le versant moteur est normal. Cette sélectivité de l’atteinte sensitive est propre aux neuropathies héréditaires sensitives (1,3,4,5,6). Dans les autres neuropathies notamment métaboliques, les nerfs moteur et sensitif sont également concernés même si l’atteinte sensitive peut prédominer. Il s’y ajoute que la neuropathie s’intègre souvent dans un contexte d’atteinte multisystémiqe concernant le système nerveux central et d’autres organes. L’age de début aurait pu faire discuter le type IV mais dans ce dernier cas l’électromyogramme est normal (1, 2). Notre patiente est décédée dans un contexte d’état de mal convulsif et d’hyperthermie. La rapidité de survenue des signes et l’évolution fatale en quelques heures n’ont pas permis de faire les investigations paracliniques nécessaires en pareille circonstance afin d’asseoir un diagnostic précis. On sait cependant que ces enfants sont sujets à des hyperthermies malignes qui peuvent être fatales. La localisation et le gène en cause dans la neuropathie sensitive héréditaire II ne sont pas encore connus alors que des mutations génétiques sont mises en évidence dans les autres types (1). Aucun cas n’a été jusque là rapporté en Afrique mais les pathologies neuropédiatriques et en particulier les neuropathies périphériques sont mal connues. Les neuropathies périphériques sensitives sont rares, sauf dans les communautés juives Ashkenazi ou les avancées les plus significatives dans la recherche génétique ont eu lieu (1,6). L’affection n’est pas évolutive et des mesures d’hygiène et d’éducation suffisent à éviter les complications. Il faut avoir la hantise d’une atteinte osseuse chez ces patients dont la prise en charge est délicate et demander systématiquement des radiographies appropriées. La prévention est la seule alternative mais il est souvent difficile chez les enfants d’éviter les microtraumatismes dont les conséquences peuvent être gravissimes. La prise en charge est multidisciplinaire pouvant impliquer outre le neurologue, le dermatologue et parfois le chirurgien lorsque les lésions osseuses s’installent (5). CONCLUSION Le diagnostic des neuropathies sensitives chez l’enfant n’est pas aisé mais devant des troubles trophiques, il faudra y penser et faire les examens complémentaires nécessaires. Il faudra rechercher une consanguinité parentale et déterminer le mode de transmission par l’enquête familiale qui est essentielle dans l’approche diagnostique. Le diagnostic est d’autant plus important qu’il permet une prise en charge adaptée et précoce.  Figure 1

Le rapport récent de l’Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS, WHO)) sur « The public-health challenges of neurological disorders »mérite d’être salué, car il permettra de porter une attention particulière sur les affections neurologiques, considérées dans la plupart des pays sub-sahariens comme étant marginales. Toutefois, cette démarche suscite une remarque fondamentale. Le problème de l’accessibilité aux soins neurologiques est complexe car multifactoriel, impliquant plusieurs acteurs sur fond crucial de nécessaires allocations de ressources financières. En effet, à la question posée par le LANCET (1) Neurology in sub-saharian Africa – WHO cares ?, on peut répondre par une autre question : QUI PAYE ? WHO PAYS ? La focalisation de l’action neurologique à partir du village me paraît irréaliste. En effet, lorsque les indices diagnostiques auront été relevés au niveau local, le recours à un avis spécialisé sera nécessaire. Or, il existe une pénurie… mortelle de médecins et plus particulièrement de neurologues, 0.3 pour un million d’habitants. Il faudra ensuite réaliser des examens complémentaires ( EEG, EMG, CT-Scan, …), moyens diagnostiques d’accès exceptionnels et qui ont un coût.En dehors de la République d’Afrique du Sud, on ne compte que 3 IRM dans les hôpitaux publiques dans toute l’Afrique sub-saharienne, soit 600 millions d’habitants, c’est-à-dire la population de l’Europe et de la Russie réunie ! Le prix d’un examen CT – Scan est d’environ 100 $ et le budget par habitant est de 1$ par jour pour 90% de la population. Il faudra ensuite payer les médicaments quand on sait que presque la totalité de la population n’est pas couverte par une assurance-maladie. Who pays ? Des solutions de financement existent et il ne s’agit pas de mendicité. Les dépenses de santé par habitant s’élèvent en moyenne à 3100$ (11% du PIB) dans les pays riches. Elles ne représentent que 81 $ pour les pays en voie de développement (6% du PIB). Le rapport rédigé sous la direction de Jeffrey SACHS ( 2 ) à la demande de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS), Macroéconomie et santé : investir dans la santé pour le développement économique, 2001 est formel : une augmentation des moyens financiers de 72 milliards d’euros par an dans le domaine de la santé permettrait de dégager au moins 396 milliards de gains annuels au bout de quinze ans, tout en sauvant 8 millions de vies chaque année. Les engagements financiers peuvent apparaître très importants, mais le retour sur investissement – outre les vies sauvées – est considérable. Ce même rapport précise qu’environ 34 $ par personne et par an sont nécessaires pour couvrir les interventions essentielles des pays à faibles revenus : le VIH/Sida, le paludisme, la tuberculose, les pathologies maternelles et périnatales, les causes fréquentes de décès de l’enfant (rougeole, tétanos, diphtérie, infections respiratoires aiguës, les maladies diarrhéiques), la malnutrition, les autres infections prévenues par une vaccination, les maladies liées au tabac. La plus grande partie de cette somme devra être financée par le secteur public. The World Health Organisation (WHO) report on « The Public Health Challenges of Neurological Disorders » is particularly welcome as it draws attention to a real health problem, which is deemed marginal in most sub-Saharan countries. The problem of accessibility to neurological care is complex in this region, as it implicates several actors on a background of acute scarcity of human and financial resources. Indeed, as indicated at the end of the editorial, the query “Neurology in sub-Saharan Africa – WHO cares?”(1) must be coupled with another question: “WHO pays?” At this stage of development of sub Saharan Africa, it would seem totally unrealistic to focus neurological care at the village level. Any diagnosis of a neurological disorder requires further professional advice, and professional advice must be followed by specialised tests (EEC, EMG, CT-SCAN, MRI), which are usually very costly. Outside the Republic of South Africa, there are only 2 MRI in public hospitals (Nigeria, Zibabwe) in the whole of the sub-Saharan region. Moreover, as is well known, there is a scarcity of medical doctors, especially neurologists on the continent – 0.3 per million persons while the total African population is estimated at 600 million, which is equivalent to the combined population of Europe and Russia. The cost of a CT-SCAN is approximately $100 when 90% of the population live on $1 a day. To the costs of the professional advice and tests, one must add the costs of medication in the absence of any type of health insurance. WHO pays? Financial solutions do exist and they do not require begging for more loans. In the developed world, health spending per person is estimated at $3100, about 11% of GNP. In developing nations, this amount drops to $81 (6% of GNP). A report made for WHO by Jeffrey SACHS and al. (2) – “Macroeconomics and Health : investing in health for economic development” – states that, in the health sector, a rise in financial commitments of 72 billion euros annually would translate into a gain of 396 billion euros over 15 years, whilst saving 8 million lives each year. The report also estimates that an amount of $34 per person per year would be sufficient to cover the costs of basic health care in low income African countries, including HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, maternal pathologies and prenatal care, diseases causing infant mortality (chicken pox, tetanus, diphtheria, respiratory infections, water borne diseases), malnourishment, preventable diseases and tobacco related diseases. The major part of this financial contribution should and could be financed by the public sector. The recurrent clichés on the poor management of development aid, in particular by African countries, are not sustainable (3). A large part of external aid is well spent and has delivered spectacular results. In 1967, smallpox caused some 10 to 15 million deaths worldwide. Some thirteen years later, that disease had been eradicated thanks to the implementation of a special WHO programme. In 1988, there were some 350 000 polio cases. In 2003, only 784 cases of polio were recorded thanks to a 3 billion dollars control programme. This type of aid must be continued, and amplified, especially in the fight against the AIDS pandemic. For a maximum efficiency, action must be taken in partnership and directly on concrete projects such as scholarships, training, lectures, and equipment (4). Creativity is necessary in promoting such initiatives, for example, with the use of NTIC ( 4, 5). STROKE MORTALITY IN A TEACHING HOSPITAL IN SOUTH-WEST OF NIGERIAABSTRACT Stroke, a major cause of morbidity and mortality is on the increase and with increasing mortality. Our retrospective review of all stroke admissions from 1990 – 2000 show that cerebrovascular disease accounted for 3.6% (293/8144) of all medical admissions; has a case fatality rate of 45% with the majority (61%) occurring in the first week; mean age of stroke deaths was 62 years (SD +/- 13); and severe as well as uncontrolled hypertension is the most important risk factor. Community based programmes aimed at early detection and treatment of hypertension in addition to screening for those with high risk factors should be put in place. INTRODUCTION Stroke is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in black Africans, responsible for between 0.9 to 4% of total admissions to hospitals and 0.5 to 45% of neurological admissions1. Recent studies have shown stroke to top the list of admissions into the medical wards2. In Europe and North America there is a progressive decline in Stroke mortality rates from the 1950s to 1980s following which the rates have stabilized. In the MONICA study3, the case fatality ranged from 15-50% with an average of 30%. The highest case fatalities were in the Eastern European countries while the lowest occurred in the Nordic countries. In the United States, there has been a decrease in the case fatality of stroke from 15.7% in 1971 -82 to 11.7% in 1982-92, a change that has been attributed to decline in the incidence due to primary and secondary prevention and improved treatment. In a Nigerian community-based study the age-adjusted mortality rate of stroke is higher than that of the USA, most likely due to the increasing burden of hypertension and diabetes, lack of resources and limited access to medical treatment. PATIENTS AND METHODS We retrospectively reviewed the hospital records of all in-patients with clinical diagnosis of stroke admitted and managed in the neurology unit of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex (OAUTHC), Ile-Ife, Nigeria between 1990 and 2000. One hundred case files were available for review and the data obtained were analyzed using the statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 11.0. RESULTS Stroke admissions accounted for 3.6% (293/8144) of all medical admissions, and with a case fatality rate of 45% (range 28.8%-56.0%) Table 1. Of the 132 deaths, only 100 case records were available for review. The male to female ratio was 1.9:1. Stroke was uncommon below 40 years (6%) whereas more than half of the deaths (54%) occurred in the 6th and 7th decades. The majority of the deaths (61%) occurred within the first 7 days of admission. The most common risk factor for stroke was hypertension (78%), followed by diabetes mellitus (9%), and cardiac arrhythmia (4%). Majority (69%) had severe hypertension (JNC stage 2) at presentation. The mean systolic blood pressure among the stroke deaths was 170 (SD +/- 42), and the mean diastolic blood pressure was 106 (SD +/- 29). Factors contributing to mortality include septicaemia 52%, hypotension 12%, renal failure 5%, and recurrent strokes in 23%. DISCUSSION Stroke remains an important cause of hospital related deaths. Previous workers noted a rise in the frequency and mortality in Nigerian patients with stroke1. Stroke was responsible for 3.6% of medical admissions, similar to the findings of Osuntokun

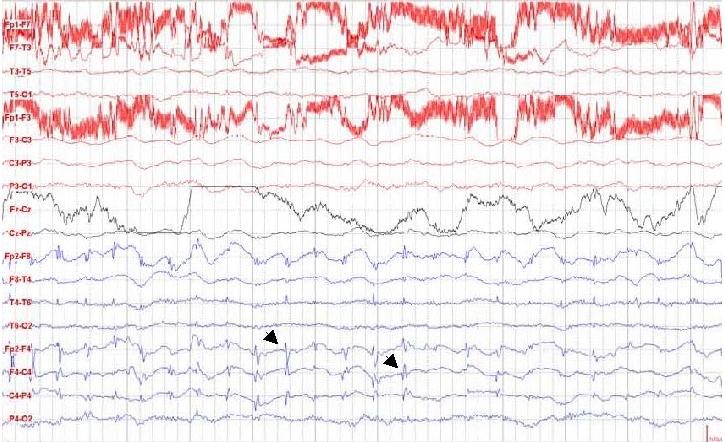

ABSTRACT Hypomelanosis of Ito (HI) is the third most common neurocutaneous disorder. HI is thought to be more common in non-white/pigmented population. However only one case seems to have been reported from Africa and no case has been reported from East or Central Africa. We describe a case of a 12 years old girl seen at our centre with hypo-pigmented whorls over most of her trunk and limbs following the lines of blaschko typical of HI. She had learning disability and musculo-skeletal anomalies. Key words: Hypomelanosis of Ito, Neurocutaneous disease. RESUME Hypomelanosis d’Ito (HI) est le tiers la plupart de désordre neurocutaneous commun. SALUT est pensé pour être plus commun dans la population de non-white/pigmented. De quelque manière que seulement un cas semble avoir été rapporté d’Afrique et aucun cas n’a été rapporté d’Afrique centrale est ou. Nous décrivons un cas d’une fille âgée de 12 ans vue à notre centre avec les spirales hypo-pigmentées plus de la plupart de son tronc et membres après les lignes du blaschko typiques du HI. Elle a eu l’incapacité d’étude et les anomalies musculo-squelettiques Mots clés : Hypomelanosis d’Ito, la maladie de Neurocutaneous. INTRODUCTION Hypomelanosis of Ito (HI) is thought to be the third most common neurocutaneous disorder after neurofibromatosis type1 and tuberous sclerosis. Recent literature suggests that this condition may be under reported. It is thought to be more common in people with pigmented skins, but there is only one case report from Africa. Whether this is due to low prevalence or under recognition and underreporting of this condition in the region remains unclear. CASE REPORT A 12-year-old girl who presented to Kilifi District Hospital on the Kenyan coast with a history of seizures and bizarre behaviour. “Fits” were described as episodes of suddenly falling down from undisturbed sitting position, which often recurred. These episodes were brief, followed by rapid and complete recovery within a minute. No post- ictal activity was reported. The bizarre behaviour was described as lack of sleep with the child remaining awake during the night, making unintelligible sounds and crying inconsolably. These complaints had been present for the last year. Past medical history revealed that the child had previously been hospitalised with a similar complaint. The pregnancy and birth history was uneventful. The child was born at home and at term. She is the fifth born. Developmental history revealed marked delay in achieving all her milestones: head control was not achieved till about the age of 7 months, the child did not sit till almost the age of 2 years, and took even longer to walk. This was achieved well passed the 5th birthday of the child. A sibling born two years following this child walked before her. Physiotherapy was commenced on account of delayed walking but was later discontinued. She is not toilet trained and has not acquired speech. No such illness has been seen in the family as a far as the guardian could recall and no one in the family suffers from epilepsy or any other familial disorder. Examination findings On clinical examination she did not appear wasted, however she weight 24.7kg (below 3rd percentile) for her age and sex. Her head circumference was 54.6cm (above 97th percentile for age and sex). She had hypo-pigmented whorls over most trunk and the limbs following the blaschko lines (Figure 1). These skin lesions according to the mother were present since when the child was about one year of age. The mother did not have these whorls and did not recall of any other relatives with similar skin features. The child had a contracture of the right ankle joint, which was held in fixed planter flexion. Examination of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems revealed no abnormalities. The child appeared to have global developmental delay, could not follow commands and showed little evidence of social interaction. She lacked expressive speech and only made guttural noises. The vision appeared normal in that the child would grasp an object placed in front of her, but the visual acuity could not be assessed. It was also not possible to fully assess the auditory function, however free field-audio testing suggested that the child could hear. She had exaggerated knee jerk reflexes and bilateral ankle clonus. The plantar reflex was equivocal bilaterally. She could stand with support using mainly the left leg but could not walk. There were no anomalies noted on the head and spine. The rest of the examination was normal. Diagnostic evaluation A full blood count and electrolytes were normal. An electro encephalograph (EEG) revealed slow waves distributed globally with frontal spikes (Figure 2). Computerized Tomography scan of the brain showed normal cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, normal ventricular system and no space-occupying lesion. DISCUSSION Ito first described Hypomelanosis of Ito (HI) in 1952. The characteristic feature are the cutaneous zone of hypo-pigmentation following the lines of blaschko with varied clinical presentation. The most common complications reported are developmental delay and epilepsy. Infantile spasms in the first year of life and autistic behaviour as also been documented. Other reported anomalies include ocular, musculoskeletal, oral and urogenital malformations. No universally accepted diagnostic criteria for HI exist. One suggestion was that the criteria should include dermatological lesions plus non-dermatological abnormalities especially of the central nervous system (CNS) and skeletal or chromosomal abnormalities. These criteria exclude cases with only dermatological manifestations. Skin lesions suggestive of HI have been described without or with variable degree of systemic manifestation and this complicates the establishment of a diagnostic criteria. Numerous complications have been associated with this condition involving the central nervous system, ocular, musculoskeletal oral alteration and urogenital malformation. Many chromosomal abnormalities have been reported in association with HI and the presence of two genetically different cell lines is thought to be a common factor. Though the condition is thought to be more frequent in dark skinned races very few cases have been reported in Africa. We could only identify only one case from West Africa from a Medline search , but none from East or Central Africa. This may be due to a low prevalence or underreporting, but since this condition is easily recognizable in Africans, more attempts should be made to report such cases.  Figure 1: Hypopigmented whorls on anterior trunk.  Figure 2: EEG showing spikes in the frontal area. (See arrows)

Articles récents

Commentaires récents

Archives

CatégoriesMéta |

© 2002-2018 African Journal of Neurological Sciences.

All rights reserved. Terms of use.

Tous droits réservés. Termes d'Utilisation.

ISSN: 1992-2647