|

|

|

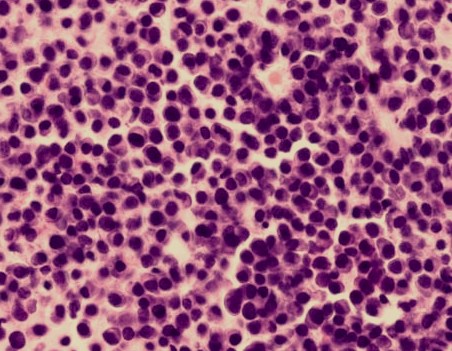

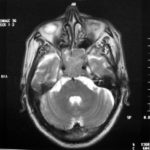

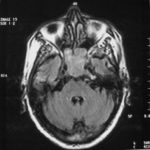

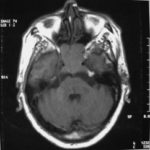

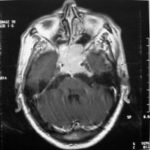

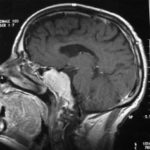

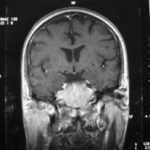

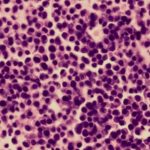

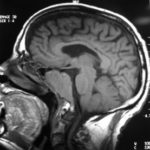

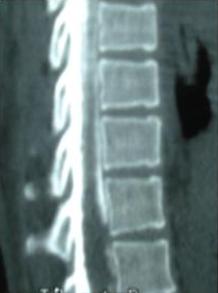

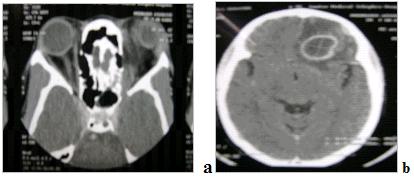

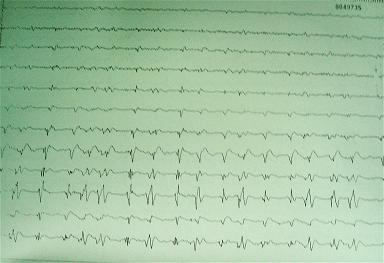

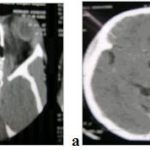

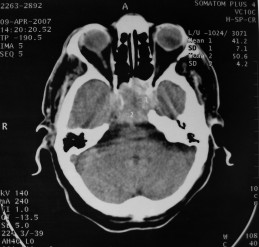

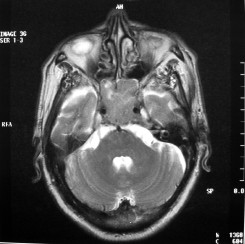

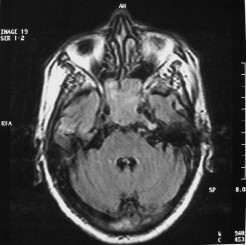

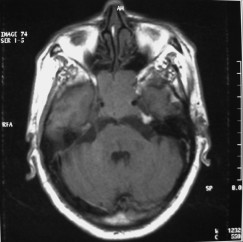

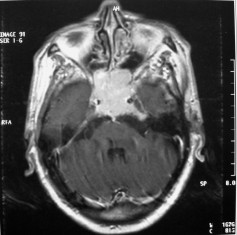

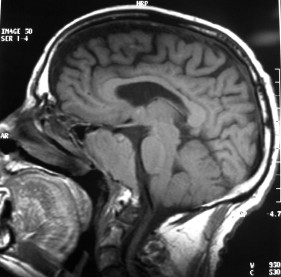

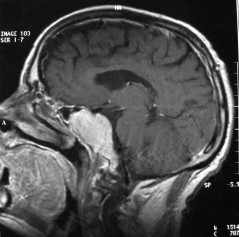

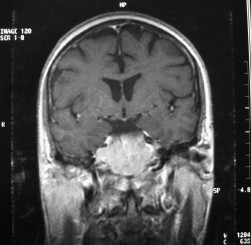

There are several areas in child health in which early detection measures are likely to make a critical impact upon the health and education of the child or at least diminishing the impact of developmental disabilities. Autism is one of these areas. It would be very interesting to know if any country in Africa -east, west. south and north- has managed to solve the problem of provision of services for children with learning difficulties and behavioral problems. Identifying autism and its complications has had limitations….the interventions themselves are costly particularly in the manpower required to perform the services. Perhaps it is because Paediatricians spend so much time diagnosing common childhood problems-e.g.gastroenteritis,epilepsy and other common medical conditions that can nowadays be diagnosed and managed by general practitioners-that they become rather shortsighted and fail to see the wider problem of behavioral difficulties in children. It is the time now to consider behavioral problems in children as a wide problem. This “hidden handicap” is a most serious disability as it frustrates communities and otherwise normal families, often going unsuspected and unrecognized even by doctors. In order to consider what are the best practical measures to help the children and their families and to ensure that these children receives the attention and the care. We as Paediatricians must put more efforts to identify those children and decide what we can usefully do to help the many-not only the few. The greatest problems are with the rural underprivileged majority rather than with the privileged urban minority None of us as professionals can deny that this is a major problem but what is the most effective action? In ideal, and wealthy, situations the children with behavioral difficulties can be helped; a few by medications, many by the care of parents, teachers and the community. Children with moderate to severe behavioral difficulties attend special schools which are expensive education in any country of the world, but are the only path for the child to realize his or her potential. The priorities for these children are early detection and early intervention to prevent if possible any disability. Between 1930 and 1975 the world population increased by 2 billions; it doubled. Today the total is 5 billions and rising. At least two third of the total live in the so called “underdeveloped or developing” countries of which Africans are included. With this increase in the population and the associated problems subsequent to this, behavioural difficulties have become a major problem that needs attention and solutions. In many countries circumstances make these priorities though no less valid. either impossible or too expensive to attain. Special education is rarely started early enough and even if, against all difficulties, a child does gain a place in the school, the majority only starts at 6 or 7 years, by which time they are “fixed observers” Parent’s guidance is an additional task to be added to the duties-by no means light and easy-of the primary health care workers. What is Autism? Autism is a lifelong developmental disability that prevents children making contact with other people. It can profoundly affect the way children communicate, behave and limit their ability to interact and relate to others in a meaningful way, develop friendships, show signs of affection, appreciate cuddles or understand other people’s feelings. Because the severity and variation of symptoms, the disorder is often referred to as Autistic Spectrum Disorder or ASD rather than autistic continuum disorder. Spectrum in now preferable; it suggests a collection of related but varied conditions whereas the continuum suggests a smooth transition from one end to the other, which is not the case with autistic disorder1. The International Classification of Diseases 10th edition 2 and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 4th edition 3 do not recognize the term ASD but refer to pervasive developmental disorders. Autism affects more children than cancer, cystic fibrosis and multiple sclerosis combined. One in every 250 babies has autistic spectrum disorder. The condition is four to five times more common in boys than in girls. Essential Features: Impaired social communication and delayed speech and language are the developmental areas that cause most concern to parents of young children with autism. The process of language acquisition in children with autism does not follow a normal pattern. In the early stages, echoed words and phrases are evident; later this echolalia will be replaced by learnt language that can be out of context. Some children become very verbal, yet fail to learn the rules about dialogue.4 Impaired social interaction is another diagnostic criterion for autism. Children with autism tend to talk AT rather than with people and are unaware of others feelings and points of view. Typically, such children have difficulty attending to anything outside their areas of interest.5 Impairment in areas of imagination is wide. They lack creativity; while some children may show skill with constructional toys such as Lego, others are capable of functional play yet they fail to develop these activities in an imaginative way. There is repetitive quality about their play and it never seems to lead anywhere.5 ASSOCIATED FEATURES In addition to the primary characteristics that define the autism syndrome, there are associated features that are frequently present as well. Although these features are not essential for a diagnosis of autism, they are often observed in this group and can have important implications for the management of children with autism. Several cognitive abnormalities are frequently observed in young children with autism: distractibility, poor organizational ability, difficulties with abstraction, and a strong focus on details. Mental retardation is an additional cognitive disability in about 70% of children with autism and there is often an uneven cognitive profile with some skills being strong while other aspect of cognitive functioning are quite limited. Abnormalities of posture and motor behaviour include stereotypes like arm flapping and grimacing, abnormal gaits, and odd posturing with hands. Under-and over- responsively to sensory impact is common; some children with autism resist being touched while others ignore sensations like pain. Many children with autism are fascinated by specific sounds or taste. Abnormalities of drinking, eating, and sleeping behaviour and fluctuations of mood are also frequently observed. Eating, drinking, and sleeping problems often resolve themselves by adolescence but can be troublesome prior to then. Eating a limited variety of food and staying up all night are among the most difficult of the ongoing problems parents face with young children with autism. Lability of mood is also common and is observed in several variations; giggling or weeping for no apparent reason, absence of emotional responses or reaction to danger, excessive fearfulness, or generalized anxiety.1 Self-injurious behaviour, such as head banging and finger or hand biting, are the most extreme and frightening of the behaviour accompanying autism. These occur in less than 10% of the population but can be the most difficult to control or remediate. In their most extreme form these behaviours requiring hospitalisation.1 DECLARATION OF THE PROBLEM Although age of onset is no longer a diagnostic criterion, autism begins early in life (almost always before 3 and rarely before 5). Most children with autism show signs of the disability from birth though there are some cases where early normal development is followed by a deterioration of social, cognitive, behaviour and communication skills. In these instances deterioration following normal language development is usually the first indication of the problem.6 Recent evidence that the prevalence of diagnosed ASD may be increasing and that early diagnosis and intervention are likely associated with better long term outcomes has made it imperative that Paediatricians increase their fund of knowledge regarding the disorder. Changes in diagnostic criteria and classification systems may at least in part have contributed to the reported increased rates of ASD in epidemiological research Earlier studies (Fombonne et al) estimated the prevalence of autism to be 13 in 10 000 persons. However, Bird et al studying a large cohort of 9-10-years-old children, estimated the total prevalence of ASD to be 116.1 per 10 000, that is, approximately 1% of the child population. Currently, there are no data available for African population; however if the conservative rates apply. Paediatricians can now expect to care for at least 1 child with autism. The apparent increase may represent a combination of several factors, including changing criteria with inclusion of milder forms in the spectrum of autism, a higher public and professional recognition of the disorder, and a true rise in prevalence.6 Although a group of researchers in UK has hypothesized that the administration of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine was associated with an increased risk of ASD, this hypothesis has not been substantiated by more in-depth research .In addition, it is imperative that health professionals and the public realize that congenital rubella can cause autism and that measles and mumps can cause significant disability, including encephalitis.7 The Paediatrician is faced with the challenging task of suspecting an ASD diagnosis as early as possible and implementing a timely plan to achieve the best outcome for the child and the family. In neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD, where the complex pattern of skills and difficulties may show a variable pattern across setting and over time, the paediatrician’s role within the care pathway is crucial, especially at the time of initial diagnosis and at review of developmental progress and in contributing with colleagues to the identification of onset of new disorders.8 Early diagnosis of ASD is challenging in the context of primary care visits because there is no pathognomonic sign or laboratory test to detect it. Thus, the physician must take the diagnosis on the basis of the presence or absence of a group of symptoms. Because ASD is a phenomenological rather than an etiologic disorder, making the diagnosis more challenging. Paediatrician must rely on parent report, clinical judgment, and the ability to recognize criteria-based behaviour, that define ASD.Families are calling on their Paediatricians to guide them through the tunnel of behavioural, educational, psychological, and alternative treatment option available to them. Research has demonstrated that recurrence rate for isolated ASD in subsequent siblings ranges from 3% to 7% which make early diagnosis is important to ensure timely genetic counselling before the conception of subsequent siblings.9 What can we do to help? It is possible to take a negative and passive view and say “There are far worse problems in many countries in Africa-starvation, housing, sanitation, water supply and war- so why divert efforts?” Or “There are other problems that can often be helped by simple procedures, and we don’t see much behaviour difficulties around” There are indeed, many other terrible problems in Africa but behavioural difficulties are so severe disability that every professionals in the field of paediatrics must positively contribute at least through advocacy so as to highlight and cry for help for the resolution of some of the problems that are responsible for the injustices in the distribution of medical care for children in Africa. Authors’ affiliations H Darrat, Al-Khadra Teaching Hospital, Department of Paediatrics, Tripoli, Libya A Zeglam, Department of Paediatrics, Tripoli University, Associate Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health, and Consultant Neurodevelopment Paediatrician, Al-Khadra Teaching Hospital, Tripoli, Libya Correspondence to: Dr. Adel Zeglam, PO Box 82809, Tripoli, Libya zeglama[at]yahoo.com MYELOME MULTIPLE REVELE PAR UNE INVASION SPHENOÏDALE. A PROPOS D’UN CASRESUME Le plasmocytome envahit rarement la base du crâne. Qu’il soit solitaire ou multiple, la présentation clinique est dominée par une neuropathie progressive de plusieurs paires crâniennes et plus spécialement un syndrome du sinus caverneux. Le diagnostic étiologie est habituellement difficile à partir des données de l’imagerie. Les auteurs rapportent l’observation d’un patient de 83 ans présentant un syndrome du sinus caverneux isolé. Les investigations neuroradiologiques révélaient une lésion destructrice des régions sphénoïdale, éthmoïdale, sellaire et pétroclivale. Une biopsie sphénoïdale par voie rhinoséptale a permis de diagnostiquer un plasmocytome. Un bilan d’extension confirma la présence d’un myélome multiple. Les données de neuroimagerie du plasmocytome de la base du crâne sont loin d’être spécifiques. Cependant, cette entité devra être évoquée devant toute lésion invasive de la région sphénoïdale. Mots Clés: IRM, Myélome multiple, Plasmocytome, Sinus sphénoïdal, TDM. SUMMARY Plasmocytoma rarely involves the skull base. Being solitary or multiple, a progressive course of multiple cranial neuropathies was the most common presentation especially cavernous sinus syndrome. Making diagnosis from the imaging findings was usually difficult. The authors report an 83-old-man with an isolated cavernous sinus syndrome. Neuroradiological investigation revealed destructive lesion of sphenoid, ethmoid, sellar and petroclival areas. A transsphenoidal biopsy showed features of a plamocytoma and a subsequent workup confirmed the presence of multiple myeloma. The neuroimaging features of skull base plasmocytoma are nonspecific. However, this entity should be suggested in the differential diagnosis of invasive sphenoid process. Keywords: CT-scan, MRI, Multiple myeloma, Sphenoid sinus, Plasmocytoma. INTRODUCTION Les plasmocytomes sont des tumeurs malignes essentiellement osseuses. La région cervico-céphalique est rarement intéressée ; qu’ils soient primitifs ou secondaires, il s’agit essentiellement de plasmocytomes extramédullaires sous-muqueux dans la filière aéro-digestive supérieure (6). L’envahissement des sinus paranasaux est rare (18). L’extension à la base du crâne demeure exceptionnelle, moins d’une trentaine de cas ont été décrits dans la littérature simulant de nombreuses autres lésions néoplasiques essentiellement intrasellaires (1- 6, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18). Nous rapportons le cas d’un plasmocytome invasif du sinus sphénoïdal révélant un myélome multiple (MM). Nous attacherons une attention particulière aux caractéristiques de la neuroimagerie TDM et IRM de cette entité rare. OBSERVATION Ce patient de 83 ans, ancien tabagique, nous a été adressé pour la prise en charge d’une lésion sphénoïdale. Le malade présentait depuis deux mois des céphalées en casque, récemment associées à une diplopie. Il n’existait pas d’altération de l’état général. L’examen neurologique trouvait une paralysie complète du VI droit associée à une hypoesthésie superficielle du V1 et V2 homolatéraux. L’examen clinique était par ailleurs strictement normal. Le scanner cérébral trouvait une volumineuse masse isodense totosphénoïdale, légèrement étendue aux deux sinus caverneux, à la selle turcique et au clivus, fortement rehaussée par le produit de contraste (Figures 1). Les reconstructions en coupes sagittales et coronales mettaient en évidence une érosion du clivus, du plancher de la selle turcique et des cellules éthmoïdales postérieures. L’IRM confirmait l’existence d’une volumineuse lésion sphénoïdale tissulaire à extension intra et latéraosellaire vers les deux sinus caverneux (Figures 2, 3). Sur les séquences pondérées T1, la lésion était en isosignal, rehaussée après injection de Gadolinium, mais présentait un signal différent de celui de la glande hypophysaire (Figures 3A, 3B). Le bilan endocrinien n’était pas perturbé. Après un bilan préanesthésique, une biopsie chirurgicale par voie rhinoseptale a permis de poser le diagnostic de plasmocytome. Les suites opératoires sont restées simples sans aggravation neurologique. L’examen anatomopathologique définitif après immunomarquage confirmait le diagnostic de plasmocytome. L’électrophorèse des proteïnes sériques mettait en évidence un pic monoclonal kappa à 7.98 g/l (taux d’IgA à 19g/l). L’examen des urines ne trouvait pas de proteïnurie de type Bence-Johns. Les radiographies simples du rachis, de la voûte du crâne et du bassin ce sont avérées normales. Cependant, la scintigraphie osseuse mettait en évidence des zones d’hyperfixation au niveau de l’épaule droite et de l’arc postérieur de la 7° côte droite. Le patient a été adressé en oncologie pour une chimiothérapie adjuvante et une radiothérapie locale après que le diagnostic de myélome multiple a été signé (dissémination myélomateuse au myélogramme). DISCUSSION L’incidence des plasmocytomes représente moins de 1% de toutes les tumeurs cervico-céphaliques (11, 13, 18). L’atteinte de la base du crâne est particulièrement rare puisque moins d’une trentaine de cas ont été rapportés dans la littérature dont une dizaine d’observations de plasmocytomes solitaires (2-6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18). Si dans ces deniers cas il s’agit d’adulte d’âge jeune (entre 30 et 50 ans), l’âge moyen de découverte dans les MM est de 60 ans, notre patient est probablement le cas le plus âgé jamais recensé dans la littérature (83 ans) après celui de Nofsinger (79 ans) (11). La diversité et l’importance des structures environnantes du sinus sphénoïdal expliquent le large spectre de la présentation clinique. Néanmoins, les symptômes les plus fréquents sont les céphalées et l’atteinte des paires crâniennes plus particulièrement les nerfs oculomoteurs (2, 4, 15, 18). D’autres part, le plasmocytome est responsable de moins de 4% des lésions invasives du sinus caverneux (16). Les diagnostics différentiels des lésions tumorales du sinus sphénoïdal sont extrêmement variés (1, 5, 10, 14, 15, 18). Dans une série de 132 cas de lésions isolées du sinus sphénoïdal, Lawson (9) retrouvait dans 21% des cas un mucocèle, un carcinome primitif dans 10%, une tumeur à point de départ pituitaire dans 3%, une métastase dans 2% et seuls trois cas de plasmocytomes (2%). Le reste des lésions correspondait à des maladies inflammatoires et infectieuses. Les investigations neuroradiologiques aussi poussaient soit-elles ne permettent pas un diagnostic pré-opératoire de certitude. Cependant, il existerait certains aspects pouvant orienter le diagnostic étiologique. L’érosion osseuse n’est pas un bon critère pour différencier le plasmocytome de lésions comme les métastases ou les lymphomes qui peuvent se comporter comme des lésions expansives, soufflant la corticale osseuse, aussi bien que comme des lésions agressives responsables de véritables lésions lytiques. Le carcinome primitif du sinus sphénoïdal entraîne généralement des lésions lytiques aboutissant à une perte de définition des contours du sinus sphénoïdal d’aspect assez caractéristique. L’adénome hypophysaire ayant son origine dans la selle turcique détruit systématiquement le plancher sellaire lorsqu’il existe une extension intrassphénoïdale, l’absence d’un tel aspect nous a permis d’éliminer ce diagnostic (1, 15). Le mucocèle dont la croissance est lente entraîne un remodelage du sinus sphénoïdal mais pas de lésions lytiques. Si le signal tumoral et la prise de Gadolinium en IRM ne sont pas spécifiques d’une étiologie donnée, l’origine extrapituitaire de la lésion peut être affirmée comme chez notre patient. La prise de contraste massive chez notre malade ainsi que l’absence de l’hypersignal en T2 a permis d’éliminer le diagnostic de mucocèle. Cependant, l’absence de calcifications relativement fréquentes dans les tumeurs du sinus sphénoïdal constitue un argument allant contre l’hypothèse d’un chondrosarcome qui présente souvent des calcifications en motte ou curviligne. L’histogénèse des plasmocytomes des sinus paranasaux est encore mal élucidée, s’agirait-il d’une extension à la base du crâne à point de départ sous-muqueux, sphénoïdal ou endocrânien ? A côté des difficultés du diagnostic histologique, facilement levées par la pratique des immunomarquages, le principal problème que pose la découverte d’une tumeur plasmocytaire du sphénoïde est de l’ordre nosologique. S’agit-il de la manifestation inaugurale d’un myélome multiple avec généralisation d’emblée ou différée de quelques mois et dont la moyenne de survie ne dépasse pas 18 mois ? S’agit-il, au contraire, d’un plasmocytome solitaire authentique dont le pronostic est radicalement différent ? (5, 15). Dans tout les cas, une surveillance clinique, biologique et radiologique demeure nécessaire puisque plus de 85% des cas de plasmocytomes solitaires développerait un authentique myélome multiple (7). A signaler que les patients présentant une atteinte de la base du crâne auraient plus de risque de développer un myélome multiple que ceux présentant une lésion sous-muqueuse nasopharyngée (18). La radiothérapie est le traitement de choix pour les plasmocytomes solitaires, elle sera ciblée sur le corps du sphénoïde. Un complément de chimiothérapie est nécessaire en cas de myélome multiple (3). Certains auteurs ont montré que l’évolution, lorsqu’elle n’est pas favorable pour les lésions primitives (plasmocytomes solitaires), correspond le plus souvent à une évolution de la maladie à distance du foyer initial (myélome multiple) et préconise donc dés le stade de début une chimiothérapie adjuvante à la radiothérapie (2, 18). CONCLUSION Les plasmocytomes de la base du crâne révélant un myélome multiple représentent une entité rare. Cependant, qu’ils soient solitaires ou multiples, le plasmocytome doit être considéré dans le diagnostic différentiel devant toute lésion invasive du sinus sphénoïdal. La présentation clinique est aspécifique. Les renseignements apportés par les investigations TDM sur l’atteinte osseuse et par l’IRM sur le signal tumorale et la prise de contraste permettent, la plupart du temps, d’orienter le diagnostic. Cependant, une certitude histologique doit être obtenue. L’exérèse tumorale complète n’a jamais été validée en terme de contrôle tumoral et de survie et par conséquent, n’est pas recommandée. Enfin, même si la radiothérapie permet d’obtenir la plupart du temps un contrôle tumoral local satisfaisant pour les formes solitaires, il nous semble justifié d’y associer systématiquement une chimiothérapie adjuvante afin de limiter l’évolution à distance de la maladie.  Figures 1A  Figures 1B  Figures 1C Figures 1. TDM cérébrale en coupes axiales avant (A), après injection du produit de contraste (B) et en fenêtre osseuse (C). Volumineuse masse tissulaire sphénoïdale étendue aux sinus caverneux, à la selle turcique, aux cellules éthmoïdales postérieures et à la région pétroclivale. Notez l’importance de la prise de contraste et de la destruction osseuse. Figures 1. Axial CT-scan before (A), after contraste administration (B) and bone Window (C). Soft tissue mass with associated bony destruction involving the sphenoid, posterior ethmoid cells and bilateral petroclival areas.  Figures 2A  Figures 2B  Figures 2C  Figures 2D Figures 2. IRM cérébrale en coupes axiales en SpT2 (A), FLAIR (B), avant (C) et après injection de Gadolinium (D). La tumeur de signal tissulaire s’étend vers les deux sinus caverneux avec refoulement des deux carotides internes. Figures 2. Axial MRI on SpT2 (A), FLAIR sequence (B), noncontrast SpT1 (C) and postcontrast SpT1 images (D). Tumor of the sphenoid sinus extending to the cavernous sinus with displacement of the internal carotid arteries.  Figures 3A  Figures 3B  Figures 3C Figures 3. IRM cérébrale en séquences pondérées T1 avant (A) et après injection de Gadolinium (B) montrant la différence de signal entre le processus expansif et la glande hypophysaire. Coupe coronale après injection de Gadolinium (C). La lésion sphénoïdale prend fortement le produit de contraste avec envahissement bilatéral des sinus caverneux. Figures 3. Sagittal MRI on SpT1 before (A) and after Gadolinium administration (B) showing difference of signal between the lesion and the pituitary gland. Coronal view after Gadolinium administration (C). The sphenoidal process is illustrated with massive contrast enhancement and bilateral involvement of the cavernous sinus.

EXCITING COLLABORATION BETWEEN IBRO, EFNS AND WFN OPENS UP IN AFRICA! Over the past couple of years IBRO has been developing collaborative links with major neurological federations to promote clinical neurosciences in Africa. In this respect, IBRO has made strong ties with the World Federation of Neurology (WFN) and more recently the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS). The ARC and SONA have also renewed their links with the Pan African Association of Neurological Sciences (PAANS; www.ajns.paans.org), who will hold their biennial conference in Yaoundé, Cameroon this November, 2008. Since the highly successful, WFN-IBRO symposium (promoted by WHO) in April 2007 in Nairobi, the WFN has established an Africa Committee (AC) to develop neurology training in the continent. The WFN AC, chaired by one of the original members of IBRO ARC Prof Gallo Diop, was officially launched at a meeting in March this year in Stellenbosch, convened by WFN President Johan Aarli (Norway) and Secretary-General Raad Shakir (UK). In June (26-28, 2008) another milestone was reached. The EFNS in co-operation with IBRO and WFN lead the first Teaching course (TC) in Dakar, Senegal. This excellent joint venture, to continue in future years, was chaired and organized by Professors Gallo Diop, MM Ndiaye (Senegal), P Ndiaye (Senegal), J-M Vallat (France) and J De Reuck (President EFNS, Belgium) along with several colleagues from the EFNS, WFN, IBRO and University of Dakar. The TC was launched by the Dean of the Faculty (C Boye) during the Opening Ceremony, at which representatives of each of the sponsoring organisations (J De Rueck, EFNS; R Shakir, WFN and R Kalaria, IBRO) and local WHO representative (A Felipe) welcomed all and thanked the organisers. The TC in Dakar was featured under two themes: Peripheral Neuropathies and Dementia. Didactic lectures on epidemiology, symptoms, treatment and management were delivered in the morning and cases relating to themes were discussed in the afternoons. Over 100 neurology trainees and specialists attended the course held at the Medical Faculty site of the University. Among the TC attendees there were 10 IBRO alumni. The international teaching faculty with expertise in their own right comprised G Avode (Benin), J De Reuck (Belgium), J Dumas (France), M Gonce (Belgium), R Gouider (Tunisia), E Grunitzky (Togo), R Hughes (UK), R Kalaria (UK-Kenya), B Kouassi (Cote d’Ivore), MM Ndiaye (Senegal), A Njamnshi (Cameroon), M Rossor (UK), R Shakir (UK), A Thiam (Senegal), J-M Vallat (France) and D Voduek (Slovenia). On the last day a highly interactive session several practical issues and difficulties concerning neurology practice in the bush’ were discussed. Representatives of WFN, PAANS and Pan Arab Union of Neurological Societies (PAUNS) also reassured the attendees they are available to help African neurology practice, teaching and research. IBRO Secretary-General Marina Bentivoglio also provided a brief but important overview of the work of IBRO. Ms. E Sipido (Italy), I Mueller (Austria) and M Soda (Senegal) were invaluable in providing logistical help. IBRO ARC looks forward to future collaborative activities with the EFNS and WFN in Africa. There are plans already in hand for the second TC in Anglophone sub-Saharan Africa in 2009. Taking part in this nouvelle initiative in Africa has been a wonderful privilege for us. We take this opportunity to thank colleagues from all sides (IBRO, EFNS and WFN) for their encouragement and assistance. This first joint TC event with EFNS was made possible by the generous contributions from UNESCO and IBRO. Pictures: 1) The attendees of the 1st joint EFNS-WFN-IBRO Teaching course in Dakar 2) IBRO alumni with Marina Bentivoglio, Gallo Diop and Raj Kalaria at the EFNS-IBRO TC in Dakar

Le dossier complet doit être adressé avant le 1 octobre 2008 au responsable de la Sous-commission Francophonie & Coopération de la LFCE : Dr. Guy FARNARIER – Sous-commission Francophonie & Coopération de la LFCE guy.farnarier[at]ap-hm.fr Informations sur la Bourse Francophone de Recherche et d’Action en Epileptologie COURS INTERNATIONAL FRANCOPHONE DE NEUROCHIRURGIE DE DAKARLe troisième Cours International Francophone de Neurochirurgie de Dakar s’est déroulé du 18 au 19 Février, sous les auspices de la Société de Neurochirurgie de Langue Francaise (SNCLF), l’association Pan-Africaine des Sciences neurologiques (PAANS),l’Association des Sociétés de Neurochirurgie Africaines (ANSA). Les tumeurs cérébrales en constituaient le thème. Une forte délégation de la SNCLF a honoré de sa présence ce cours : Cinquante deux participants africains ont assisté à la formation, représentant seize nationalités. Le séminaire a débuté par une mise au point sur les aspects anatomo-pathologiques des tumeurs cérébrale. L’étude anatomique de la substance blanche a par la suite permis de mieux comprendre le mode de propagation des gliomes et partant les principes de leur exérèse. L’étude de la vascularisation des méningiomes, les impératifs de la préservation du réseau veineux lors de la chirurgie ont également été abordés. En pratique courante, les indications chirurgicales des métastases cérébrales constituent une réelle difficulté et ont été passées en revue. L’anatomie chirurgicale du lobe temporal, les tumeurs hypophysaires, et les crâniopharyngiomes ont fait l’objet d’une riche discussion. L’équipe d’anesthésie de Dakar a décrit les possibilités de prise en charge des tumeurs cérébrales. De fructueux échanges ont ponctué les présentations consacrées à la neurochirurgie pédiatrique (les pays africains sont caractérisées par l’extrême jeunesse de leur population), les tumeurs de l’angle ponto-cérébelleux, les tumeurs pinéales. Après deux jours particulièrement studieux, une ’ fenêtre thérapeutique » a été consacré à la visite de l’ile de Gorée, notamment de la maison des esclaves. Les thèmes des prochains cours seront consacrés à la pathologie vasculaire et fonctionnelle. L’équipe de Dakar tient à remercier l’ensemble des encadreurs, la SNCLF, la PAANS et l’ANSA. Prof Codé Ba

Articles récents

Commentaires récents

Archives

CatégoriesMéta |

© 2002-2018 African Journal of Neurological Sciences.

All rights reserved. Terms of use.

Tous droits réservés. Termes d'Utilisation.

ISSN: 1992-2647